The rattle of a faltering engine drew June to the front of the house. She pushed aside the curtain and peered out. Bud, a balding man in his early forties, was rummaging through the trunk of his rusted tan ’67 Biscayne. His large belly was barely contained by a white cotton T-shirt with a peeling yellow decal of a leering happy face, a black tongue protruding out of one corner of its mouth. A few inches of soft white flesh covered in matted black hair was visible where the T-shirt ended and a pair of tightly belted beige Bermudas began. Under one arm he carried a stack of shiny red books, under the other, a case of beer. A can opener glistening gold in the sunlight dangled from his belt loop, fastened with the twist tie from a green garbage bag.

Bud was not the sort of man June’s mother usually dated. Mona preferred men with a little more polish. But over the past couple of months, he’d been edging more and more into their lives.

The doorbell rang. “Loser,” thought June. Turning away, she walked back down the hall and into the kitchen. “What to eat, what to eat.” There was no doubt about it, June was gaining weight. Just when she was supposed to be blossoming into womanhood, growing tall and willowy like the heroines of the romance novels she’d read at her grandmother’s house last summer, June had stopped growing up and had started widening out. She wasn’t sure how it had happened. Even worse, her mother had noticed it too. For her thirteenth birthday, Mona had given her The Teen-Age Diet Book, inscribing it, “My Dearest June, To help you be all you can be.” One of the suggestions in the book her mother had particularly liked was to cut pictures of models from magazines and tape them to the refrigerator. Unbridled cravings could be reined in by these pouty, sultry Cosmo girls poised in accusation as you reached for a piece of pie or chocolate cake. “Remember girls,” chided the book’s author, “nothing tastes as good as being thin feels.”

Mona told her she was lucky her complexion was good. “Peaches-and-cream skin,” she called it. But it was clear to June as she tore the wrapping off the present that came with the book, a box filled with cosmetics, lotions, and creams, that the rest of her needed work. June had blinked back tears as she removed the gifts: a pink and white Remington Princess electric shaver, eyebrow tweezers for thinning and shaping, eyelash curlers, a wand of Cover Girl mascara to lengthen and thicken, and a jar of florescent green Dippity-do gel to add lustre to her dull, limp hair. Later that night she’d rammed the presents under her bed, then snuck into the kitchen and shoveled down a third piece of mocha almond fudge ice-cream cake that had been special-ordered for the occasion.

The doorbell continued buzzing, insistent now, short and long alternating rings. “Like that’s going to help,” June thought. Smiling to herself, she scanned the contents of the refrigerator. Carrot and celery sticks, brown at the ends, floated in murky water in an uncovered Tupperware bowl. A few shriveled oranges lurked behind the skim milk. She opened the freezer and removed a small container of chocolate ice cream she’d hidden in the back. As the door banged shut, the picture of Charlie’s Angels that Mona had ripped from an old TV guide shook loose and floated to the floor. June stomped it with her foot. She grabbed one of the dirty spoons from the counter, rinsed it under the tap, sat down at the table, and began to eat.

“June!” Mona shouted. “Jesus, June! Where are you? ” June kept eating. “Bud’s here and I’m not ready. June, for God’s sake, answer me!”

Mona’s heels clicked fast and loud as she entered the kitchen. “Be there in a minute,” she yelled in the direction of the front door. “Didn’t you hear me? Jesus! You’re not eating ice cream, are you? It’s ten o’clock in the morning!”

“Leave me alone. Just leave me alone!”

“What do you mean, leave you alone? Are you even packed yet? We have to get going. I don’t know what’s wrong with you.” Her mother ground out her cigarette. “Get moving. Right now.”

“I’m not going.”

“You are going.”

“No. I’m not.”

“You are. Stop eating that goddamn ice cream and pack your stuff.”

“No.”

“I mean it. Get in your room right now. For Christ’s sake, you’re the one who’s always bugging me to take you to Montreal.”

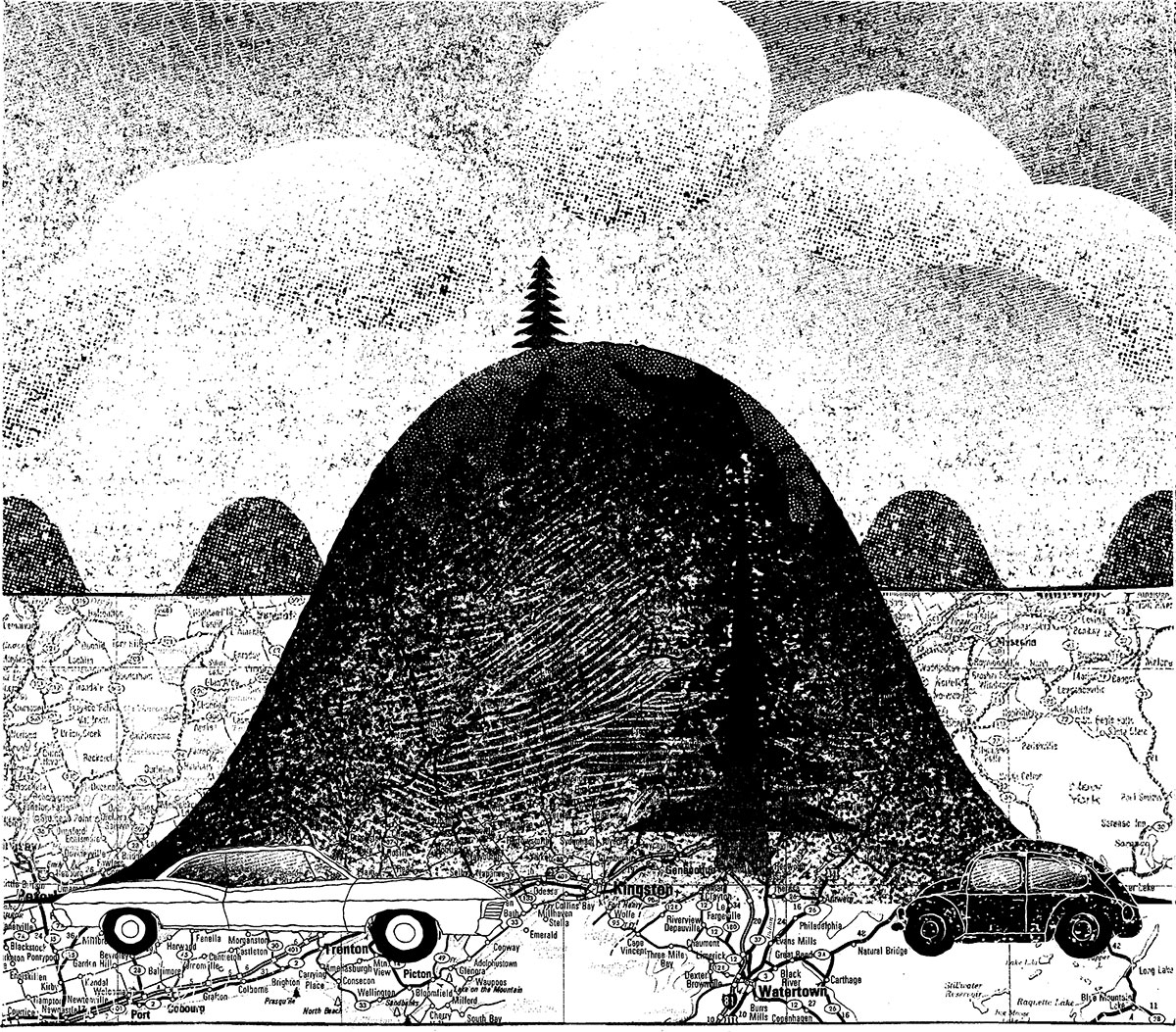

June thought of the nights just after her father had left, when she and her mother would sit huddled over an old school atlas, planning summer vacations they never took. They would trace the pink and yellow highways from London, around Lake Ontario, along the St. Lawrence, to Montreal, the most exotic Canadian destination they could imagine. They had even written to the chamber of commerce for city maps and tourist brochures. The big trip they would take one day, just the two of them.

“Yeah. But not with him.”

“Oh, so that’s it. Not with him. Well, Bud is the only way we can go. You’re lucky I have a friend like Bud who wants to take us places.”

“Bud’s a pig. And he’s also married. I wonder how his wife feels about our little trip.”

“She’s probably glad we’re going, so she doesn’t have to. They don’t really get along, June. I’ve told you that before.”

“Right.”

Mona lit another cigarette. Her face was red and puffy from the shower. Beads of perspiration had formed on her forehead and her eyes were bloodshot. Her hair was rolled tightly in pink cushioned curlers. She was wearing a bra, panties, spice-coloured pantyhose, and black pumps. June hated seeing her like this. The fleshy intimacy filled her with revulsion.

“Whether you like it or not, you’re coming with us. Go get packed. Right now!”

June stood up slowly, as if a huge wad of bubble gum was reluctantly releasing her from the chair, pink sticky strands drawing her back.

The doorbell began ringing again. A long constant drone.

“Oh Christ,” Mona said, “Bud’s still at the door! Get going, June. Move, please.” Her mother shifted slightly as June veered around her, trying to make it through the doorway without touching her.

June dragged her suitcase into the living room. Mona and Bud were on the couch, paging through one of the books he’d brought in from the car. When her mother saw her, she abruptly withdrew her hand from the inside of Bud’s thigh. “Gross,” June thought.

“Hey there, Junie,” Bud said, grinning, “all ready for our trip? ”

“Like I have a choice,” she answered. “It’s June, by the way. Just June.”

“Watch it, June,” Mona said, grabbing a beer from the case on the floor. “Open this please, would you, Bud? ”

June glared at her mother.

“We’re just havin’ a couple,” Bud said, “to get us going. Then I’ll put some in the cooler, you know, to have a few for the road.”

He wiped condensation from the bottle with his T-shirt. “Here you go, Mona.” He turned to June. “I was just showin’ your mother some of the merchandise I’ll be sellin’ at the convention.”

Bud was in sales. He was a Hallmark distributor. Cards for every occasion, candles of all colours, ceramic figurines with sentimental sayings littered his car. He gave the red book to June.

“If you flip to the front there…”

She turned the book in her hands and glanced at the title: Family Traditions: A Hallmark Guide to Creating Special Times. As she passed it back to Bud, some of the black ink from the title smeared and rubbed off on her palm.

“Your…merchandise book seems kinda cheap,” she said, wiping her hand on her cut-offs.

“June!” her mother said.

“That’s O.K., Mona. Junie here—I mean June—is right. It’s whatcha call the lower end of the market. It’s really what’s inside that counts. And it’s pretty special, I think. Pretty special, indeed.” He yawned without covering his mouth. “Well, ladies, time to go. Or, frappe le chemin, as they say in ‘K’bec.’”

“I put most of the stuff in the trunk, June, so you’d have lots of room there in the back. Well, we’re all set, ladies,” Bud said, jangling his keys and whistling as he slid into the driver’s seat.

“Damn. I forgot something,” Mona said, opening the passenger door. “Back in a flash.”

As June climbed in, the vinyl upholstery of the seat was hot and stuck to the back of her bare thighs. The car reeked of stale cigarettes. She struggled with a handle and rolled down the window, wriggled in further, and settled in behind Bud.

“This is for you,” he said, handing her a pillow, “in case you get sleepy, want to take a nap.”

June tucked it in beside her, against the hard edge of the door. The seat was long and wide, and even straightening her legs she could lie almost fully out.

A few minutes later Mona reappeared, hurrying down the stairs and flinging herself back into the front seat.

“There,” Mona said, a little breathless.

“What’s that? ” June said, eyeing the ratty plastic bag Mona stored at her feet.

“Just something I wanted for the trip. Now,” Mona said, settling into her seat, “we’re all set.”

As Bud pulled out of the driveway and headed for the 401, June remembered the car trips she used to take with her parents, back when they were still a family. They’d had a Volkswagen Bug, blue-grey, dotted with red rust. It was the car that had brought her home from the hospital when she was born, and the car her dad drove away in the day he left, more than two years ago now, just before her eleventh birthday.

Mostly, they travelled to her grandparents’ cottage. Her parents were always late and always rushing and always in a bad mood. Her father would pack the back seat so there was only a small space remaining, just big enough for June. The cage that held her cat, Smokey, was right beside her. From time to time she would peek at him through the wooden slats to make sure he was still alive. Up front, her parents would argue about who was to blame for each wrong turn, about how long they would stay at her grandparents’, and about other things she didn’t understand.

She hated those trips, trapped in the back for six, sometimes seven hours at a time. But she loved it when they finally arrived—seeing her grandparents, riding in the motorboat, and wading into the cold, clear lake.

On route, her parents often stopped at legion halls of small towns they were passing through, towns like Orangeville and Fenelon Falls. June waited in the car, the window rolled down a crack, looking through picture books, glad for the quiet minutes with Smokey while her parents drank at the bar. She’d imagine the sour, salty taste and the cool smoothness of the pickled egg they’d bring her when they returned. Sometimes, she got two.

Bud was an idiot, June thought, but at least he and Mona didn’t fight, and June had so much room back here, all to herself. Opening her knapsack, she sorted through the items she’d brought for the car ride: one bag of Fritos, two Mars bars, two cans of Orange Crush, and two books. She pulled out Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret, by Judy Blume. She’d borrowed it from Debbie, who’d read it as part of the mother-daughter group she attended with her mom. The group was sponsored by WomanPower, a feminist organization to which some of her friends’ mothers belonged. June’s mother was not a member. Mona and June had registered for the group, but had gone only once. “I’m sorry,” Mona had said after the first night, “I can’t do it. I’m just too tired after work.” June kept up with the group’s reading list, and Debbie lent her the books.

June’s other book for the trip was The Happy Hooker, by Xaviera Hollander. She had found the musty book in a box in the basement. She read it at night, under the covers, with a flashlight. During the day, she read Judy Blume. June stared out the window as they drove east: past the flat farm fields near Thamesford, home of the Ingersoll cheese factory, and the cement works at Beechville. Her mother’s shout pulled her back into reality.

“June! Bud’s talking to you.”

“Oh. Sor-ry!”

“I was just sayin’, June, I have a little job for you. Same one I give my daughter, Chrissy, when we take a trip. See, I put the cooler down there by your feet? On your mother’s side? On the floor? ”

“Yeah…”

“Well, those travellers should be plenty cold by now. When I say, ‘Beer me,’ I want you to reach in there and pass one up front. By the way, I put a couple of extras in there for you too, Mona.”

“Thanks, Bud. I may have just one.”

“You gotta be careful, June. Pass them real low, between the seats. Otherwise, the cops might see and get the wrong idea,” he said. “O.K.? You got it? ”

“Yeah…I got it,” she said, passing a beer up front. She ripped open her bag of Fritos and picked up her book.

June read and dozed as they headed east, past Toronto, Oshawa, Cobourg. They stopped at a rest station outside of Belleville to stretch their legs, “use the facilities, and chow down,” as Bud put it. In the Esso restaurant, food was served cafeteria style. Mona and Bud waited with their trays by the hot plate, Bud chatting at length with the waitress, asking for her recommendation, the “specialty” of the house. June hung back, trying to pretend she wasn’t with them. Didn’t Bud notice the other people in line behind him, their shuffling feet and their exasperated sighs? June dawdled by the display case, faking interest in the tiny glasses of orange, grapefruit, and tomato juice, and the rows of desserts: cherry and lime Jell-O cubes with dollops of whipped cream, rice and chocolate pudding topped with maraschino cherry halves.

“June,” Bud hollered, “come and give Betty here your order. She’s sold your mother and I on the hot turkey sandwich. Should we make it three? ”

Head down, June slunk over to join them.

“O.K.,” she said. “Order me the sandwich. I’m going to go find a table.”

Anything, she thought, to get away.

“Good thinking, kiddo.” Bud said. “We’re right behind you.”

Bud dug into his meal with gusto. “That Betty was right on the money. Gravy tastes just like homemade.”

“Does your wife make good gravy, Bud? ”

“June!” Mona said sharply.

“Well, to be honest, June,” Bud said slowly, “my wife really isn’t much of a cook. In fact, I make most of the meals at our place.”

“Well, I’m glad your enjoying your lunch,” Mona said, reaching across the table and patting his hand. “I like to see a man eat. As for me,” she said, lighting a cigarette, “I’m stuffed.”

“But you barely touched it,” Bud said. “Not hungry, Mona? ”

“Just watching my waistline,” Mona said, looking over at June.

June glared at her mother and shoved a forkful of French fries and gravy into her mouth. She chewed noisily, her mouth partly open.

“Your manners, June,” Mona said. “Really!”

“Really!” June mimicked. “Really!”

Back on the road, Bud shoved a tape in the car stereo and turned up the volume.

“Oh God,” June groaned, covering her ears, as “Are You Lonesome Tonight? ” blared from the speakers.

“Don’t like the King? My Chrissy is a big fan.”

“Figures,” thought June. “Can we please listen to something else? ”

“We can see if I’ve got something more to your taste,” Bud said. “Mona, rustle around in the glove compartment. There’s a few tapes in there.”

“I have something,” June said, thrusting a cassette into her mother’s hand.

“Can we please hear that? Please? ”

“Bay City Rollers? ” Mona said, turning the tape in her hand. “No, June. We’re not playing this.”

“Can’t say as I’ve heard of them,” Bud said.

“They’re some teenybop boy band June and her friends listen to. You wouldn’t like them at all.”

“They’re great musicians,” June said, her voice rising. How could her mother even say that? “You don’t know anything.”

“I know we’re not going to listen to it,” Mona said firmly. “Bud and I are big Elvis fans. It’s his car, and we will enjoy the music he likes.”

“But—”

“I don’t want to hear another word.”

“I hate you! You ruin everything.”

June flung herself across the back seat and turned on her side, facing away from them. She buried her head in the pillow, squeezed her eyes tight to stop from crying, and within a few minutes was sound asleep.

“Wake up, June!” Mona’s voice startled her. “Wake up. We’re almost there.”

She sat up and looked out the window. She rubbed sleep from her eyes and brushed corn-chip crumbs from her lap.

“Where are we, Mom? ”

“Dorval. About half an hour from Montreal. You know, Bud, this is the first time we’ve been outside Ontario, June and me. The very first time. Right, June? ”

“Yeah. Hey, Mom!” June said, so caught up in the excitement she forgot to be mad. “Look. There’s a sign in French.”

“Where? Oh, I see it,” she said, turning to her daughter. “So, Bud and I were talking, June. When we get to the convention, in about ten minutes, Bud’ll have to go in and make an appearance. So, I thought, if you wanted, you and I, well, we could go right into downtown Montreal. Check things out. Maybe go into one of those sidewalk cafés? Have coffee in a bowl, like we saw that time on TV? ”

“O.K.” June said, “I guess that would be O.K.” She didn’t want to seem too eager, didn’t want Mona to think she was completely forgiven, but June was thrilled.

Mona touched June’s arm. “That’s great, then. That’s our plan.” She reached under her seat, pulling the ratty plastic bag onto her lap. She took out the atlas, the one she and June had pored over years ago. Its pages were crammed with creased city maps of downtown Montreal and tattered pamphlets highlighting attractions and sites.

“We still have that? Where’d you find it? ” June had assumed that the atlas, like their plans, had long since disappeared.

“I’ve kept it tucked away,” Mona said, smiling. “Just in case.”

June leaned over the back of Mona’s seat, breathing in the smoky perfumed scent of her mother. “Where are we gonna go first? ”

“I’m not sure. Maybe to the old city? ”

“Well, this is us here,” Bud said, pulling up to the Howard Johnson’s. The sign out front read, “WELCOME HALLMARKERS BIENVENUE.”

Mona clicked open a compact. She applied red lipstick and dabbed powder on her nose. She passed a hairbrush to June. “Comb your hair, honey. You want to look nice for Montreal.”

June gave her hair a few quick strokes.

Bud hopped out of the car and removed the case of red books and three other boxes from the trunk. He took out a “HI! IT’S BUD!” name tag and pinned it to his T-shirt. He slid out the suit bag he’d stored carefully across the luggage. “Looks like I got all the necessaries. Here you go, ladies,” he said, tossing the keys to Mona.

“Come up here with me,” Mona said to June, ejecting the Elvis tape and replacing it with the Bay City Rollers’ Greatest Hits.

June climbed into the front seat as the first notes of “Shang-A-Lang” filled the car.

“Well, here we go, June,” Mona said, starting the car. “Here we go.”