When they let me go, I didn’t know the language of the place where I was, nor did I know the name of the place. And the shoes I was wearing: black canvas sneakers with white laces. I didn’t know where they had come from.

My knees and ankles ached, because I’d been kneeling for so long. It felt good to walk, even if I didn’t know where I was walking. A woman wearing a white raincoat and a red kerchief came walking toward me, then walked right by me. Soon it happened again, but this time with a young man. These were other people.

Amid the rows of houses that lined the road was what appeared to be a store. It had signs outside and a smiling chipmunk cut out of thin wood. Before they let me go, they’d stuffed some paper money into my pocket, so I walked into the store. I said to the man at the counter that I was thirsty. He had a very thin black moustache and no eyebrows. It was like he had taken his eyebrows and stuck them under his nose. He frowned when I spoke.

I drew one of the bills from my pocket with one hand and pointed to my mouth with the other. I licked my lips.

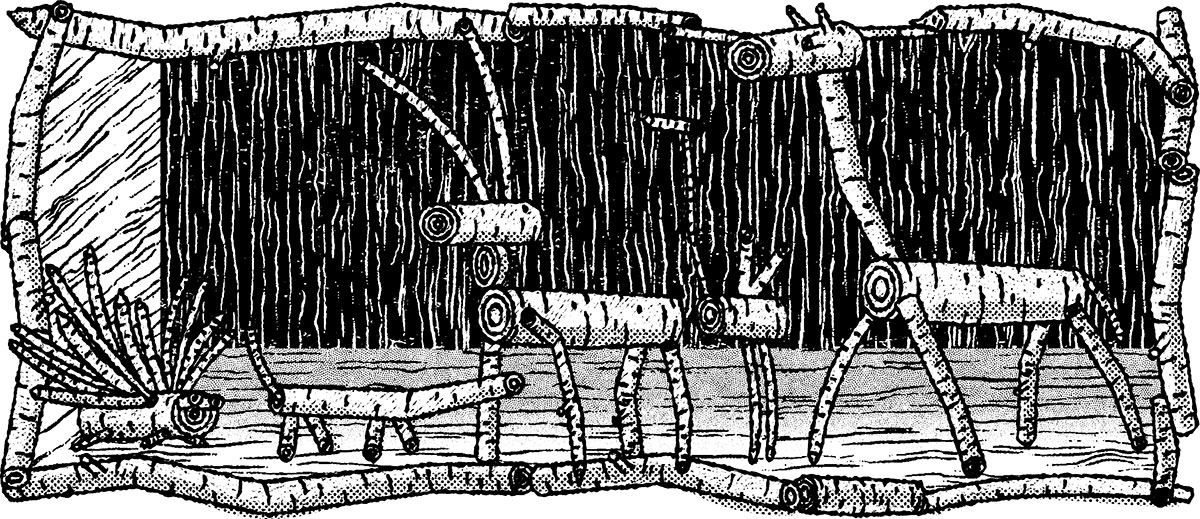

The man swept his own hand through the air in front of him, and I looked around his store. The shelves were lined with animals constructed out of twigs. I saw giraffes and gazelles and flamingos and porcupines, but I didn’t see any water.

The man stepped around the counter and took my arm. He led me back out to the street and pointed toward the crest of a hill. With his slender hand flat, he made the motion of a fish leaping and said something I didn’t understand. Then he turned his hand as if to slice something, and slalomed it through the air between us. This was a fish swimming. Then he held an invisible ladle to his mouth, puckered his lips, and slurped.

Over the hill there was a river. I could drink from the river.

On my way up the hill, I passed dozens more houses but I saw no more people. The people were all in their houses. Before I knelt in the dark, I had been in a house. I wanted to knock on their doors, knock on the doors of these other people who were inside, and tell them they weren’t safe.

As I approached the top of the hill, I could see dark clouds hovering above the road, which was by now made only of dirt. My black canvas sneakers were turning grey. It wasn’t long before I stepped into those frenetic clouds, and I realized they were swarms of aphids. They burrowed into my hair and ricocheted off my cheeks. They played in my eyelashes and among the follicles in my nostrils. I could only squint now, because the aphids wanted to swim on the surfaces of my eyeballs, but down the other side of the hill I could see a river that wound and curved like a child’s crayon scribble on a piece of paper.

When I’d had enough of playing, I stepped from the clouds of aphids and felt the pain in my ankles again as I walked slowly downhill. At the side of the river, I tried to crouch, but couldn’t bend my knees. The water was cool and clear, the river bed adorned with colourful round pebbles.

I puckered my lips and sucked as hard as I could, but I couldn’t draw the water up to my mouth. It was down there. I was up here. I stood beside the river. The sun never went down.