The classroom was quiet except for the rustle of turning test pages and the hiss of steam through the metal radiators beneath the windows. The grey-white sky pressed against the thick glass panes that lined one side of the classroom. In the distance, a snowplow’s blade could be heard scraping away the morning’s cover of snow from the school parking lot, and then silence as it dumped its load onto a hulking mound on the lot’s perimeter.

Click… clink.

Jenny Warren’s pen paused at the sound. She didn’t look up, even when she heard another click as a coin hit the metal leg of her chair, wobbled for a few seconds, and then fell with a clink onto the scuffed tile floor.

She sat at the front of the class, facing the chalkboard, her desk pressed against Mr. Alman’s hulking oak desk. From this vantage she could easily read—upside down—her teacher’s attendance records, marks sheets, and daily lesson plans written in bright green ink. Today, his agenda read, “Per.3—Gr.10 Drama Test: Shakespeare, Marlowe and Elizabethan theatre.”

Jenny continued her answer to the question, “Give three reasons why Romeo and Juliet is considered a tragedy,” as she tried to ignore Bradley Townson and his buddies.

“Because Romeo and Juliet died.”

This seemed too simple. Does death make it tragic? Sometimes death seemed the right answer, easier than life.

Click… clink.

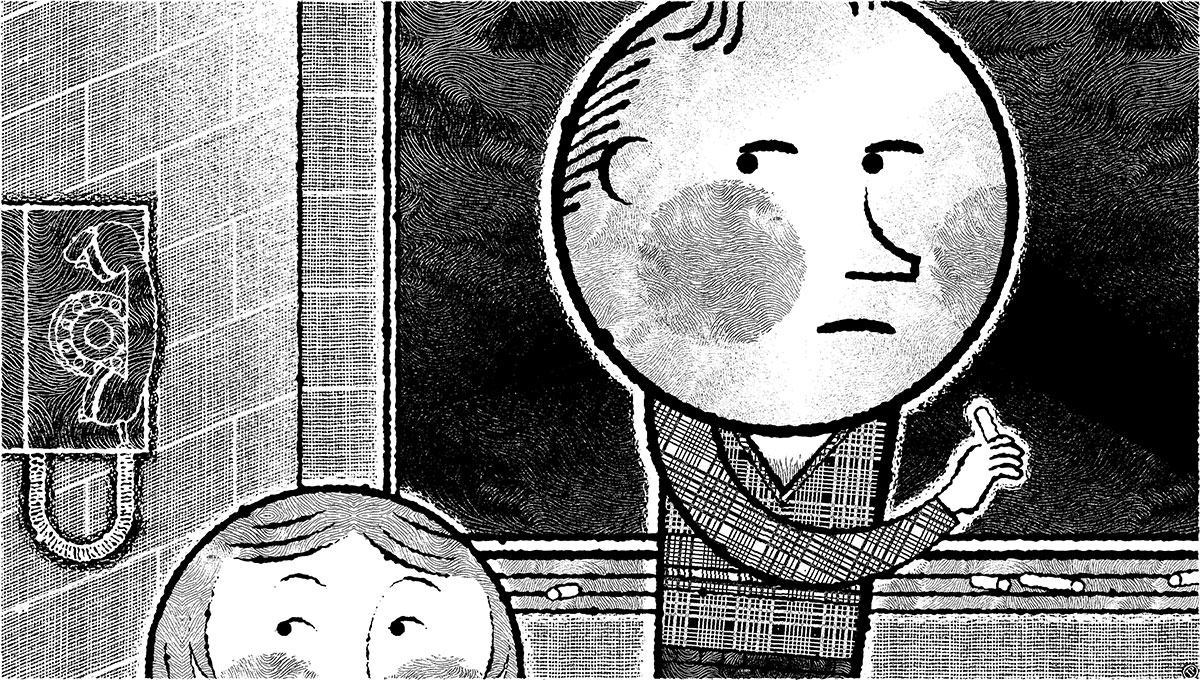

Mr. Alman looked up from the paper he was marking. Jenny could tell he recognized the sound of the coins Bradley was rolling down the aisle from his seat at the back of the class. Throwing money at her. Pennies for the whore.

Jenny shook her head slightly at Mr. Alman, signaling him to ignore it.

Mr. Alman looked past Jenny at the window seats near the back, where a group of male students sat around Bradley Townson like a rugby scrum. The rest of the students were scattered throughout the room. The two female students, Sarah and Ashley, were seated by the bulletin board to the left of the door. Behind the two girls, the classroom veered into an “L” where the outline of a small stage, several chairs, and props could be seen in the unlit darkness.

Jenny watched Mr. Alman. She used to think her teacher was good-looking, for an older guy. He was in his late thirties, tall and slim, with light green eyes and butterscotch hair sheared short to the scalp. His lips barely covered big, white teeth. She used to see him last year when she was in Grade 9, smiling as he greeted students in the hall.

Mr. Alman stood up, smoothed his wool sweater over his corduroys, grabbed his chair, and plunked it down beside Jenny’s desk. He stared down the aisle at Bradley and his circle of friends, most of who played on the Kilmore Collegiate hockey team. Bradley, Jimmy, and Alan were all first liners, even though they were only juniors.

Jenny tried to act as if whatever Mr. Alman was doing had nothing to do with her, but she couldn’t help glancing over her shoulder. Jimmy and Alan and the rest of the guys were scrunched over their tests, avoiding Mr. Alman’s glance. Bradley lounged in his desk, his bulk overlapping the chair as if it were toddler furniture. He stared with flat brown eyes, the muscles in his temples working as he chewed a wad of gum. He pulled a coin from the pocket of his Kilmore Knights leather hockey jacket, showed it to Mr. Alman as if he were going to do a magic trick and placed it on the corner of his desk. Smirking, he pulled the test toward him.

It was just money being thrown at her, Jenny told herself.

Sometimes, at the end of class, a handful of scattered coppers surrounded her seat. After everyone had left, including Mr. Alman, Jenny would scout around and retrieve the pennies. She would throw the handful of change into the garbage as she exited the class, the coins sounding like pellet gun spray as they hit the metal container. She would go wash her hands, scrubbing them until her knuckles showed pink through the suds.

One time, Mr. Alman noticed the change under her desk, scooped up the money, looked at Bradley, and said with a smirk, “Thanks. I’ll use it this weekend.” Bradley’s expression went flat. There were no rolling pennies for a week after that.

It was worse outside the classroom. Bradley and his friends waited for her at her locker, hooting and grabbing themselves when they saw her, following her as she turned around, making sucking sounds and asking how much it cost for some head.

Sometimes, Bradley stepped in front of her as she descended the long staircase in front of the school, blocking her, while her mother peered over her steering wheel at the bottom of the sloping hill, wondering what was taking her so long.

So maybe it would only be rolling pennies today. At least she had Mr. Alman sitting beside her, watching out for her.

Jenny turned to Question 4: “How was Marlowe’s playwriting influenced by the environment (social, economic, religious) of the 17th century? ”

“It was a very Christian society,” Jenny wrote, and tucked a strand of blond hair behind her ear. She thought about the signs welcoming newcomers into the town of Kilmore: Green Valley Protestant, Kilmore Pentecostal Baptist, St. Theresa’s Catholic, Gillian’s United, and Good News Gospel—over ten churches for a town of eight thousand people. Usually, she didn’t mind going to Green Valley with her parents and little brother, but she was worried now that people at church might hear the rumours.

Jenny turned back to her test and continued writing. “So in plays like Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, evil is punished.”

Jenny paused. Was she bad? Is that why Bradley Townson picked on her? Punished her? Did she wear her clothes too tight? Was she really a whore?

She hadn’t even had a boyfriend this year. Or done any of the things he said she did.

But Jenny knew that Bradley sensed something the first day of drama class seven weeks ago. He knew that she wasn’t that smart. That she would be easy to pick on. That she wanted people to like her. That she was afraid.

Mr. Alman had tried to do something. If Jenny had known her teacher was going to tell the vice-principal, she never would have met with him after school. Mr. Alman made her repeat all the things that had been whispered in her ear, or scratched on her locker—words like “whore” and “slut” and “bitch.” He was so nice that Jenny showed him the drawing that had been left in her desk that she had been too afraid to remove. A girl with shoulder-length hair lay on her back smiling, as a guy with a big oval penis lay on top of her. To the right of the figures, five stick men waited in line.

She should have known better. Vice-principal Leedle told Mr. Townson, Bradley’s father. Mr. Townson was the head of boys’ physical education at the school. He was also the coach of the Kilmore Knights hockey team, the school team that had made it to the provincial championships three years in a row.

Everyone knew nobody messed with Mr. Townson, or with his son, the hockey champ. Everyone except Mr. Alman.

Jenny shook her head and looked down at her test paper. She continued her response to Question 4:

It was a very social environment. The kings and queens would listen to concerts or see a play. But not everyone thought plays were good. Some thought them dirty. Anyway, Marlowe and Shakespeare wrote mostly about wealthy people and earls and kings in their plays.

Some of the girls thought she was dirty now too. Her friends she had known from Pleasantview Elementary School, the school her brother went to now, peeled away from her as soon as they saw Brad’s gang coming down the hall. They tried to be helpful at first. But even Calli, her best friend, began to phone her less, and sometimes avoided her at lunch. Jenny worried that Rosa, Kathy, and Calli believed the rumours. They said they didn’t, but who knew. Now they said hi to Jenny in the hall and maybe sat with her once or twice a week at lunch. Jenny was too scared to complain, in case they abandoned her completely.

Mr. Alman coughed. Jenny looked up. Mr. Alman’s right elbow almost touched the crooked elbow of her writing hand. She scraped her chair to the left. Mr. Alman glanced at the increased space between them.

Jenny tried not to be grossed out by Mr. Alman. At first, she didn’t believe what everyone was saying—that he lived with a man over in Bainbridge. That he had been seen shopping in the IGA with his boyfriend over the March break. She pictured Mr. Alman leaning over and kissing this man, sticking his tongue in the man’s mouth, and she knew, without even having to ask God, or her mother, that it was wrong.

He was the only one who knew what was going on and didn’t ignore it or laugh or think she must be a slut. But he was a homosexual. If everyone thought she was dirty, then what was Mr. Alman? A man who liked it up the bum.

“Fifteen more minutes, everyone,” Mr. Alman called out. The class shifted in their seats. Mr. Alman smiled at Jenny and she looked quickly back at her test.

He tried to make Jenny tell her parents about Bradley and his friends, even before he went to the vice-principal; to get her parents to phone the Townsons. Or talk to the principal, Mr. Handsel.

Then, two weeks ago, Mr. Alman phoned home and spoke with her mother. Jenny spent an hour explaining to her mom that Mr. Alman was concerned because there were only three girls in the drama class. That he just worried a lot. The guys liked to tease her, but it was for fun. Just like when her brother, Paul, bugged her.

She was so mad at Mr. Alman that she didn’t go to school that Thursday or Friday, telling her mom that she had period cramps. She lounged in bed listening to Madonna, playing with their dog, Rufus, and making a 3-D puzzle of a castle with her brother. Jenny’s mom liked her around because Jenny could help with dinner and take care of Paul if her mom had to go see one of her clients. Her mom did the accounting books for some of the farmers in the area. Her dad was away in town all day, working in the municipal utilities office.

Jenny did go back to school when she heard about the graffiti. Calli phoned her that weekend to tell her about the words spray-painted across one of the red-bricked walls of the gym. Last Monday, Jenny sidetracked around the left side of the school, following the path made by smokers, to see it herself. In thick red letters, each three feet high, were the words “FAGGOTS GO TO HELL!”

Jenny looked up at the clock. Ten after one. She had to stop daydreaming. She had five minutes left to finish the test. She looked around the class and saw Bradley staring at her. After several seconds, she heard the familiar click… clink as a penny hit her chair leg. She flipped through her test, looking for blanks, trying to block out the image of Bradley and his friends.

Drama class seemed a bit better the week after the test. Maybe it was because everyone was working on their independent projects, so students got to go to the library or the computer lab or the seminar room. Or maybe because they had a few days that were above freezing that hinted at an early spring. Jenny made sure she stayed with Mr. Alman, wherever he went. He liked her project on masks and masquerades. She was going to make a mask at home out of papier mâché for her presentation and paint it black, like the masks they used in Restoration drama.

On Friday of that week, Mr. Alman returned their tests and gave them their mid-term report card marks. As Mr. Alman distributed the tests, Jenny could hear male voices swearing. It sounded like Alan and Bradley’s voices.

“O.K.,” Mr. Alman began, “so, there were some good tests”—he looked at Jenny—“and some not-so-good tests. I also wrote your report card mark on the bottom of the first page. The report cards will be mailed home to your parents in two weeks time, on April 12th. The breakdown is as you see here.” Mr. Alman pointed to the chalkboard behind him: “Two tests, three assignments, participation, and homework.”

Jenny felt someone beside her.

“What the hell is this? ” Bradley asked. He stood in front of Mr. Alman’s desk, almost slapping Mr. Alman in the chest with his paper. Mr. Alman leaned away and then straightened up.

“Pardon me? ” Mr. Alman said.

“You failed me. You went and God-damn failed me.”

“If you want to talk about your mark, see me after class.”

“I want to talk about it now.”

“Now is not the time.”

“Why? Can’t you just tell me why you failed me? ”

“You mean why you failed.”

“Whatever.”

“I’d prefer to discuss it privately.”

“How about if I don’t want to meet you in private? ”

Mr. Alman paused. A few snickers could be heard around the room. Mr. Alman crossed his arms and leaned back on his heels.

“O.K., fine. Bradley, you obviously didn’t study or read the plays. You missed several questions completely, and many of your other answers were either too brief or incorrect.”

“Aw, c’mon. Have another look.”

“Why? Did I add up anything wrong? ”

“Maybe you did.”

Mr. Alman took the test and flipped the pages quickly, his lips moving slightly as he counted. Everybody in the class was silent.

“Seventeen out of fifty. That’s the mark.” Mr. Alman handed the test back to Bradley.

“Look at it again.”

“No.”

“I can’t fail the test.”

“Well, then maybe you should have studied. Now go sit down.”

“You don’t understand, Mr. Alman,” Bradley said as he leaned forward, smiling, as if he were going to invite Mr. Alman to watch him play hockey. “I can’t fail.”

“Then I suggest you study next time.”

“I mean, I can’t have a failing mark on the report card.”

“Well, do the work and I’m sure you can pass the course.”

Bradley moved over so that his six foot two frame blocked his friends’ view of the teacher. He looked at Mr. Alman and lowered his voice: “The hockey scouts don’t look at players who fail mid-terms. Even if it’s only one course. Not even if their stats are great.

“So…” Bradley dropped the test gently back on Mr. Alman’s desk and smiled, “have another look.”

“I’ve told you. I’ve seen all I need to see.”

“C’mon.

“Sit down, Bradley.”

“Sir—”

“I said sit down.”

“You sit down,” Bradley roared, causing Jenny and several other students to jump in their seats, “and take out your marks”—here Bradley grabbed the papers on Mr. Alman’s desk and shoved them at the teacher—“and have another look.”

Mr. Alman didn’t move.

“For Christ’s sake, look at it.”

“That’s enough,” said Mr. Alman.

“Listen, you fuckin’ queer, you’re gonna have another look, got it? ”

Jenny wasn’t sure if it was she who gasped in the pause that followed, but she felt the class react behind her.

“Get out.” Mr. Alman’s mouth was so tightly closed a white ring formed around it.

“Not until you change my mark,” Bradley said.

Mr. Alman walked over to the house phone on the wall beside the door and dialed. The students’ heads turned in unison to watch him.

“Mr. Leedle. I need you to remove Bradley Townson from my class.”

Mr. Alman held the black phone rigidly, staring down at the floor. Jenny felt the edge of Bradley’s hockey jacket press against the side of her desk. She moved the black mask she had made to cover the “78” written in green ink at the top of her test.

“I can’t wait,” Mr. Alman continued, “I need you to do it right now.” He turned into the phone, his blue-shirted back toward the students.

“I will not relax or calm down. I want you, as my superior, to take this boy out of my class.”

After a few seconds, Mr. Alman slammed the phone down. He walked over to his desk, grabbed his book bag, agenda, and papers, and walked out the door.

The class was silent. Jenny had never been in the classroom without Mr. Alman. If she was early for class or if his desk was empty, she went to the girls’ washroom until she was sure he would be there.

“Stupid, fucking, homo faggot.” Bradley’s voice rang out over the classroom. He turned to face his friends. “I’m gonna stick my fist up his fucking ass so high he’ll burp it out.”

“He might like it,” said Alan’s voice. There were a few relieved chuckles from around the room.

Jenny could feel people shift in their seats. A minute passed. Nobody came from the office. Not even the vice-principal or another teacher. Several students started zipping up their binders and knapsacks. The two girls got up in unison and slid out of the door. Everyone else started to move too.

Jenny stood up. She felt, rather than saw, Bradley turn to her.

“And what is the littlest ho doing? ”

Jenny unwrapped her coat off the back of the chair and shoved her arms into it; she picked up her knapsack with her left hand and her test and mask with her right hand and quickly walked towards the door.

A hand grabbed the back of her down jacket.

“Hey, not so fast.”

Jenny swung around, trying to get free of Bradley’s grip. She could see his friends gather their stuff and start moving towards her.

“Don’t.”

“Don’t what? Touch you? I thought you liked it.”

Jenny tried to back away toward the door. Bradley switched his grip from the back of her coat to her sleeve.

“Relax. I just want to ask you a question.”

Jenny tried to keep moving, but the paw of Bradley’s hand rooted her to the spot.

“Got a key? ”

“What? ”

“Do you got a key? ”

Jenny’s mind raced. To her house? Was he going to try to break in?

“I said, do you got a key on you… a house key, locker key, whatever.”

Jenny let herself nod.

“Good. Then I got something for you.”

He handed Jenny a piece of folded paper.

“You’ll know what to do with it.” Bradley let go of her jacket and Jenny staggered back several steps.

Bradley turned to Alan, who was now beside him. “I’m gonna go find my dad.”

No one was left in class. Jenny uncrumpled the piece of paper. On it was scrawled “ACCK 015.” It looked like a licence plate number.

The next day, Jenny stuffed one of her mom’s old parkas into her knapsack. It had a muggy, dog smell from Rufus. She made sure she was late, waiting with her brother at the bus stop in front of the Andersons’, plodding the two miles to Kilmore Collegiate with her scarf wrapped around her face to protect her from the wind. By the time she arrived at school, the buses had come and gone with their loads of students. She waited until it was one minute before the national anthem, when everyone would be scrambling to class.

She rounded the right side of the school into the parking lot, glancing up at the windowless bricked wall. She looked over the large expanse of the school parking lot. The day was cold, but bright, the morning sun glinting off the checkerboard of car hoods. Jenny walked behind a row of cars where the staff usually parked, squinting beneath the fake fur trim of her hood, scanning the slush-splashed license plates.

Jenny moved closer to a car and then knelt behind it. She took out the piece of paper Bradley had given her yesterday and checked it against the licence plate. She unzipped her knapsack and took out her black papier-mâché mask. She had taken elastic from her mother’s sewing kit last night and tied it through small holes she had bored on either side of the mask. She pulled the mask over her face, the material cold and stiff, and snapped the elastic around the back of her head.

She fished in her left pocket for the key. She had made sure to wear her leather gloves that had a good grip. Still squatting, she pressed the key along the side of the car and started to move, the scratch line beginning thinly and getting fatter as her pressure became consistent. She squat-walked around the car to the front, little pearls of white paint sticking to the edge of her key, and began work on the other side. She finished quickly, shoved the key in her pocket, and squat-walked between the cars all the way back to the side of the school.

She took off her mask and shoved it into her knapsack. The wind felt cold against the layer of sweat on her face. She unzipped the parka, rolled it into a ball, and stuffed it into the metal garbage container bolted to the ground. She walked around to the front entrance and went to her first-period gym class. She spent most of the class on the bench, pretending that she had forgotten her gym clothes, making intermittent trips to the bathroom to throw up until she was retching only air.

She skipped drama class that day and the next. She couldn’t face Mr. Alman after what she had done to his car. Or Bradley. It didn’t matter though, because Mr. Alman wasn’t at school either day.

On Wednesday, Jenny was called out from her volleyball game during gym class and asked to report to Mr. Leedle’s office. Jenny walked slowly down the hall, her knapsack hung over one shoulder, the sweat on her back cooling in the frigid air of the hallway.

The attendance secretary motioned her into Mr. Leedle’s office. As she entered, Mr. Alman turned and smiled at her. Jenny, startled, tried to smile back. Beside him was a uniformed Ontario Provincial Police officer and a man in a business suit with an attaché case. On the other side of Mr. Alman, Jenny recognized Mr. Leedle and Mr. Handsel, the principal.

The man with the attaché case said, “My client,” he indicated Mr. Alman, “and I will be in Mr. Handsel’s office.” He looked over at the police officer. “Can we get a copy of the statement as soon as it is available? ”

The police officer nodded, and checked his breast pocket for a pen. Jenny wondered if he would arrest her right there in her gym shorts. Or take her out in handcuffs, like they did with Jason McGuire when he was caught dealing drugs at the school.

Jenny sat down and felt the bare flesh of her legs stick to the chair. She placed her knapsack on her lap for warmth. As she grabbed it, her fingers touched something hard and lumpy inside: her mask. Mr. Handsel cleared his throat and introduced everybody, including Sergeant Whakefield from the Kilmore-Bainbridge O.P.P. detachment. Jenny looked up for each introduction, then kept her eyes on the carpeted floor. She wondered if they had called her parents.

“Tell us what happened in class the other day, Jenny,” Mr. Leedle said from behind the desk. He was balding, with long tufts of side hair Brylcreemed back to give the illusion of hair. Despite his rodent-like appearance, everyone knew he was the one who ran the school, not Mr. Handsel. And you wanted to stay on Mr. Leedle’s good side, like all the jocks did.

“What do you mean? ” Jenny was sure that they were going to ask her about the car.

“On Friday. In your drama class.” Jenny tried to capture last week in her mind, but it was like a television screen that was all fuzzy and white.

“The usual stuff.”

“Like what? ” Sergeant Whakefield interjected.

Jenny shifted in her seat and felt her mask again.

“We’re doing projects.”

“What else? ” Mr. Handsel encouraged, smiling at her.

Jenny tried to smile back. Mr. Handsel was supposed to be nice. She looked behind Mr. Handsel at the shelves of books covering the wall. She scanned the titles she could read from her seat: Fire Drill Procedures, Anti-Racist Education, Safe Schools, The Grade 10 Literacy Test.

“Mr. Alman gave back a test.”

“Do you know the student Bradley Townson? ” Sergeant Whakefield said, his pen poised over his notepad.

Jenny nodded, her eyes no higher than his bulletproof vest.

“Do you remember a conversation that Bradley had with Mr. Alman in class on Friday? ” Sergeant Whakefield asked.

Jenny remained quiet.

“They were talking about marks.”

Jenny thought of the green “78” on the top of her test.

“Did Bradley get his marks? ”

Jenny nodded.

“What did he say to Mr. Alman? ”

Jenny shrugged.

“Was Bradley mad? ”

“I guess so.”

“Why? ”

“I guess he didn’t like the mark,” Jenny commented.

“What else? ”

“That’s it.”

“What else was said? ”

“Nothing.”

“Jenny, we have ten other students who have given an account of that day,” Sergeant Whakefield said. “So, just tell us what happened.”

Jenny felt a whisper of relief. It wasn’t just her telling.

“I guess Bradley was a little mad. I don’t think he got a high mark.”

“What did Mr. Alman say? ”

“To stop talking to him that way.”

“Did Bradley say anything else? ”

“I don’t know. They were both mad.”

“Did he say something about Mr. Alman? ”

“Don’t lead her on, Sergeant,” Mr. Leedle said. “Only if she remembers something.”

Jenny didn’t know what to do. Did anyone else say that Bradley called Mr. Alman names? She was sure Bradley would squeal on her about the car if she said something. Or make her do something else to Mr. Alman.

Jenny looked up at the sergeant. “I don’t know.”

The sergeant gave a little snort. “Maybe you remember this.” He pulled out a piece of paper from a manila envelope. Jenny recognized the stick figures right away.

There was a knock on the door and Mr. Townson came in. There was a bit of a shuffle as Mr. Handsel and Sergeant Whakefield stood up, but not before Mr. Townson noticed Jenny. Bradley had exactly the same flat brown eyes as his father.

“Sorry about that. Just wanted to talk to Al and Arthur for a second. To get this thing with Brad cleared up. I can see you’re busy,” he looked at the principal and vice-principal. “So, I’ll catch you both later.”

He smiled around the room, looking at Jenny last before closing the door softly behind him.

Sergeant Whakefield slammed down into his seat.

“I don’t know that picture,” Jenny said quickly, before Sergeant Whakefield asked again.

“Mr. Alman said that you showed him this picture,” Sergeant Whakefield continued. “That some boys in your class were harassing you.”

Jenny couldn’t get Mr. Townson’s brown stare out of her mind.

“Mr. Alman has given a statement that you told him that several boys were calling you names, that they were sexually harassing you. That he has caught Bradley Townson throwing money at you. That you feel threatened by Bradley and some of the other boys in the class.”

“They’re just joking,” Jenny said through thin lips.

“He also said they are harassing him. In fact, I’m in here investigating a possible hate crime committed against Mr. Alman. The comments in the class on Friday and the graffiti on the gym wall. And the property damage that occurred to Mr. Alman’s car.”

Jenny felt an icy block lodge in her throat.

“So, if you have something to say, about comments and actions directed at you or at Peter Alman, by Bradley Townson or anybody else, it would be very helpful to get to the bottom of this.”

Jenny said nothing. The seconds ticked away. She looked over at Mr. Leedle for permission to leave. Mr. Leedle smiled and walked her out of the office.

Jenny grabbed her clothes from the gym, quickly changed, and walked home in the cold midday sun. She told her mom that she had been interviewed about problems in one of her classes between a student and a teacher. She didn’t know what they were talking about. She asked her mom to phone the school to tell them that she didn’t want to talk to anyone else, including the lawyer.

Calli phoned her after school while she was watching The Two Guys Animal Show with Paul. It was her brother’s favourite show.

“You wouldn’t believe it,” Calli said. “Mr. Alman called the cops on Bradley.”

“Really,” Jenny replied, trying to act surprised. “What for? ”

“You know. You’re in the class. Did Bradley really call Mr. Alman a fag? To his face? ” Calli giggled.

“Well, sorta,” Jenny giggled a bit too. Paul looked over at her. He began to imitate the monkey on the television, rocking in his seat on the coach.

“And you should see Mr. Townson. He just flipped out on Mr. Alman. Right in front of the office.”

“Wow.” Paul started climbing on the back of the couch toward her.

“Now Mr. Alman has some fancy human rights lawyer from Toronto.”

Jenny thought about the tall man with the attaché case.

“Rosa said that Mr. Alman refused to come back until Bradley was arrested or expelled or something.”

“Can he do that? ”

“I don’t know. Can you imagine? Mr. Townson would freak.”

Jenny tried not to think about the school getting rid of Bradley. What was the point in hoping? Paul jumped on her neck from behind, making monkey-screeching sounds, and Jenny dropped the phone.

“Sorry.”

“Anyway,” Calli continued, “Mr. Leedle wouldn’t let that happen. That’s for sure.” Mr. Leedle led the fundraising efforts for the hockey team every year. He also went to every game, even most of the away ones.

When Jenny got off the phone, she chased Paul around the room, tickling him until he screamed for their mom. As she wrestled with Paul, Jenny wondered what would happen if Mr. Alman left Kilmore. In some ways, it would be a relief. But what would happen to her drama class? Would they get a supply teacher in? Would Bradley still be there?

She could never go back to the class without Mr. Alman to protect her. But how could she go back anyway after what she did to him. What Bradley knew she did.

Jenny was lying on her bed on Friday night, relieved that the terrible week was over. She had gone to school the past two days, skipping drama of course, hiding in the library at lunch, worried that the office would call her down again, or phone home.

The telephone rang and she reached for it from her side table with the frilly white lamp.

“Turn on the game,” Calli ordered.

Jenny knew she meant hockey. Not only was hockey a town obsession, everyone knew that the boys’ competitive league, the Southern Ontario Hockey League, played Friday nights.

In elementary school, they used to get together at Calli’s or Jenny’s on Friday night and watch the game. Sometimes, they even went to McCarthy Arena when the local teams played in town, imagining going out with one of the older, sophisticated high-school boys. They talked about their favourite players as if they knew them, memorizing all their stats and arguing about who was the better player. Sometimes they got up enough guts to say hi to a player as he walked out of a dressing room, equipment bag in hand, hair wet from the shower.

She used to see Bradley Townson play. He was so good he always played with the older guys. With his flushed cheeks and the way he punched the air after each goal, she thought he was brave. And romantic.

She hadn’t watched a game in a long time.

Jenny walked over to her bureau and turned on the small television she inherited after her parents bought a new set for the living room.

“O.K., it’s on,” Jenny said into the phone as she sprawled on her bed. She watched the Oaklanders make a rush on goal.

“Just a minute. You’ll see it in a second.”

It looked like the other team was in blue and white. The Stampeders. Bradley’s team.

“There—look.”

Jenny squinted at the screen. The puck had gone up over the glass. They were panning the crowd, and Jenny saw some people in the seats holding a banner. She could make out the word hate and the tail end of a word ending in -ment. The camera swung back to the ice and the faceoff in the Stampeders’ end.

“So? “ Jenny asked.

“Did you read it? ” Calli asked.

“Parts of it.”

“Can you believe Mr. Alman? ”

“What do you mean? ”

“To print that stuff about Bradley.”

“Mr. Alman is at the game? ”

“Yeah. There are a whole bunch of men taking turns holding the sign. I bet you they’re all gay guys from Toronto. I bet you one of them is Mr. Alman’s boyfriend.”

“Mr. Alman is holding a sign about Bradley? ”

“It says—wait a sec, I wrote it down—it says, ‘HATE CRIMES AND HARASSMENT DO NOT BELONG IN SCHOOLS. EXPEL BRADLEY TOWNSON.’”

“Oh, my God.” Jenny put her hand over her face.

On Sunday night, Jenny still hadn’t decided if she was going to go to school the next day. She went out back with the dog, walking into the velvety darkness until she reached the light by the shed that frosted the blanket of snow in their yard. Beyond the circle of the light was the shadowy edge of the trees that populated the rest of the ten acres. Jenny plodded around in the snow in her stained Sorel boots, wrapping her father’s old plaid fleece jacket tightly around her torso, waiting for Rufus to pee.

Jenny heard Rufus barking and she realized he had already gone back to the front of the house. She started back, worried that the dog might run onto the road if he saw something to chase. As she came parallel to the side of the house, Bradley Townson walked toward her with Rufus jumping at his side.

Jenny stopped.

“Hi,” Bradley said smiling.

Jenny looked around. Bradley was blocking her way to the entrance at the front of the house and she wouldn’t be able to run very fast in the deep waves of snow in the yard.

Bradley shuffled his big frame from one foot to the other, stamping down the snow. Rufus bounced over to Jenny, and back to Bradley, tail wagging.

“I was wondering if they talked to you about Alman? ” He seemed subdued, almost polite.

She looked at him. Jenny thought about lying, but remembered Mr. Townson’s eyes looking at her.

She nodded.

“He’s making trouble for me.”

Jenny thought about the banner at the game, the red words. She thought about the graffiti on the gym wall that still hadn’t been removed.

“I need you to do me a favour.”

Jenny looked at him.

“Tell Mr. Leedle that Alman was bothering you.”

Bradley bent down and scratched Rufus behind the ears, and continued talking without looking at her.

“Bothering you, like touching you, phoning you, talking to you after school, whatever you want to say.”

They stood there for a few moments, as the dog ran back and forth between them.

“Nice place your parents have here,” Bradley said, looking around. He spied Paul’s hockey net shoved against the cement wall of the house, green plastic hockey sticks hanging over the top of the goalie net.

“You have a brother? ”

Jenny nodded.

“What’s his name? ”

Jenny hesitated. “Paul.”

“What school does he go to? ”

Several seconds ticked by. “Pleasant-view.”

“I got a cousin who goes there. ”

Bradley gave Rufus one last pat before he turned around and walked the smeared path of mud and slush back to the front of the house. Jenny heard a car engine sputter and start. The twin-beam headlights travelled over the snow and struck her face, whitewashing it into a mask, before moving past her through the trees as the car sped away.