“Hey, Matty.”

He didn’t look up. He was sitting at the counter, his attention entirely focused on the crossword puzzle. He never said hello. When he did look up, it was usually to gaze at the consoling face of ageless country-music belle Evangeline Reynolds on the poster across from him. She was a popular figure for crushes among men of his generation and disposition.

In any case, Matty didn’t look up, so I took my CDs to Matty’s Music Mart’s friendlier employee, J.C. He stood near the cash register, with a pricing gun, going through a stack of discs. Mean, throbbing bass tones and clattery percussion emanated from his headphones. I stood in front of him. I thought, “Why pretend he can hear me? ”

“I have some to sell.”

He nodded off beat.

I put my discs on the counter. “I’m gonna look around.”

J.C. nodded again.

Slightly wheezy from my brisk walk through the April drizzle, I inhaled deeply. There was panoply of familiar store smells: the faint remnants of yesterday’s after-hours cigarettes, the aroma of moist industrial carpet, the tomatoey tang of microwaved pasta and takeout pizza. In every second-hand record store, you can count on finding the scent of middle-aged men who live alone (a combination of B.O. and burnt nutmeg) and a sharper whiff of cat piss. Then, of course, there was the mustiness that emanates from five hundred thousand LPs, the store’s holdings according to the sandwich board on the sidewalk. Individual records rarely smelled of anything. I remember a few that literally stunk: a Captain Elephantiasis album drenched in Old Spice, a Room Service sleeve as rank as a vomitorium, a green-vinyl Edward Townes single that would’ve been valuable had the disc itself not stunk of skunk and boiled cauliflower. After touching it, I asked Matty if there was somewhere I could wash my hands. “This ain’t a bus station,” he said.

Matty’s holdings were so enormous and overwhelming, I had to be strategic about my browsing, lest I got caught in the store for the rest of the day and come out too poor for beer. I’d already investigated certain sub-genres: Welsh punk rock, East German psychedelia, Polynesian reggae, outlaw country ballads. My most beloved find in the latter category was Devil Woman with Angel Eyes, by Freddy Capp and the Six Pack. The back sleeve portrayed the scantily clad devil woman about to be cornered, in a hillbilly gangbang fantasy, by Capp’s drooling posse.

A few months before, I’d also found the record that had made me move to New York—I’d given away my last copy to my ex-girlfriend Linda. The band and the album were called Asphalt Diary. It was recorded in 1975, but I heard it in 1986, when I was thirteen. The singer, John J. Murphy, named himself after a park near Stuyvesant Town. He was a published poet and a committed junkie. Delivered over a musical backing at once elegant and abrasive, Murphy’s lyrics put a romantic spin on New York street life—songs bustled with hippie burnouts, huckster con men, struggling immigrants, and girls half-dead to the world. They often played CBGB in the days before it opened a gift shop. I fantasized about life in the city Murphy portrayed in all its scum-encrusted glory. (It was cleaner by the time I got here.) I wrote despairing free verse about heroin addicts living in the Evergreen Hotel. I bought a brown leather jacket from the Salvation Army but was too shy to wear it outside my bedroom. I practised a scowl. I planned my escape from the genteel suburbia of Fairview, Ontario, a place without street hassle. I never wanted to live on a golf course again.

Another big score was a not-too-beat-up copy of This Morning Is for You, the sole recording by Daisy, a sister act from California whose father-manager was convinced the girls would be global pop superstars. They weren’t—the sisters could barely sing or play. The record was a disastrous flop, but over the next three decades Daisy’s music gained a storied reputation for both its inspired incompetence and its chance moments of beauty and grace. I’d heard a few songs on a college radio show, and I loved them like crazy.

“A mint copy’s worth five hundred dollars,” Matty said when I brought it to the counter. The one he was selling was so messed up with water damage it could’ve belonged to a porpoise. I argued him down from ten dollars to six dollars. The vinyl itself sounded fine on my turntable—those sisters belonged in a world of their own.

I was feeling a little starved for human voices that day, so my category of choice was spoken word and comedy. This trove had already yielded treasures like Lenny Bruce’s ace 1967 LP Wisenheimer Deluxe and a double album bearing the imprimatur of the early-sixties skin rag Boudoir. The lady on the record cover promised to tell me “the things every man needs to know.” I hadn’t listened to it yet, saving it for a special occasion.

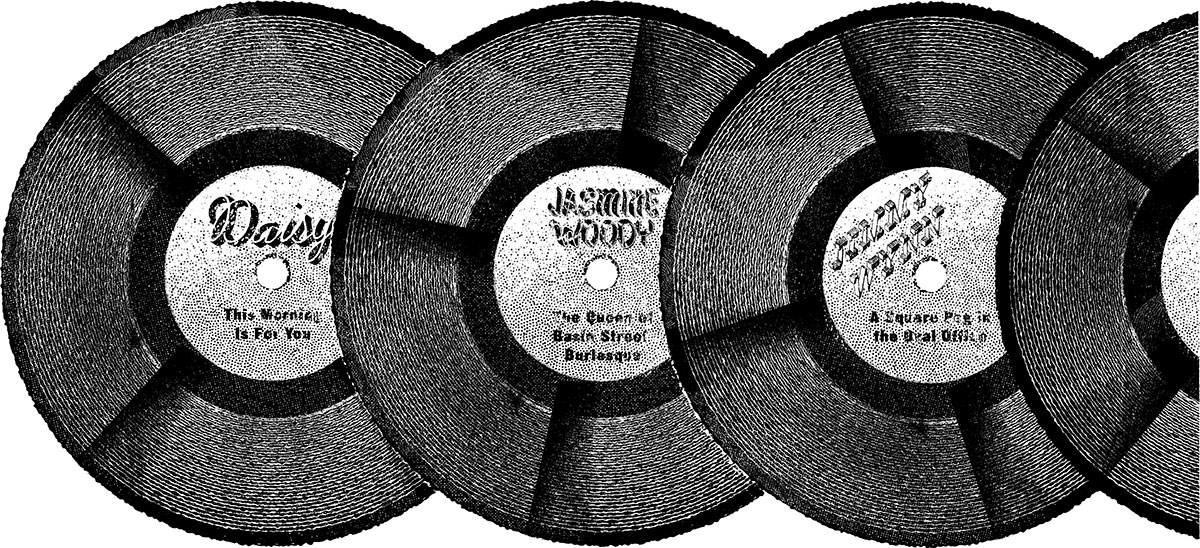

I found Jimmy’s record when it slid out with its neighbour Jasmine Woody: The Queen of Basin Street Burlesque. Neither cover had—as I’d initially hoped—nudity. One did have a president. At first, I thought Jimmy’s record must’ve been campaign songs or a compilation of speeches—I had often seen a late-night infomercial for a four-CD set of Cannon’s “greatest oratorical achievements.”

On the cover was a man in a dark suit and a blue tie to match his eyes. He was giving Cannon’s signature double-thumbs-up gesture. He stood before a wooden desk and a U.S. flag in the Oval Office, or, rather, what the Oval Office would look like with balsa-wood furniture, paper rugs, and cardboard walls. Despite the chintz, the picture closely resembled a famous photo that had been on the cover of Look in 1961. It was one of the most famous images of Cannon from his early days in office. The imposter here bore a definite resemblance to the president. Sure, his hair was too dark, his chin too weak, and his features less attractive on the whole, but he had the body language right (the forward tilt, the raised shoulders) and smiled the same brilliant, toothy smile.

Across the top ran the title in the same florid script preferred by this nation’s founders. It read: A Square Peg in the Oval Office. Underneath the man’s shoes (matte black Oxfords, just like Cannon’s) was a name: Jimmy Wynn. On the back was a list of titles (“Not on the Official Tour,” “The African Ambassadors”) and this note:

This album is for fun. Laugh along with Jimmy Wynn and his gang, the Capital Offense, as they say some wacky things about some of the greatest people of our time. We hope that this record will be taken in the right spirit—no disrespect is intended. The very fact that the folks we joke about are able to laugh with us and enjoy this record is a big reason why we admire them so. Jimmy’s pleased to present the lighter side of life on Capitol Hill. “This country has given me so much in my life, it was time I gave something back,” says our patriotic prankster. “I just hope America can make change—all I’ve got is a twenty.”

The Betsey devoted countless column inches to the most minor and most tangential aspects of Cannon’s life, from his preference for argyle socks to the ratings of his favourite television shows. Yet I’d never seen any mention of Jimmy Wynn. This record smelled more like a lead for a story than it did like skunk or cauliflower.

The fifteen-dollar tag gave me pause. I took the record up to Matty. “Excuse me.” He didn’t bother looking up from his crossword. “Uh, can you go any lower on this one? ”

He peered up from the paper. “What’s that on your face? You get mugged? ”

“No. I cut myself.”

“Hmph.” He took the record from my hands. He ran his hand over the sleeve. “Little scuffed.” He slipped out the disc and had a look. “Barely played. You’re lucky—a first pressing’ll go for five hundred dollars.” Matty looked past me at Evangeline Reynolds, as if asking for her confirmation. “Fifteen dollars.”

“Serious? ”

“That’s my price.”

“The sleeve’s pretty rough.”

“Sleeve’s fine.”

“This can’t be so rare.”

“You got that right. This was a No. 1 record. Sold millions.”

“So why’s it so expensive? ”

Matty stroked his whiskery chin. “Fair question. I remember going through piles of the damn thing when I worked at the record department in a big store on Broadway. Used to keep ’em at the cash register so I didn’t have to run around. The same guy put out another record a few months later. This is the first one, I think. When is this? Sixty-one? ” He scrutinized the fine print on the back cover. “Nah, ’62. Mr. Jimmy Wynn. I used to see him on The Manny Hudson Show. Some people thought he was funny. Struck me as a square. Did Cannon’s voice real well, though. Then, after that day…” Matty drifted off for a few moments, then snapped back hard. “We took ’em off the shelves and never put ’em back.”

“What happened to all those records? ”

“Garbage,” he growled. “People couldn’t get rid of ’em fast enough. Every garage sale had one.” He tapped his finger on the record’s spine. “But seeing as folks did such a good job of making like Mr. Jimmy Wynn never existed, his records are almost rarities.” He drew the disc closer to his chest and eyed me jealously. “I should be asking twenty dollars.”

“How about ten? ”

“Twenty-five.”

“But the tag only says fifteen.”

“That’s a goddamn bargain!” he yelled. He looked sternly at me, then the record, then Evangeline’s all-forgiving face. He shoved the record in my direction. “It’s fifteen dollars! Now get it out of my sight.”

I went to the cash register before Manny tried to take the record back—the last time he’d gotten like this, I’d barely escaped with Daisy. I swallowed my pique over my failed negotiation and hoped that Jimmy Wynn was worth it.

I was very particular about how I listened to records. Compact discs never had the same aura as objects. I had gotten too many for free in the mail for even the ones I bought to seem special. Records had a certain kind of appeal that the discs couldn’t. It was archaeological—on some level I believed that each time I bought a record from a shop or a milk crate on the street, I was rediscovering a past that had been suppressed or neglected. I hated it when a record I found was reissued on compact disc. Sure, the change in format made the recordings seem more permanent, but it wasn’t the permanence those creators imagined. No, they dreamed of someone like me coming along in the hazy, distant future, someone who knew nothing of their lives yet was struck dumb by the product of their thimble’s worth of hope and ambition. I proved that their work had lasted, regardless of whether it ever deserved to. Even if I tore the record off the turntable and smashed it against the radiator after enduring it for fifteen seconds, the gap between present and past was temporarily bridged. I treated every record—whether it was performed by a presidential impersonator, a briefly successful doo-wop group, or even a sad, drunk, middle-aged cowboy in a red codpiece—as an opportunity to fold time.

Thus did I pull the record from the sleeve, lower the stylus on A Square Peg in the Oval Office, and take up my position on the floor of the living room.

Here’s what I heard first.

The crackle of the record mixes with the low murmur of a studio audience. “Ah, testing, testing, one and, ah, two.” The simulation of Cannon’s voice is good enough to silence the audience’s chatter. When they realize, no, it can’t be, there’s a ripple of relieved titters. “I’d like to, ah, welcome all of you listeners to a little something we’ve cooked up for your pleasure.” The voice is smooth yet broadly Bostonian. There’s less of Cannon’s warmth—the charm is spiked with aggression, as if he’s not so confident he’ll be liked. “Connie? Connie, why don’t you come over here and say hello to the nice folks.” “Oh, honey, my hair’s not ready.” The woman’s voice is not so close to the original—the words are too quick. “It’s a record album, Connie. They can’t see your hair.” “But what about the photographers? ” “No photographers, either.” “Then how are they going to see me? ” “The listeners will just have to imagine you in all your, ah, glory.” “Well, I won’t have anyone imagining my hair when it’s in this state.” Laughs from the crowd. I picture a stand of folding chairs, tape on the floor, free coffee, and a sign that somebody holds up to elicit APPLAUSE APPLAUSE APPLAUSE. “And, Theodore, I think your listeners would rather imagine you with your trousers on.” “I would like to say that I am, ah, quite comfortable as I am. The listeners can imagine me however they like. So let’s start the show.”