Dad always said when you cross the path of an animal in the backwoods, best thing to do is stay put, and under no circumstances pose a threat. But if you were in a car it was a different story. If something got in his way—fuck it.

I was lying in the back seat, and Mom was watching the treetops speed by. Wham played on the radio, and Dad mumbled something about art fags and the death of rock ’n’ roll. He peered through the windshield and perked up.

“Would you look at this? Brats are practically on the road, for Chrissake.”

He looked for me in the rear-view mirror and said, “Hey, kiddo. Isn’t this your girlfriend up ahead? ” and hit the gas. Mom grabbed the dashboard.

“Don’t you…”

My head smacked the roof and I rolled onto the floor, legs up over my head. Mom was grabbing at the air behind her, struggling to right me. Dad fought to bring the wheel around and we fishtailed to a stop.

“Stupid, fucking girls!”

It wasn’t the usual ping of a chipmunk bouncing off the tire wells. Whatever we’d hit, it’d gone under both wheels. Mom cupped her mouth, to keep from puking or crying, I couldn’t be sure.

I scrambled up onto the seat and counted three of the Chambers girls—five, seven, and nine—huddled against the rocks. The fourth was missing. I stumbled out of the car and motioned to the youngest, a deaf girl who wore a box around her neck you had to yell into.

“Elsa, where’s your sister? ”

She shook her head. I grabbed her shoulders and screamed into her chest.

“Where’s Cass?!”

She came out of the brush carrying a long stick, burrs stuck to the hem of her Adidas shorts. We were in Grade 9 together; best friends forever since the summer.

“Your dad’s an asshole, you know that? We were just trying to get it off the road.”

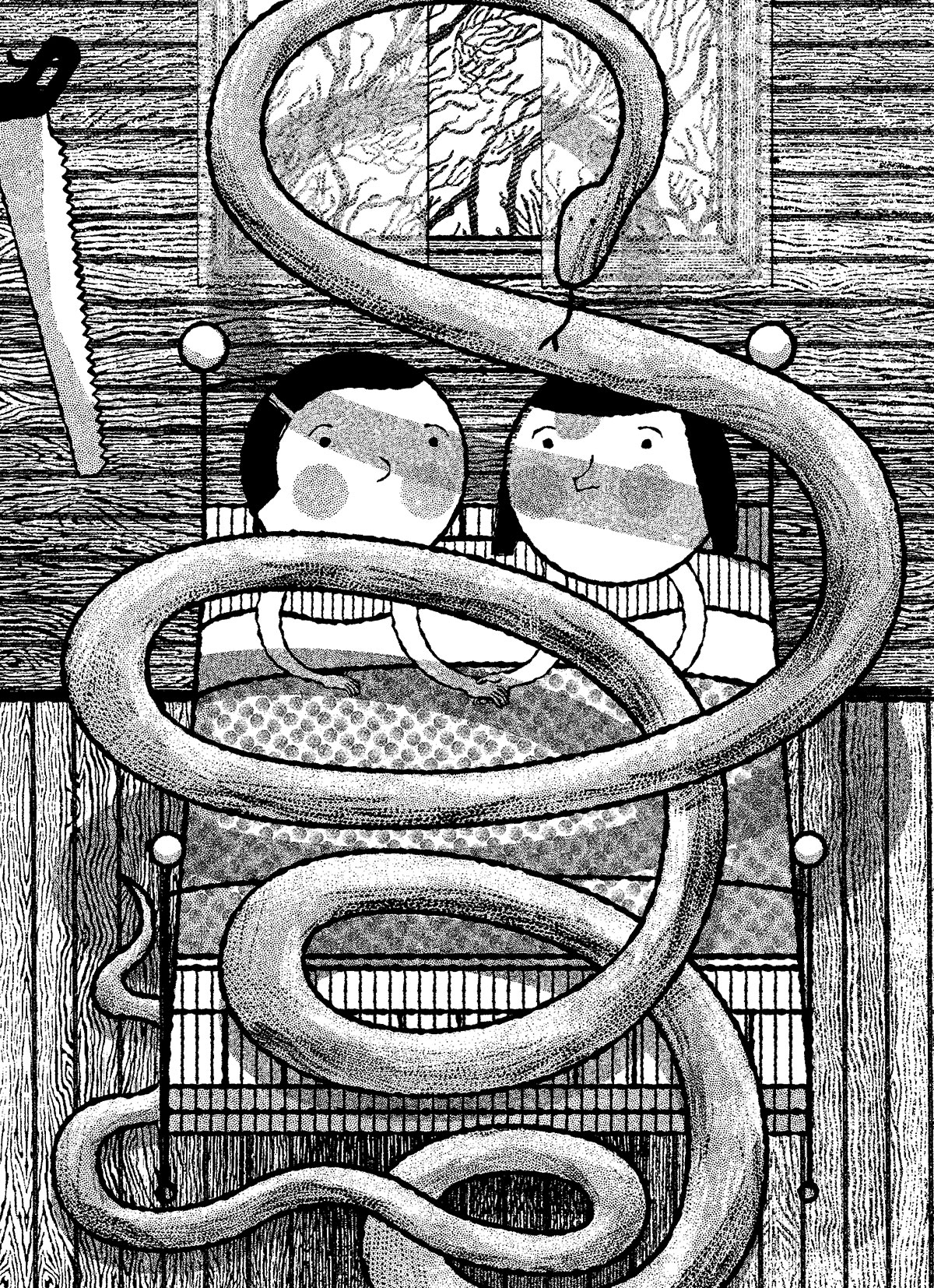

“It” was a snake, massive and thrashing like a fire hose. As I got closer, it stopped and pressed its head flat against the asphalt, hissing like a leaky tire. Gregg, the kid next door, once told me about this girl from someplace foreign like Russia who’d fallen asleep in a tomato patch and when she woke up she was in the hospital choking up a garden snake. Gregg kept jabbing his tongue against the inside of his cheek, and laughed so hard he snotted himself.

Cass was trying to scoop the snake up off the road. Mom was running up the shoulder, waving me back. The snake kept rolling over, belly-side up.

“What the fuck is it doing? ” Cass asked, thrusting the stick harder.

Dad spun the car in reverse, clipping Mom as he passed.

I grabbed Cass’s pinkie and leaned in close to her ear.

“Playing dead.”

When we got home, I waited outside, cracking twigs and watching Dad pace the front room. In the winter, he worked recovering snowmobiles from the bottom of Kawagama Lake. During the summers, he’d been managing the Tasty Creem: Home of the Foot-long Hot Dog.

One day he told us, through forkfuls of mashed potatoes, that a regular named Barb had convinced him to come work for her selling cars. He nodded happily to himself, chuckling at some far away thought.

“She says I have a killer smile, and that she’d buy just about anything from me.”

He scraped his plate clean, his knife hanging useless in the other hand.

“This is really good, hun. Any more? ”

Now, Mom was on the phone with Flora Robinson, the volunteer co-ordinator for portage routes. Every once in a while, Dad looked out at me, helpless, like he’d really done it this time. Mom stood nodding, pressing her thumb into the flowers in the wallpaper like she was extinguishing a bug. She snapped her fingers at Dad to get her purse, and pulled out the cheque book. Dad stormed out of the house, up to the welcome tree, on the main road, where he pried off the family’s name. I’d painted that in summer camp when I was five.

“Never fucking wanted fucking hicks to fucking find us anyway,” he spat.

Dad’d killed Beloved Big Ben, a rare eastern hognose. Turns out there’d been only five sightings in the last ten years, six if you counted ours. The next weekend, Mom dug out her bug jacket from the back of Dad’s shed and started the first of twenty-seven-years’ volunteer trail maintenance. Not long after, Dad left to live with “civilized people” in the city, and a pregnant Barb.

I woke up one morning to find Mom standing in my room.

“What’s say,” she pondered, petting the ceramic figurines she’d used to decorate my room, “we do something special soon. Hey, baby? Just us gals? ”

Just us gals. That’s what we’d become. I started to spend more time at Gregg’s. He was always horny, and we’re pretty sure he gave me lice, but he was the only other kid on the circle; all the others were two hills away by bike. On a good day, you might make it over one, but never both. Mom got sick of wondering if I’d make it back—“Kids can have strokes, too,” she’d say—so I had to settle for hanging out with Dirty Birdy Gregg.

We spent most weekends spitting, back behind his boathouse. It usually ended up dribbling out of my mouth, which sent Gregg into a fit ’cause he said it made me look like the girl from his uncle’s porn mags. He showed me. Sure enough, there she was, stuck in a fishnet with a line of spit running down her chin.

During the school week, though, I barely to spoke to Gregg. And all he wanted was for me to set him up with Cass Chambers. Ever since she’d pushed him up against a locker for touching her butt, he was all, “I’m gonna give it to her so bad.” Like he ever had a chance.

Cass was new to town from the city. There were rumours she’d been put in a hospital for a drug overdose, but she told me she’d just left her tampon in too long. We let people think whatever they wanted to. I didn’t really want any other friends.

When Cass first moved here, I biked past her house so much her parents made her come out and invite me for a swim. I borrowed the nine-year-old’s one-piece and circled the edges, churning the water into a whirlpool. Cass sunbathed on an inner tube. Her boobs were really big; I’d seen her change in gym class. She was taller than the rest of us, almost six feet, and broad. “Big-boned,” they’d call her.

She squinted at me, stretching her arms out to steady herself.

“Stop it. You’re making me sick.”

She sank through the centre of the inner tube and disappeared under the surface.

When I was a little kid, I used to take a rubber shark into the bubble bath and scream when it bumped into me. I kept hoping I’d get used to it. When Cass brushed through my legs that day, I peed a little.

That’s how it started. Every day I saved a seat for her on the bus. We crushed our legs against each other and every bump sent shivers below.

Mom was hell-bent on ridding the house of anything Dad, starting with his tool shed. I offered to clear it out, on the condition that I could use it as a bunkie and have Cass for a sleepover. My real plan was to move into it, so I’d only ever have to go inside the house to eat and use the bathroom. Little by little I was moving things in, and keeping some of what I’d found, like the dirty magazines under the floorboards.

All that week, I taunted Gregg that Cass Chambers—Cass Chambers—would be right next door, naked under her sporty T. Come Friday, I followed him off the bus and up his drive, yelling that he shouldn’t be such an idiot just ’cause some stupid girl didn’t want to go out with him. He spun around and hocked a loogie at my feet, like I was trespassing.

“Fuck off, cunt.”

I waited on the deck for Cass to arrive. Mom came out and leaned a glass of wine on the railing, looked out over the bay.

“I don’t know why you two would want to sleep in that hole. It’s not very nice for your friend.”

I held my breath.

She turned to face me, brushing my bangs hard off my face.

“Your father never liked this girl, y’know that? Said there was something about her.”

I kept my head low and stayed quiet.

Eventually she went back inside to top up her glass. She got out the vacuum, running it back and forth over the shag rug, paying special attention to the stain Dad made when he dropped a platter of barbecue chicken. She yelled over the noise to no one in particular.

“I think maybe we’ll tear down that shed, after all.”

“Mom!”

She yanked the cord from the wall.

“Look, if you want to live with your father, go ahead! Call him right now. See what he says. Maybe you’ll be happier then. Get what you want…”

The sound of gravel signalled Cass’s arrival. She got out, carting a duffle bag. Without a goodbye, her mother lurched the station wagon out into the circle, spinning a blast of dust behind her.

“The woman can’t even come in to say hello? What’s wrong with people? ” Mom huffed.

She took what was left of the wine into the den to watch Wheel of Fortune. I took Cass straight to the bunkie, sick that I might have to move away to the city to live with my father and his new family.

We ate potato chips and drank grape soda and listened to music Cass had taped from the radio; groups I’d never heard of. Tones On Tail. The Cure. The Smiths. My favourite was Bronski Beat. I pictured the singer not much older than us, like one of the lonely boys in choir. Skinny, sunken chest, tiny around the waist.

I showed Cass the porn mags. There was a picture of two women in a science lab, naked and straddling a telescope, sucking their fingernails. I don’t even want to know what’s under my fingernails. We decided to look at yearbooks instead, pointing to all the girls we thought were pretty. Cass ran her finger up and down the rows, past my picture, and onto the next page.

The bunkie was getting light again. We could barely keep our eyes open. Cass was pushing letters into my palm like I was Helen Keller, her head nodding toward me. Across the bay, a small waterfall rushed. Cass’s breathing settled into a soft gurgle, the sound of water drowning. It ached. If I could just kiss her once.

There was a crunch and I woke with a start. It was morning. Cass had her head on my pillow and her arm around my waist, and someone was outside the bunkie tiptoeing away.

Breakfast had been laid out but Mom was nowhere to be found; only a note saying she’d be back sometime later and that Cass’s mother was expecting a call the second we woke up. It was noon already.

“We’ll pretend we didn’t see the note,” I begged.

We wasted the day biking into town for candy, ducking off the road each time a car passed. When we got back, the answering machine was full of messages, one from my father wanting to know why Mom wouldn’t just sign the damn papers so they could “put this behind” them. All the other messages were from Mom, wanting to know where I was. In the background there was banging and hissing, the zrrr-zrrr of an auto shop.

The phone rang.

In the distance, Mom was yelling, asking how much fucking longer it could take to replace a goddamned windshield. Then she was deep in my ear.

“Where have you been? ”

“Mom, are you all right? ”

“All right? No, I’m not all right. Fucking thing just ran right out into the road! Your father always had to do all the driving!”

I gripped the phone cord, winding it tight around my fingers.

“Where have you been all day? I needed you.”

Cass was backing out the door. I mouthed for her to wait.

“Good God, is that her? Is she still there? I should’ve listened to your father. He saw it. Why do you think he left? Coward never faced a thing in his life. You must think I’m such a fool. Under my own roof!”

She was hysterical, fuming. Something had run into her car and she couldn’t afford this and it was all my fault because she’d been upset and how could I do this to her and why didn’t anyone ever care about her feelings and—“I want that fucking girl out of my house by the time I get home!”

I slammed the phone down and started to cry, throwing vegetables into the sink. Cass came from behind, crossing her arms around my chest. I shrugged her off.

“You gotta go. I have to get dinner ready.”

She came again, resting her lips against my neck, simple and tender, her breath thick and crackling with Pop Rocks.

Overhead, a helicopter strained under the weight of its cargo, diapered in a sling like a child on a fair ride—the moose that had hit Mom. Drivers craned their necks to get a better look. Gregg tightened his grip, trying to concentrate, growing hard under his comforter. And two young girls opened their mouths to each other over a pile of Brussels sprouts.