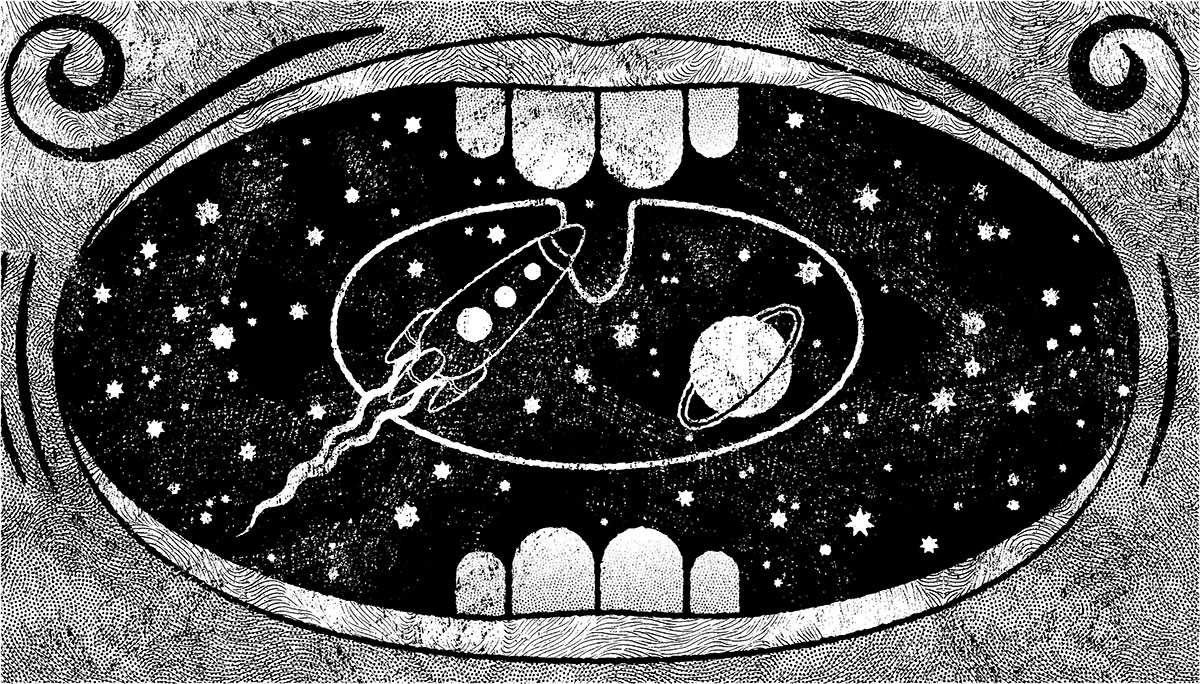

The doorbell rings and I open the door onto a bright sunny day. The mailman is standing on the porch and when I look into his mouth I see the universe. Snow-capped mountains, radishes, raindrops, Piccadilly Circus, storm clouds, lightning, India, floral dresses, beautiful limbs, archways, shipboard navigation systems, pipe cleaners, discarded frost-free refrigerators, sidewalks, fire, Louisiana, Teflon cookware, radiators, hardwood flooring, lemons, rain barrels, solar flares, Chicoutimi, bailiffs, portly saboteurs, dancing children, Mount Fujiyama, eternity, galvanized eavestroughs, manhole covers, binary stars, subway systems, waves, squids, discount stores, old people, pterodactyls, reticent rhythm-and-blues spokespeople, Tuscany, neglected deck chair manufacturers, neutrinos, Buxtehude deniers, disgruntled conservation-authority parking-lot attendants, monsoons, tsunamis, bicycles, uvula shadows, taste buds, and a hundred thousand stars like distant cavities in the vast black dental work of the sky.

“Can you please sign? ” the mailman says, holding up a clipboard. Planets are spinning where his tonsils should be. The bright blur of a comet streaks across his soft palate. In all this vastness, I feel certain that life exists. Surely we could not be alone in all this possibility. Cells or galaxies come into being behind his wisdom teeth. Signals are sent from earnest transmitters in his pharynx. “We are here,” the signals say. “We are not alone. We look for companionship in the incomprehensible massiveness of space.”

I feel sick. I am still in my pyjamas. I’ve only half eaten my breakfast and here is everything in the mouth of a mailman. His eyes are hopeful, plaintive beneath his blue cap. In his ordinary hands he holds a clipboard with my name printed below a list of what I take to be the names of living things. I hesitate. I don’t know what I would be committing myself to if I sign. “Who are you? ” I ask. “What is it you are asking of me? ”

As he opens his mouth to answer, I see whales, the future, carpeting, truth, suffering, and, between two teeth, there we are, the mailman and I standing on my porch in the bright morning. “I could use a shave,” I think to myself. “Who else has seen me like this? ” The mailman looks O.K. though, his tiny clipboard illuminated by stars. I see myself waving stupidly at my unshaven larger self standing outside the mailman’s cavernous mouth. It is as if I were on TV and were greeting my friends and family. Is this what Gandhi or Maimonides would do? Even Groucho would not have been so inane. “Hi, Mom!” he’d say. “Outside of the mailman, the universe is man’s best friend. Inside of a mailman, it’s too dark and sticky.” But I am beginning to suspect that this is not the normal mailman. In truth, I do not recognize him. Perhaps this is not his usual route and he is filling in for the regular guy.

I begin to speak but wonder what the mailman can see in my open mouth. Have I flossed recently? It has been a while since I brushed with diligence. I am willing to admit that perhaps my oral hygiene is not up to universal standards. My mouth is a vibrant organic place, an address not rich in highly developed life forms and advanced consciousness, but, nevertheless, a place where life may have a chance, where galaxies and solar systems could be born and eventually spawn the nimble feet of gazelles and the soul-scouring calls of owls heard amidst the complicated verse forms of creatures who have learned to mediate their conception of the world through a system involving the coordination of muscle contractions in their mouths and abdomens.

The mailman looks at me curiously. He is holding not only the clipboard but also a pen. It is a sure sign that I have some breakfast caught between my teeth. He is offering me implements that would be helpful in the removal of items foreign to my dentation. The clipboard is a possibility but the pen will be more effective. I take it from his hand. The mailman smiles and the universe disappears in his closed mouth.

I raise the pen to my mouth. The mailman looks pleadingly at me. I aim the pen tip at my teeth. I intend only to dislodge the breakfast fragment that has become trapped, but, as the pen comes close to my mouth, desire, like the tremendous gravitational pull of a gas giant, sucks me into its orbit and I push the entire pen into my mouth. There’s a flash of bright light and the shadow of vast interstellar darkness as the mailman again opens his mouth to speak. I begin to chew on the pen, feel the satisfying crunch of blue plastic, the juiciness of the ink as it spurts onto my plain human tongue, just a small red rectangle of inner-city backyard beside the borderless acres of the mailman’s cosmic maw. I taste the acrid nectar of the fossil glow as I swallow. I turn and go back inside my house. I will not need more breakfast.