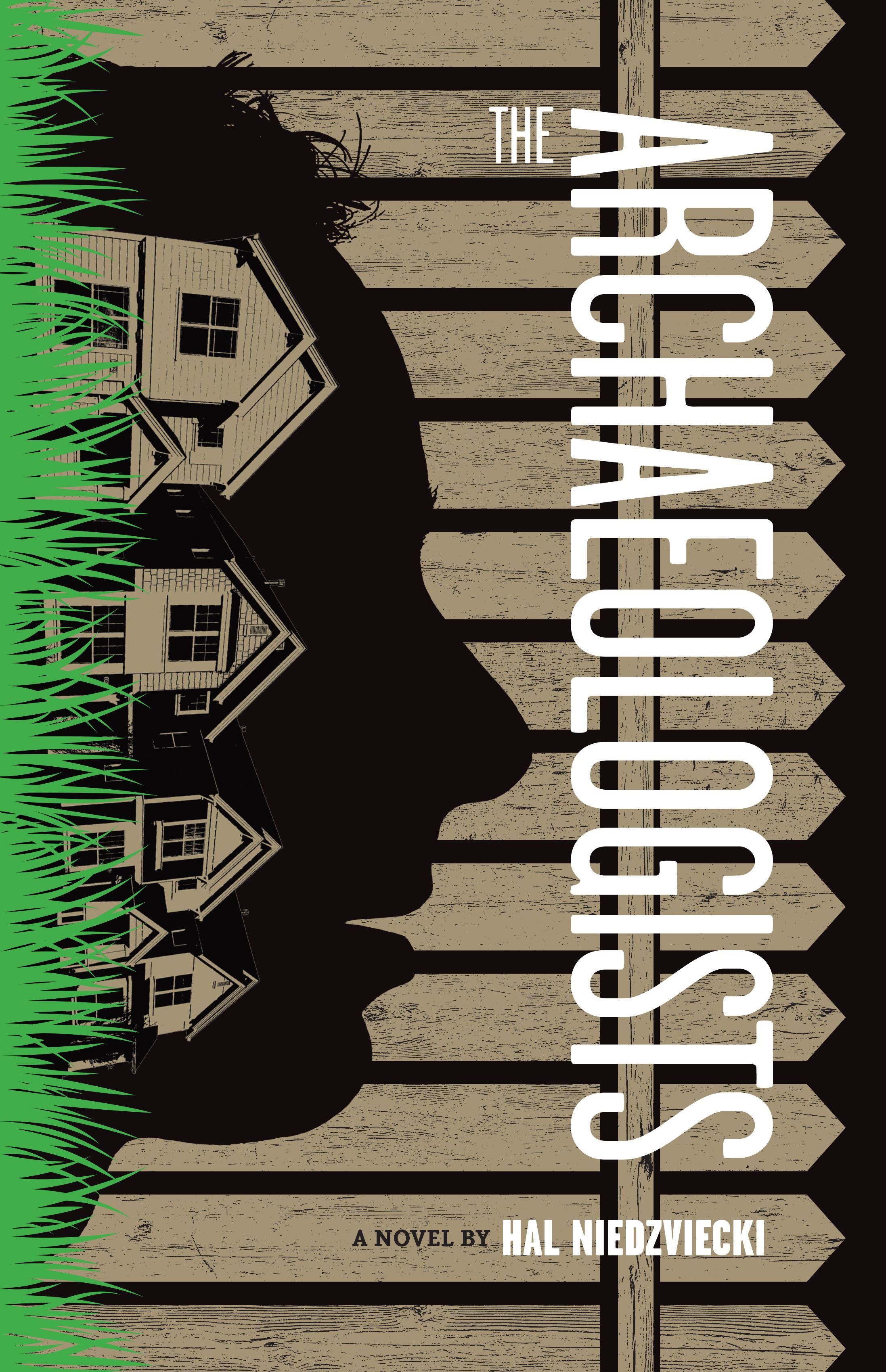

This chapter is part of the ongoing serialization of The Archaeologists, the new novel by Hal Niedzviecki, to be published by ARP Books in fall, 2016. The Archaeologists is being serialized in its entirety from April to October, with chapters appearing on a rotating basis on the Web sites of five magazines. View the schedule with links to previous/upcoming chapters, and find out more about the book.

The Wississauga campus is the satellite branch of the downtown university June attended not all that long ago. It’s a seventies-style jumble of long, low concrete buildings. June wanders the paved paths that connect them, occasionally stopping to consult the map of the campus she printed before driving over. Students bustle past hurriedly in purposeful groups. Exams soon, June thinks. She suddenly feels nostalgic for something as simple and straightforward as a final exam. The students, bright-eyed, thrive on manufactured, self-perpetuated urgency. June moves slowly, her muscles pulsing under her skin. She’s wearing a windbreaker over a sweatshirt. Her jeans are streaked with mud and dirt and her hair is pulled back into a ponytail. Unintentionally, she fits in. Just another clueless student in dirty jeans heading aimlessly into the future with all the vigour she can muster. June checks her map.

She’s looking for the Cartwright Centre for the Arts and Sciences. Cartwright. She’s heard the name before. He was the mayor, right? One of the founding fathers of Wississauga. Or Walletville. Or whatever you call it. Also has a wing named after him at the hospital. Probably owned that starch plant too, June thinks. The one Rose’s husband slaved away in for practically his entire life.

The Cartwrights were a rich family from England, but the students swirling in and out of the centre seem anything but. June pushes open the door of the building and stops just inside to get her bearings. Robes, veils, turbans, and burkas mix and match with ubiquitous T-shirts, jeans, and varsity sweats. What would Rose say about this? June’s own inner city campus had been so much more—white, she thinks. Not that there’s anything wrong with it. It’s just that she’d always thought of Wississauga as a Cartwright sort of place. And the city was where all the…mixing went on.

Not that there’s anything wrong with it.

A giggling group of girls flow around June in a wave.

C’mon, one of them says, her voice ringing in June’s ear. We’ll be late!

June checks her watch. The class she’s looking for will be over in five minutes. Anthropology 303Y: History and Settlement in the Lower Wallet River Valley. Professor Nordstrom. Classroom 201. June finds the stairs, takes them two at a time. She likes the feeling of moving so deliberately. She walks into the class just as the Professor is wrapping up. Next week, he says loudly, we’re reviewing the major themes for the final. The students, thirty or so, pack up their notebooks, murmur to each other. June stands pressed against the back of a lecture hall that could easily seat eighty. Tell your classmates, the Professor yells. Perhaps some of them will be good enough to join us for a change. The students file out, talking loudly, eyeballing June, obviously not chastened on behalf of their truant fellow scholars. Professor Nordstrom packs his notes in an absentminded, semi-agitated way. He looks young to June, a slightly pudgy fellow with pink Nordic skin, thin blond hair, and wire-rimmed glasses.

June approaches, stands near the lectern.

Professor Nordstrom looks up, startled.

Ah, oh. I thought you were all—he considers June. Are you one of my students?

No, Professor, I’m—

Good. Good then. Because I’ve never seen you before. And I usually like it if my students attend at least one of my lectures per semester. The Professor laughs sardonically, exposing small white teeth.

Nordstrom speaks with a Nordic lilt and formal British construction.

No, I’m not a student I’m . . .

June thought he’d be from here. Someone teaching local history.

Professor Nordstrom hefts his briefcase. Well then. Come along to my office and we will get you sorted out.

Professor Nordstrom’s office is an unimpressive cubbyhole lined with books. A small window lets in a rectangle of greying afternoon. The Professor has to suck in his gut to squeeze behind his desk. June wants to turn away from the sight. Nordstrom lands heavily in his chair, sighs, and jovially pats the pot of his soft protruding belly.

Now then, Miss . . .

June. June Littlewell.

Miss Littlewell, then.

June nods.

What can I do for you today?

June fidgets with her fingers. Well I, I used to go to—I graduated from the downtown campus . . .

Nordstrom winces visibly at the mention of the downtown campus.

Not that, June says quickly, there’s anything wrong with—I mean, I live in Wississauga now and I’m sure if I had . . . I mean, it’s so much more . . . diverse, here, than I—

Er yes, Nordstrom brightens. They are the only ones who take anything seriously at all. Hard workers. Fascinating, really, when you consider that they would be the last people you would expect to have an interest in local history. Nordstrom laughs, as if he’s made some kind of joke. June reddens.

It’s quite something, Nordstrom says reassuringly. It really is quite something.

Yes, well, I was—I mean, I graduated eight years ago, from downtown, so things were—

Eight years ago! You look so young, my dear. Now let me guess. You are thinking of, perhaps, graduate work in the field? You do not have your heart set on it, I hope. Because it is, well, I would not want to discourage you, but you would have to be exceptionally dedicated and talented because, you see, opportunities are limited. Everybody wants adventure, everybody wants to search for, er, buried treasure. So it is a bit of a crowded field, right now, and for the, er, foreseeable future.

No, Professor, I’m not here to find out about graduate school.

Then, er, Miss Littlewell, why are you here today?

You see . . . I recently moved into a house just above the . . . river. And I feel like, I’ve been wondering about the . . . history.

So you want to take the course next year? We would be delighted to have you, naturally. Campus policy is very clear on the issue of, er, community relations. Continuing education students from the area are always welcome. You’ll have to enrol with the Mature Students office if you can forgive the bother. And of course, Professor Nordstrom continues, looking at June in a greedy way that leaves her suddenly uncomfortable, you must also put out of your mind the inappropriate, er, nomenclature, after all, you’re hardly what we think of, that is, er, it’s just that word: mature.

Professor, June says, conspicuously placing her wedding ring hand on top of a closed file folder. I, yes, thank you, I would like to take the course. It sounds very interesting . . . but what I’m wondering, Professor, what I really need to know is . . .

What is it? What does she really need to know? The clock ticks. Someone is talking on the phone in the next office over. Professor Nordstrom looks on curiously, his eyes beady, his lips shiny, his cheeks rosy, his thinning hair plastered to his pink forehead.

Who were the first? June blurts. Who were the first people to live in . . . She’s blushing again. Not, she pushes on, like the first . . . white people. I mean . . . the really first people . . . here.

Nordstrom looks at her with bewildered alarm. He’s not used to dealing with the public, he’s done a few interviews with that young reporter on community television regarding the occasional find of a spear tip. Happy to do it. Good for the university, public profile and what not, increases his overall exposure. Of course he’s not one of those who craves the attention, isn’t about to get caught up in junk science and outrageous speculation just so he can make the newspapers. Slow and steady, that’s his motto. His latest paper is sure to get published in the prestigious Stockholm Journal of Anthropology, which will lead to further advancement in his career, funding, postings, so on and so forth. The more he gets what he deserves the less he’ll find himself having to deal with this kind of…he doesn’t even really know what to call it…

Professor?

Nordstrom does a little quiver, emerges from his flustered reverie. But that is . . . er . . . that is an interesting question!

It is?

Of course it is. I mean, do you realize . . . well, obviously you do not realize, but let us just say that if I knew the answer to that, well, I would not exactly be sitting . . . er, I would be, that is . . . well, Nordstrom giggles awkwardly.

But you must know something.

Nordstrom sighs. Surprisingly little, Miss Littlewell. Surprisingly little.

June resists the sudden urge to reach over, grab the man by the collar protruding from his argyle sweater and shake him.

Please, Professor, she says through clenched teeth.

Well . . . er . . . I . . . really . . . er . . . He stops and rescans her, as if a bulb had been suddenly turned on, revealing her in a totally different light. Well then, Miss Littlewell, as you might have observed, office hour continues and much to my surprise no paying customers seem to be lining up at my door. Ah ha ha. So why, as they say, the hell not? I will endeavour to—what do they call it? Give you the, er, “cheat sheet” version? How will that be? The Professor’s gaze roves over her, lingers on the folds of her sweatshirt. Now, you want to know who the first were? The very first people to occupy the Lower Wallet River Region?

Yes, I—

Well at least your inquiries are ambitious. You see, what you are really asking is, perhaps, the most contentious debate in archaeology today. Who were the first people to enter into the Americas? How did they get here? Do you understand what I am saying, Miss Littlewell?

Yes. Of course.

Good. Good. Some believe that the Americas were populated by Asian nomads who followed herds of, oh, er, woolly mammoth or beefalo—ah ha, a joke, Miss Littlewell—but, er, some such type mammaloid, across the frozen landmass that is now the Bering Strait waterway separating, er, Siberia from the continental North America, from, er, Alaska. That, at least, is the accepted theory. This, of course, all would have had to take place during the ice age around, oh, twelve thousand years ago.

Twelve thousand years, June repeats, without exactly meaning to.

Yes, well, it is quite a number, nothing, of course, as impressive as the finds in Africa, homo erectus and all that, half-a-million years old, those are. At any rate, okay then, it freezes over, makes for a convenient passage, and a bunch of chaps wander over from Siberia and the next thing you know you have some fifteen hundred different tribes from the Arctic to, er, Brazil.

So, June says uncertainly, the first—I mean, the first people who ever, who lived in . . . Wississauga . . . came from . . . Russia?

Ha, very humorous, an interesting way of putting it. But they were not sporting fur hats and leaving a trail of vodka bottles for us to follow, I am afraid. You see, it is—well, er, where to start?—first of all Miss Littlewell, there was no Russia. There were no countries at all. We’re talking about a pre-modern era. Before the dawn, so to speak, of civilization. They were primitives, for lack of a more appropriate word, though of course these days we have to be, er, aware of the, er, cultural sensitivities and of course do what we can to express ourselves, er, appropriately. So these people that we are talking about, they had no countries. No writing. No towns or cities. A rudimentary language at best, the bare beginnings of culture.

But—

And if the first visitors to our, er, little suburb were, indeed, descendants of the nomads who wandered over across the Bering Strait, then we can safely assume that it would have taken them many, many generations for that migration to take place. After all, it’s a long way to walk, from the Alaskan hinterlands to Wississauga. Professor Nordstrom chortles clumsily as if he’d just told a dirty joke.

June stares at him. He’s like some kind of awkward boy. She thought he’d be serious. Tell her something real.

As if sensing her annoyance, Nordstrom shifts tone: Have you ever been to the Arctic?

June shakes her head.

Of course not. But I did not want to assume. I have been several times. The quiet is so intense it feels like the loudest sound imaginable. A vast, wide-open space that defies imagination. Pre-history is like that, as well. It is, you see, er, the study of a time before time as we know it, er, existed. It is a topic so vast and imponderable it is like—here, give me your hand.

Professor Nordstrom eagerly grabs June’s right hand in both of his. A soft digit probes her palm.

You see, Miss Littlewell, the lines of the palm intersecting. Contradictory. Intricate. Who put them there? What do they mean? They have found, my colleagues, sites in New Mexico and South America, that clearly predate the earlier sites discovered in the North. Sites that seem to even predate the ice age. So where did those people come from? Well it’s really quite impossible to know. Did they boat over from Africa? From Australia? Maybe your Russians are really Laplanders from Greenland? You see Miss Littlewell, we are dealing with an, er, extremely complicated question. It is a maze. We have been following the lines of a palm.

His finger, tracing delicately, perversely.

Your hand is so rough, he says.

I’ve been dig—working—in the backyard. Gardening.

You have been digging Miss Littlewell? What have you been digging? Did you find something that might be of interest to—us—here? Is that why you have come to see me? Because I’d be happy to, er, work with you, to include you in my . . . research.

Professor Nordstrom’s eyes acquire a different glint.

You know, he continues, there have been, er, several significant sites found, here, in the Wallet River valley. In construction sites, mostly, but that doesn’t preclude a significant find in, say, a backyard. Sadly we haven’t been able to study the findings closely. They are carted away by my colleagues in Natives Studies two buildings over, Miss Littlewell. Two buildings and a whole world apart. Yes, they are the ones who make the decisions around here, and I am afraid that these days the findings—precious, very precious evidence, Miss Littlewell—are quickly covered up again. Well, it is all done for the right, er, reasons, of course. In fact it’s really, er, quite something to see, all kinds of ceremonies and whatnots performed, of course, yes, they still have their customs. But, still, Miss Littlewell, such a shame to have to . . . wel . . . sometimes, it is possible to do just a quick survey, of the, er, findings, before—So! Nordstrom gives her hand an encouraging squeeze. You say you live over by the river?

No—I mean, yes, but I—

Because the native peoples of the area date back some eight thousand years. Of course there are very few, er, findings from that time. Most of the materials we have of the pre-contact life of the native peoples come from the last, oh, 600 years.

Eight thousand years?

You did find something, didn’t you, Miss Littlewell?

She pulls her hand out of his grip.

June wanders aimlessly through the campus. The sun peers out from behind distant clouds. Yellow grass borders pavement paths. It’s late afternoon. She should head home and cook dinner. She’s hot under the windbreaker. The low long concrete buildings sit awkwardly in the sun. They’re built for winter, squat forts meant to keep out cold dark days, not let in the spring light. She’s not going back to school. She might be dressed like them. But that’s about it. To that Nordstrom it’s just numbers and facts and statistics. He doesn’t get it. He doesn’t know that it’s—real. A gaggle of co-eds scamper past. The late afternoon early spring sun warms her pale face. Nordstrom made it sound like they were animals. Savages. Wandering around in the ice and snow thousands and thousands of years ago. But June knows something else, something else about—

He—

He was—

A building juts over her. June stops walking and looks up. The footpath dead-ends at a larger square of a building, the only structure that seems to have more than three floors. The library, June thinks. Why didn’t she just go to the library? She feels like an idiot. There’s no curse, Rose. No ghosts, no scary spirits. It’s all just science, what can be explained, what can’t be explained . . . yet. She’s gotten out of the habit of reading. Norm’s not much of a reader. He likes books about famous inventors and rags-to-riches entrepreneurs. Even then he prefers the TV version. Sum it up, he says, when the telemarketers get him on the phone. He calls his little office the library, but it’s more like a museum—a mausoleum, June thinks. A repository for objects fixed in time; the way things were, the way her husband likes to think they are. A wall of framed diplomas hangs over an imposing cherry wood desk. The desk, vast plane of glazed wood, sits almost empty except for a few strategically placed gold fountain pens, journals of dental science, a blank pristine yellow legal pad, and, finally, a sealed box of Cuban cigars, probably a gift from a grateful patient—Norm doesn’t smoke, bad for the lungs, not to mention the dent it would put in what he likes to call the old pocketbook.

June ponders the dark entrance to the library. Students bustle by, hurrying to get things done before the end of the day. Her muscles are stiff, each movement of her arms and legs a conscious effort. It seems dark. The sun dropping. Already? Is it that late? Wind gusts down the path. It’s suddenly colder. Cold out here. June wishes it was summer, feels a hunger for heat, in the summer she’ll travel, have Norm take her somewhere, somewhere tropical, balmy. No. What she really wants are the summers of her childhood: fire flies and the waft of freshly cut grass, the buzz of mosquitoes, the sun gentle on her face, her mother calling her in for dinner. Suddenly she aches for it. Her body bruised with longing.

June wills herself up the steps.

And on into the stacks, tight pressed walls of books dwarfing thin aisles just big enough for one person to move through them. June walks aimlessly, scanning spines. She finds herself in Physics, then Chemistry, rows of over-sized texts with equations in the titles. She keeps moving. History, she thinks. Or Anthropology. Maybe there’s a whole Native section. But she stops at Biology. A row of seriously thick books with names like Complete Human Anatomy. Complete. She likes the sound of that. Here are answers. Facts. Cold hard truths. What was she thinking? Rose, that horrible Professor Nordstrom, they don’t have any answers.

June pulls out the book. She needs both hands, rough palms against a thick, grainy cover. Her muscles are taut, and under them, the bones, flexible yet rigid. Bones.

She takes the book over to one of the little study tables jammed in here and there against the walls of the library. She puts the book on the desk. She opens it to the contents. Description and Detail of the Human Skeleton. June finds the section. There it is. Figure 2.1. She traces the bones with a red, ragged finger. She’s thinking about him now, imagining him. He’s squat and powerful. Legs, June thinks. Strong, short legs. Tibia, she reads. Fibula, patella, femur. June says the words out loud, whispers them, hears them fade out and disappear in the dusty empty library. They were here first, Rose hisses with a note of disgust. Crazy old lady with her ghosts and curses. It’s not like that, June thinks. So what’s it like? June peers back down at the diagram. Bones. She has to start somewhere. She’ll figure out the parts, put them in order. Then she’ll see. What they are. What they want to be.

This was an excerpt from The Archaeologists, to be published by ARP books in fall, 2016.