The problem could have started long ago, when I was a kid or a teenager. I know that. But I prefer to think of it as a recent problem, one that might go away as quietly as it arrived. And I don’t feel a great need to get “better.” They say that, don’t they? The patient must want to change. Well, I don’t.

Even though I’m unemployed, I still get up at six. Some habits are hard to break. As usual, I leave a note for the newspaper delivery man. Every week or so I leave a note. Today it’s a page torn out of the New Yorker, from the front of the book. We call it “the book” in the magazine industry. I don’t know why, but I guess everyone has to have their own jargon. Like people in the Armed Forces calling things “Alpha Delta Charlie” or “H.Q.” or “bogey.” Whatever. Anyway, my newsguy’s name is Simon, so I circle a notice for the play Kennedy’s Children at some little pub in Manhattan and write: “Simon? One of yours? ”

I know that sounds psycho. I know it makes no sense. I mean, it’s not really even a veiled threat or a come-on or even an admission of any kind. It’s just deeply weird.

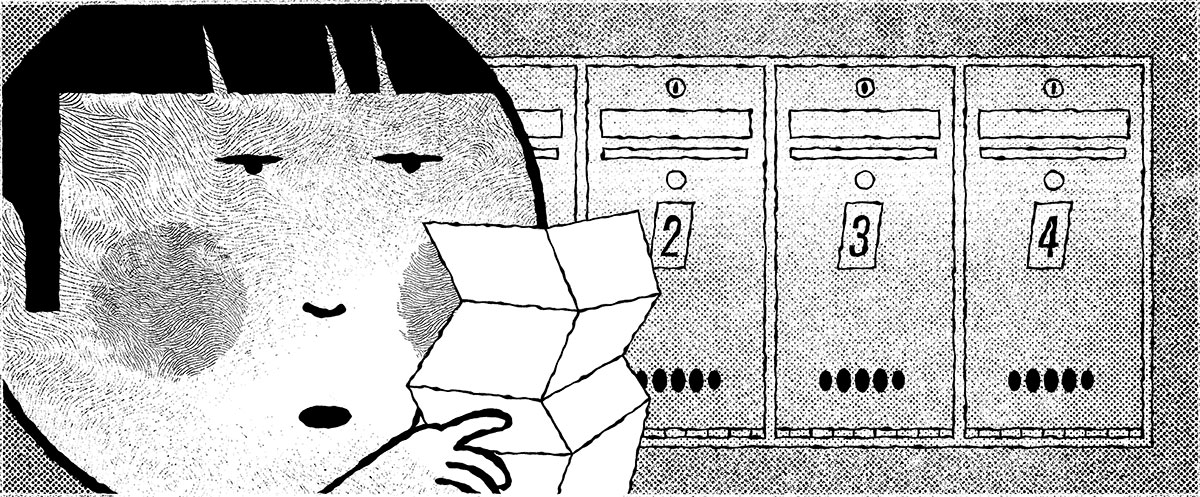

It used to be that Simon would simply look at the notes I left him and not touch them. Now he’s collecting them. I’m not sure why. Maybe he wants to take them to the police. It’d make quite the bizarre collection, I’ll tell you. The first one, the first note I left the poor man, was a little porcelain figurine of a pixie or an elf or something, taped to an index card with the word “Simon? ” written on it in pink pen. The pixie was grotesquely cute, with gigantic black eyes, and it was squirming in shyness or just childish delight. I put it next to the envelope with my weekly cheque. I heard Simon in the vestibule, standing there for a while, not moving. He was probably just trying to figure it out. That’s what a sane person would do. The next week I made out a small hand-drawn map of our street and I put an “X” on a house down the road with the words “Your friends? ” on it. I don’t have the foggiest idea who lives there. I just picked that house because they had Christmas lights still up in April, and that kind of thing bugs me. That kind of optimism, or laziness.

I think I’m angry. O.K., I know I’m angry, but it’s a kind of distant knowledge, like I’m stunned by the anger. Maybe that’s the wrong way to put it. I’m not really numb—instead I feel like I’m going to burst with pure energy. Frankly, I feel like something is happening in my life, after a long period of…I don’t know what. Walking frantically in circles. Working, coming home, sleeping, and going back to work again. I shouldn’t complain, now it’s all stopped and I have free time. I don’t know why I feel like this. At least I’m not staring through the windshield at 9 A.M. at a bumper sticker that says, “DON'T LIKE MY DRIVING? CALL 1-800-EAT-SHIT.” At least I’m not listening to Carol tell me what a bitch Lisa is, and then, ten minutes later, here comes Lisa saying, “What did that bitch say? ” At least I’m not fighting sleep in front of my buzzing monitor when the C.E.O. of the company walks by and everyone acts like they just saw Bigfoot. And, best of all, I’m not wondering why the back of Jim’s neck bugs me so much. Things are far simpler now.

That’s what I’m thinking, anyway, at 6 A.M., weak sunlight pouring in the front window, when I hear Simon coming up the porch steps. Tentative footsteps, to be sure. Poor Simon. He always walks softly, pauses in my vestibule, reading the crazy shit I leave for him, trying to make out what I’m up to. He could always go to the police and lodge a complaint, and the police would come to my door and talk to me, and I’d be forced to stop my shenanigans. I don’t know how I’d feel about that. Sort of indifferent, I guess. Simon could switch routes with another carrier, and then I’d be someone else’s headache. I’d miss him, of course. But I don’t think he’s a runaway kind of guy somehow. And anyway, it’s not like Simon is the only object of my senseless little games.

For instance, this new kleptomania. When I was still on contract with the Gibson Advertising Group—GAG, we used to call them—I didn’t seem able to leave the building without something in my bag. I couldn’t bring myself to walk out empty-handed. A package of Post-its, a box of pens, whatever—even a three-hole punch. What in the world did I want with a three-hole punch? And then, of course, I had to hide it when I got home. Stuff it down the back of a drawer. I was afraid someone from work would come over for a coffee and see this pile of office supplies, pristine packages, and…Well, my mind sort of freezes over what comes next. So into the sock drawer it goes. What’s the point? Why do I steal at all? I just can’t figure it out. I can’t figure anything out.

Pulling up in the parking lot at work in the morning was always a bit of a freaky event for me. I’d park as far away from the door as possible, which distinguished me from everyone else who wanted to avoid breathing any real air or getting a drop of rain or snow on their powdered noses. So, picture this: there are fifty cars bunched up by the door, then an acre of empty spaces, and then my rusted little Honda off by the trees, pointing into them like I just went mushroom picking. And I always arrived late, which means I was always, always nervous and guilty. But I was a temp, so no one cared, no one knew for sure when I was supposed to get in. No one knew what I did, really. My immediate boss was away on maternity, and the replacement thought I wasn’t her problem. She didn’t give a shit what I did, when I came in, or if I ran around nude, as long as I didn’t approach her office door or even say hi. Her eyes would widen with panic when she saw me coming along the narrow divider-lined hall, and she’d duck her head as if something really interesting might be floating in her lumpy child-made Christmas mug with “MUNMY” written on it. Boy, I hated that mug.

So what made me angry? O.K. Let’s pull out the mental snapshots and have a look. Here I am, dressed in a grey suit coat and short skirt, hands in my lap, and my toes pointing together. See that look on my face? That’s what you look like when you’re being “let go.” They wanted my salary back. You’d think a magazine with a name like Mondo Urbo wouldn’t have the nuts to do one of those Stalinist-type purges you see in the bigger outfits, but it did. Me, two designers, the receptionist, and four laser printers gone in one afternoon. The warehouse guy took each laser printer out to the curb, put it down, counted to five, and then picked it back up and walked it to his car.

Next: here’s me being let go from Echinacea News. It was a part-time, fill-in job for the managing editor, Duska, who, it seems, came down with some creeping undiagnosable ailment that required biweekly massage and chiropractic, a fistful of supplements with each breakfast bowl filled with gravel and wood chips, and unending calls in to me, to remind me to do things I’d already done. She was sweet as pie to me but called me “that little whore” when speaking to the publisher on the speakerphone. He’d just wince at me and make mollifying gestures that translated as: “It’s the illness. She’s not herself.” By my best guess, Duska had never felt more alive. She was fifty and still raw from divorce. She was indulging herself and getting even. Still, I suppose it was remotely possible that she had a real illness, one that made her exactly like herself, only more so. One-hundred-and-fifty-percent Duska. So Echinacea News let me go so they could pay for all the pills she got on account of her benefits program. It was either me, they said, or Duska’s health, and Duska was very important. Well, hell. Half a dead monkey could have seen that one coming. But I guess I didn’t. In fact, now that I come to think of it, I’d have to say there’s precious little in life I have seen coming.

I don’t mind that Jim started seeing someone else while we were still going out. That sounds so civilized, doesn’t it? Or maybe it seems bloodless and selfish. It depends on your view of things. But for me it’s true. After five months, I was getting horribly bored. At least that’s what I think the feeling was: boredom. I can’t be sure. But whenever Jim was due to come over, I’d wander around the apartment tidying, and I’d wonder why everything annoyed me. I’d bark my shins on the coffee table and shout at it. I’d drop a spoon and, after a moment, kick it across the floor. I was totally bitched out. But if he called to say he’d see me tomorrow instead, I felt like it was a short Friday at work. I had the whole evening to myself.

Did I learn from this feeling? Look at my life and think, “Hey, I’m bored, here. I have a choice. I can leave Jim. Freedom awaits”? Nope. I waited till he dumped me. And let’s face it, it was much like being let go: I had to clean my stuff out of his drawers, and he paid for the cab home.

So here’s my advice on what to do when kleptomania no longer turns your crank, when the threat of getting caught stealing Post-its is no longer enough to provide that I’m-still-alive signal from inside. You have a closet full of office supplies, right? Well, why not start bringing stuff back?

Suddenly, the stock room is overflowing. My goodness, where did it all come from? There’s the old three-hole punch sitting right next to the new one. Who needs two? The secretary gets raked over the coals for ordering too much, wasting the company’s money, even though she’s been there for eight years, is wound tighter than a kettledrum, and has never made a mistake in her life. So now she’s furious at Accounting, and Accounting is pulling her files apart trying to figure out how she did it. People take sides. They don’t sit together in the cafeteria. Lots of avoiding in the hallways.

Once that becomes boring, you can move on to other poltergeist tactics. Find your personal bête noire, which in my case was the profoundly lazy and nasty Carl, and put things from other people’s desks into his cubicle. Emily’s favourite watch, Lisa’s little purple calculator. Just take them and slip them onto his shelf. If you’re lucky, like I was, Emily will miss her watch, make a big deal about it, and, an hour later, someone will see it in Carl’s space. Oh, the fireworks! Because, you see, Carl would have to be crazy to do something like that. So maybe he is crazy. At first, you’ll hear these prolonged discussions at lunch about why the freak picked the objects he did, and then they’ll start asking why he started stealing now after six years—someone offering, “He’s been stealing all along, we just didn’t know!”—all of it pointing to some uncharted perversion on Carl’s part. Why did he choose Emily’s watch? Well, of course, because he wants her. Someone should call his wife.

Part of me was watching Carl and pitying him, but the pity was largely self-pity—how awful would I feel if I was as bewildered and hated as him. In fact, I was worse than him. Carl was just unpleasant—I was a criminal. Or so I thought. Turns out someone else was worse than me. One night, very late, every computer in the place was cleaned out. Then the thief waited till gag bought thirty new computers and came back a week later and got those ones too, swiping in and out with a supervisor’s card. Turns out I’m a sardine among sharks.

So, with that little gambit run to its conclusion, I had nothing to occupy me. That’s when I started leaving notes for Simon. Actually, I’ve run into Simon in the hall a couple of times. He’s a tall Asian guy with kind of amazing features, smooth and ethereal. Sometimes I think he looks like a Hong Kong movie star. Maybe he’s Korean. I can’t really tell about these things. Anyway, he was late that day, and I was on my way to work. We stood there like it was a bank robbery and we were both waiting for the bad guy to make a move. I don’t even remember how we got out of it, and, thinking back on it, I don’t know who was more scared—me or him.

Maybe it’s that movie-star thing. Maybe that’s why I can’t stop trying to freak him out. Every day he delivers the newspaper, and I take it and open it up to the classifieds and stare blindly at them for ten minutes. Every day I hear his footsteps in my hallway, and sometimes I hear him pause, looking at the note or the picture or the object I left on the mail table for him. There’s something comforting in the routine. It’s a relationship of sorts. All right, it’s a fucked-up one, but a relationship nonetheless. That’s what I’m telling myself, holding my coffee cup, sitting in a little stripe of cold sun on a Tuesday morning, while Simon stands silent in the hall. I’m smiling, the cup halfway to my lips, when he knocks on my door.