Tradition meets modernity head-on at Coach House Books, where book publishing is being reinvented for the twenty-first century. In an old coach house on bpNichol Lane, nestled between St. George and Huron streets, the staff of the publishing/printing house straddle the past and the future. While the age-old smell of ink fills the air, the worn floorboards, scuffed after many years of wear, creak under the weight of Doc Martens and high-tech computers.

Welcome to the newest stage in book publishing, where “E-book” is a common expression and the bound paper package that we call a book is referred to as a “fetish object.”

“This is a business that has been created over hundreds of years,” says Hilary Clark, the press’s managing editor. “It’s a model that is well established and we are bucking a lot of trends.”

Coach House is taking advantage of the Internet, using its services as the basis for its publishing operation. But while the house is experimenting with a new medium, it also remains rooted in the past.

This new addition to the Canadian small-press industry came onto the scene a year ago. Coach House Books rose from the ashes of Coach House Press, which closed its doors in the summer of 1996, some say as a result of drastic reduction in provincial government funding, while others blame a too-rapid expansion. The old press, which separated from Coach House Printing in 1990, was created by a group of friend who loved books and had a mandate to publish new and experimental writers—writers who wouldn’t necessarily produce a bestselling novel or collection of poetry. As a result, many of Canada’s big-name writers of today—Michael Ondaatje, Anne Michaels, Margaret Atwood—published early works at Coach House Press.

Located again in its original building, the new Coach House Books is, according to Clark, similarly run by a “few old friends,” and plans to carry on the legacy and publish the new and experimental writers of today for a specialized audience.

But there is a distinctly new feel about Coach House Books. For one thing, the staff is a combination of the older crowd who originally founded the press in the mid-nineteen-sixties and younger people like Clark.

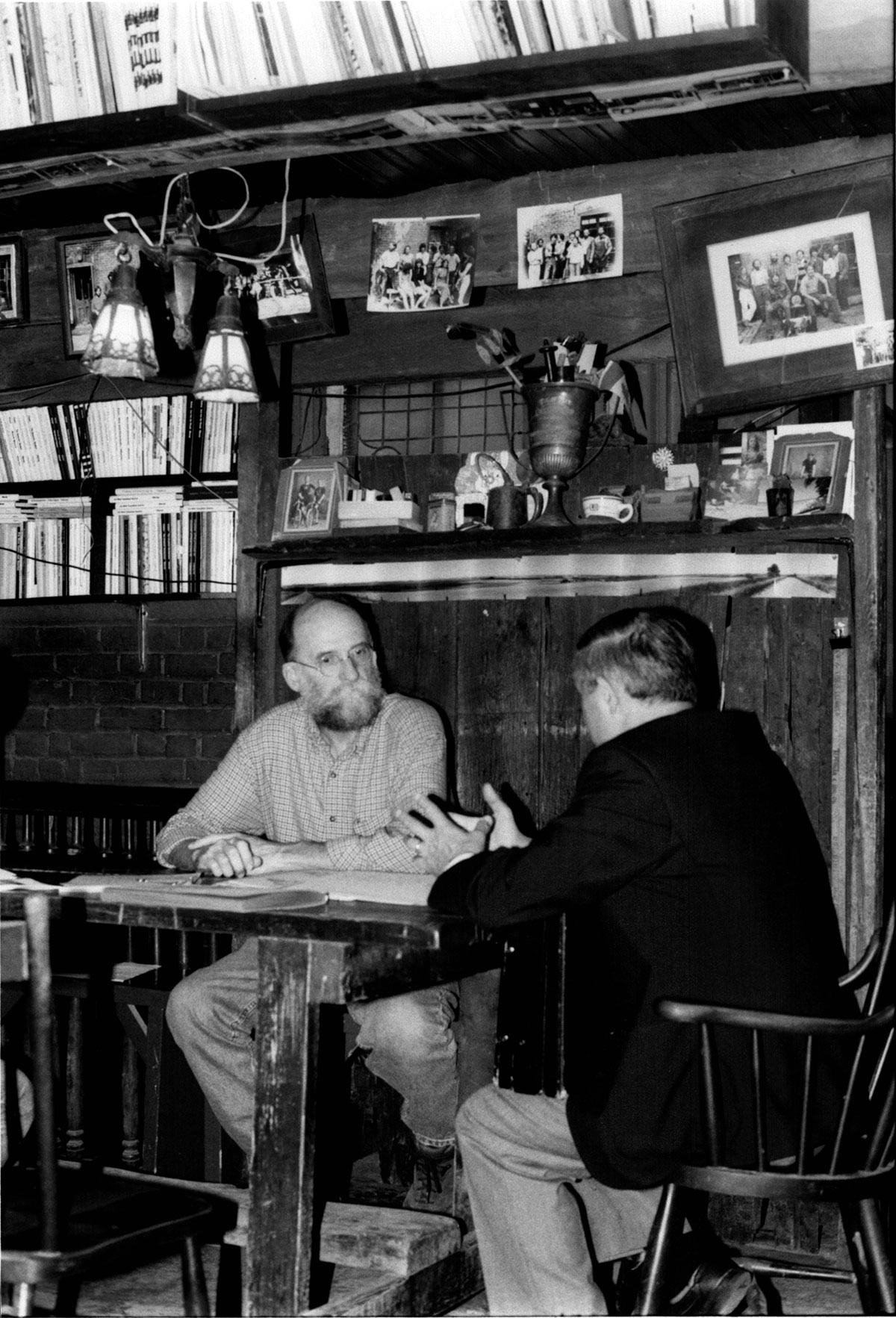

“We’re avant-garde when this is a generation of older people reconnecting with the younger people,” says Stan Bevington, Coach House’s publisher, who orchestrated the comeback.

The obstacles faced are avant-garde too. Recently, Coach House has been having problems with its Internet server—which wouldn’t normally be a problem for a publishing house, unless its main operations are on the World Wide Web. Which, in this case, they are.

With an eye on the Internet, Coach House Books has decided to back out of the distribution business and print small runs of only fifty to three hundred books. Instead, it is peddling its books on the Web. This means that to read a Coach House book one can simply call up chbooks.com and read the text off a computer screen. There is a selection of E-books, including poetry, and even a comic book. And taking full advantage of the multi-media potential of the Web, there are animated poems along with sound effects.

But by placing books on-line, Coach House has had to find an innovative way to pay writers for their work. If people read poems for free off the Web, then the writer does not receive royalties. Bevington has solved this problem by creating a system where readers, out of the goodness of their hearts, can tip the writer. (As the site reminds you, “Tip the writer, not the waiter.”) An appropriate amount is suggested—ten per cent of the book’s sale price, which is about the same return the writer would receive from a hard copy of the book. To tip, all the reader has to do is key in the amount along with a credit card number. Tipping the writer has turned out to be a success since not only are people tipping, but they also are ordering copies of the books over the Internet because, according to Clark, “The people who read [a book] on-line also want it for their shelf.” This means Coach House will probably not have to abandon its Gutenberg-style publishing in favour of the E-book.

“The books will be made in beautiful hardcovers because people like beautiful hardcovers,” she says.

The advantage of the Internet is that it offers a small publisher access to an enormous audience for the price of a monthly Internet server. Through the Web, Coach House gets approximately three thousand hits a week from people in places as far away as Australia, Malaysia, and Israel. Recently, a man from the southern United States called Coach House, thrilled by what it was doing, and ordered several books, including a limited edition collectible worth more than one hundred and fifty dollars.

“This is a massive expanse that is usually only available to companies with massive ad budgets,” says Clark.

Bevington believes that when people catch on to what is available, the E-book will grow in popularity. He suggests that when people realize the potential of having the books on-line—reading the books you forgot at home on the office computer over lunch—that the Coach House Web site will get even more hits. As it stands, most of the on-line requests are for the electronic books.

“When you are doing something totally different, it takes a while for people to say, “So that’s what you’re doing,” explains Clark.

Where people seem to be catching on slowly is in the payment department. People are reluctant to use their credit cards on the Web because they feel it is not secure. Clark points out it is just as safe to give your credit card number to a waiter in a restaurant as it is to send it over the Internet. The transaction is encrypted, meaning that the only people who have access to the credit card number is the credit card company itself. Not even Coach House has access to the information.

Coach House is hoping to finance its Internet endeavor by spreading out over a variety of sources. They are hoping to raise funds through the sale of ordinary books as well as collectible ones, and by soliciting memberships. People can subscribe to Coach House for a fee and receive the company’s newsletter. However, the backbone of the business is the printing press that sits on the ground floor of the coach house, below the editors in the second-storey office. Not only do they print and bind their books, but they are also commissioned to print other publishers’ products. In this way Coach House Books can continue to do what it does best: publish specialized books for a specialized audience without having to give in to market pressures and publish what sells rather than what it likes. While Coach House is not reeling in money, it is staying true to its original focus.

“We’re not doing cookbooks,” says Clark of the ultimate moneymaker.

Speaking excitedly, Bevington professes that a principal reason Coach House reopened with the help of the Internet was due to his concern for accessibility. With an electronic book, someone who can’t otherwise read the text of a hard copy because the size of the print is too small can read it on Netscape by choosing to increase the size of the letters.

“We’re ardent about giving racy new literature to old folks on the Web,” he says.

E-books do not only offer reading through voice generators to the visually impaired, but also to those who are unable to hold a book.

“All our pages are designed so that they are friendly to these types of readers,” says Clark.

But it seems that at Coach House the editors don’t really mind who their readers are. They are not picky, they are simply driven to create good, beautiful books for whoever is interested in good, beautiful books.

“We just have a different vision,” says Clark.

The Internet is only another vehicle to get book out and enjoyed by as many people as possible. While Coach House forges ahead into the new world of publishing, it is reassuring that they are doing so not for personal profit, but rather for the sake of the books themselves. If critics condemn the E-book, favouring its not-so-ephemeral cousin, they cannot condemn the editors at Coach House because it seems they are doing what they do for nothing more than the love of books.