“If Santa Claus was a woman I always say she’d be Merle Foster,” Gordon Sinclair, the legendary Canadian journalist and broadcaster, told readers of his Radio column in the Toronto Daily Star, in 1952.

Like the bearded elf with the toy shop at the North Pole, Foster, a popular Toronto sculptor, was a “maker,” Sinclair reasoned. “Ask her to make anything from a moving model of the Noronic fire to the ride of the Valkyries in miniature and it’s done,” he said.

By then, Foster had been a household name in Toronto for more than three decades, known for her gargoyles and other architectural decoration, monumental works, portrait busts, public fountains, garden statuary, and small pieces such as sport trophies and bookends.

In fact, “maker” was a job description that had been applied to Foster in often-effusive newspaper and magazine profiles since her career began, in the early nineteen-twenties. But what Sinclair didn’t mention was possibly the best reason to consider Foster a female Santa Claus: the annual Christmas parties she gave for ten years for the children—street urchins, really—who haunted her studio and served as her models.

Her studio—located initially on Walton Street, eventually moving to Church and then Grosvenor during the twenties and early thirties—was also known among local children as a “make shop.”

“What does she make? ” one uninitiated child once asked another, a regular visitor to Foster’s studio.

“Jus’ everythin’,” the boy answered breathlessly.

They didn’t know what Sinclair knew: that although Foster specialized in clay modelling at the Ontario College of Art (as it was known when she finished her studies there, in 1918), she was also a plasterer, carpenter, toolmaker, tinsmith, electrician, and designer, her sculptural work crossing media, notably to papier mâché. Such disciplines weren’t on the O.C.A. curriculum of the early twentieth century, so Foster acquired her skills through a succession of small jobs with a potter, a plasterer, and a commercial engraver, among others.

So while Merle Foster’s “make shop” did not produce toys, it must have seemed as magical as Santa’s workshop to the children who visited. Not only was it full of fantastical creations, including figures for the T. Eaton Company’s annual Santa Claus Parade, but there was also clay to play with, and biscuits were always on offer.

There was also the undeniable appeal of Foster herself. Born Muriel Aileen, in 1897, “Merle” was a childhood nickname she kept into adulthood, “because no one knows whether I am a girl or a boy,” she once said, “which has its advantages in business.”

That may have been the only time she uttered the word “business.” Until she was well into her thirties, newspaper stories and magazine profiles invariably referred to Foster as being “not much more than a little girl,” calling her “Toronto’s girl sculptor.” Her zaftig figure, “jolly” demeanour (as it was inevitably described), “trilling” voice, and self-deprecation must have been irresistible to the neighbourhood children, to whom Foster must have seemed like a big kid herself. She sometimes denied she was an artist, calling herself instead “just a mud-slinger” who “made mud pies for a living.”

Her accounts were left to her manager—her younger sister, Florence, known as “Pory.” Foster’s aversion to business may seem strange for someone whose work was predominantly commercial sculpture, but the division of labour—Merle looked after the art, Pory took care of the accounts—seemed to suit each woman’s talents and temperament.

“When I took hold of things, Merle insisted that art was not to be—could not be—commercialized,” Pory said. “She was humiliated at the thought of such a thing, but I immediately started a filing system and filed away her humiliation with numerous other things.”

“See that figger over there wit’ the muffler an’ cap,” asked a neighbourhood boy, pointing out a sculpture to a friend who lived nearby as they looked through the Fosters’ window. “Dat’s me sister, Rosie.” In addition to modelling, “Me and Rosie run lotsa errants for her,” the boy bragged. He was quoted, in dialect, in Quality Street magazine, in 1926.

A writer for Maclean’s (or “MacLean’s,” as it was spelled at the time) was on hand one morning in 1923 when another boy popped his head in the door. “Don’t you want a model this morning, Miss? ” he asked, and showed no disappointment when Foster replied, “I wonder if you would go get your brother.” In fact, as the reporter noted, “The boy turned from the door for a moment and winked at a lad close by and in a twinkling the required brother was at his side.”

Although Foster paid her models, the spurned fellow cheerfully called his brother, no doubt because he had been a beneficiary of her annual Christmas generosity.

The neighbourhood was St. John’s Ward, known simply as “the Ward,” a notorious area of urban squalor bounded by Yonge Street, University Avenue, College Street, and Queen. It was home to recent immigrants—until the late nineteen-twenties, mostly Jews from eastern Europe as well as Italians and Chinese. (No wonder the Fosters’ studio was called “a spot of enchantment to the children of the Ward” year-round, especially at Christmas—the predominantly Jewish guests notwithstanding.)

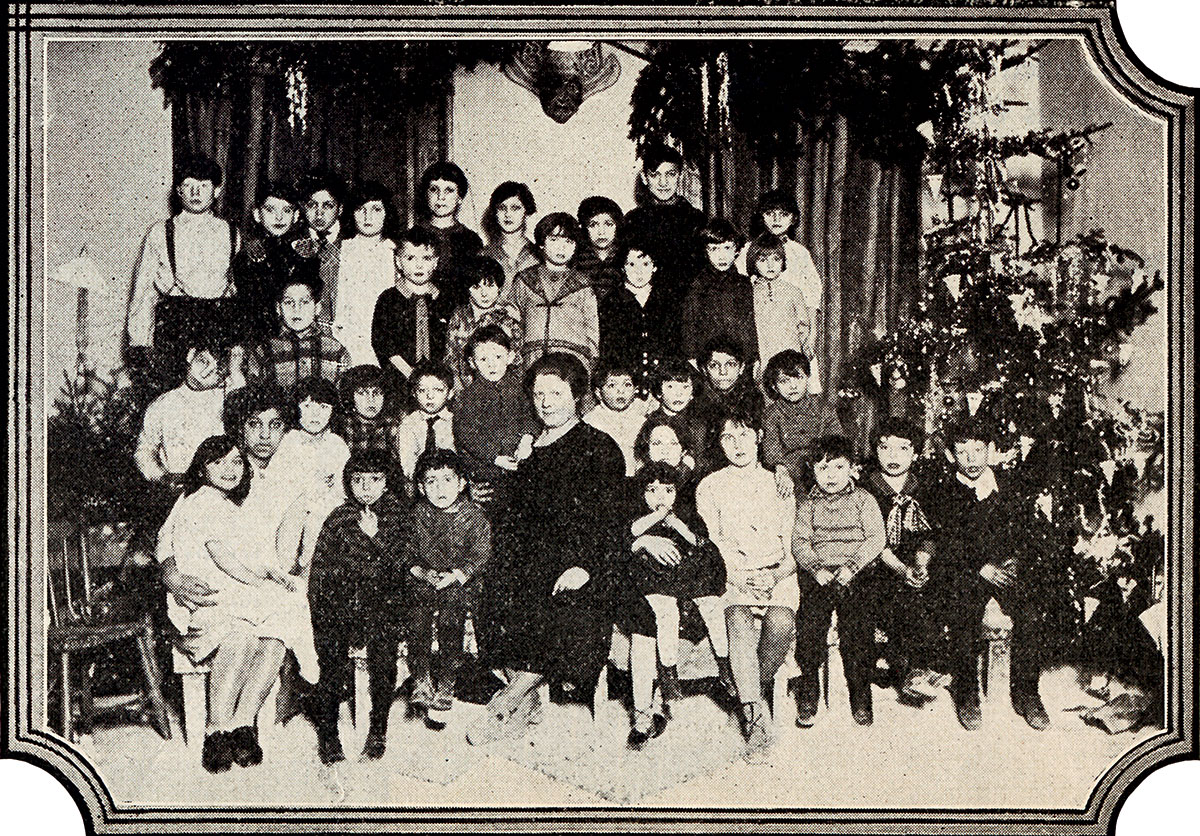

Foster’s parties—known at the time as “Christmas trees”—began in 1922, when she invited nine of her models to her decorated studio for food and gifts. She later expanded the guest list by asking the postman for names of other children in the area who he thought would have “little pleasure” during the festive season. In time, the numbers grew to thirty, fifty, and just short of seventy by the time of the last party, in 1931.

“I have no choice in the matter,” Foster said. “I simply set the day.”

For the first party, the gifts came from her own childhood toy box. By the second year, her toy box was empty and the number of guests had increased, so Foster turned to friends for donations. One of her more highly placed friends was Justin Cork, a co-founder of the Loblaws grocery chain, who provided hundreds of dollars’ worth of oranges and candy over the years. Toronto newspapers and other local publications also obliged by printing calls for toys and other gifts.

“Yesterday found boxes of candy for each child, oranges, sample bottles of sauces, sample packages of powder and toilet accessories for the small girls, 20 pounds of nuts, quantities of animal biscuits, numbers of dolls, all gifts from friends,” the Star reported of the 1927 party. “Games and the distribution of gifts occupied the afternoon, which began at three o’clock and still waxed strong at seven. The children brought their musical instruments, their banjos and violins, and entertained Miss Foster and her sister and their friends with their quaint music. Many of them danced and gave comic exhibitions of the black bottom.”

The next year, Chatelaine held up Foster’s annual party as a shining example of how an individual could give a “Christmas tree,” calling hers a “success that has evolved into a triumph from a very small beginning.”

“I’m just so grateful to the people who send me things and help me to keep this party going,” Foster said in 1930. “I’d hate to give it up.”

But the following year’s party was to be the last. On New Year’s Eve, 1932, the Star carried the news: “Toys and provisions have been rolling in all week to Merle Foster, the sculptress, the aftermath of her annual holiday party given for the children of the ‘ward’ who used to model for her when she lived there. This year, living in York Mills, she did not give the party but contributions poured in just the same. She had no difficulty in disposing of them, however, and they went to many deserving and appreciative folk.”

Foster’s Grosvenor Street studio had been expropriated in the development of Women’s College Hospital, and she had moved to the northern Toronto suburb—too far for the children to travel.

But other events, global and personal, also interfered with Foster’s ability to sponsor a party. She estimated that she lost ten thousand dollars’ worth of business during the Great Depression, and recalled 1933 in particular as a year when she “just got by.”

In 1930, Merle and Pory, two single women, found themselves the guardians of an infant girl named Barbara. In later interviews, Foster variously referred to her as an adopted daughter, a sister, and a niece—but surviving family members have confirmed that Barbara was Pory’s illegitimate daughter.

Throughout the Depression, Foster continued to be a “maker”—memorializing outings with Barbara in little paintings and sketches, and taking whatever work she could find, including creating headstones for Canada’s first pet cemetery, located in Aurora, Ontario.

Foster’s fortunes turned during the Second World War, when she took a job as the director of personnel for Victory Aircraft. The regular income must have been especially welcome because, by that time, she was supporting her parents, as well as Pory, Barbara, and herself.

Although the Victory job was full-time, she maintained as much sculpture work as she could get—including at least one commission she earned with the help of one of her former Ward friends.

When they were children, Lillian Pearlstein and her sister had modelled for Foster.

“One of [the sisters] married Mr. Sam Shopsowitz of Shopsy fame,” a magazine noted, mid-century. “Today, atop his [Canadian National] Exhibition stand there’s a larger than life size model of Shopsy, executed by Merle Foster who has been remembered all these years by the little model who became Mrs. Shopsy.”

After the war, Foster resumed “making” her living largely through her art, until she died, in obscurity, in 1986, the day before her eighty-ninth birthday. Foster had been a celebrity for six decades, known for her high-profile architectural commissions, virtually non-stop presence at the C.N.E., and contributions to parades and ice shows, as well as her child welfare work.

Today, most of her buildings have been demolished, the archives of the organizations she worked for have virtually no record of her, and the children whose lives she touched have grown up, grown old, and passed on, leaving almost no one to remember her.

“Ars longa, vita brevis”—the aphorism by the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates is usually interpreted as “Art is long, life is short.” Art goes on though the artist dies.

It’s actually only the start of a longer aphorism that has a somewhat different message: that learning an art (medicine, in this case) is a lifelong process.

But the shorter version and more simplistic interpretation of the saying may still be true—although the story of Merle Foster turns it on its head.