On the evening of February 2, 1951, the Toronto Press Club welcomed guests to its third-floor premises, located atop a steep set of stairs at 99 Yonge Street, to celebrate the reopening of its ladies’ lounge. The club, then still known as the Toronto Men’s Press Club, was where the city’s newsmen met to drink and talk shop. Women were not offered membership until the nineteen-seventies, though the lounge, where wives and other female visitors congregated, was an early concession. The renovated room was spacious, with high ceilings. A dark panelling ran along the lower portion of its walls, and the furniture was tastefully modern. Barbara Ann Scott, the twenty-two-year-old Olympic figure skating champion, known as Canada’s Sweetheart, was in attendance to untie the inaugural ribbon, while Viscount Alexander of Tunis, King George VI’s charismatic and popular Governor General and himself an active club member, smiled and mingled alongside a who’s who of local newspaper men, including the Toronto Telegram columnist Ted (the Moaner) Reeve and Jim Vipond, the sports editor of the Globe and Mail. Barkers and pitchmen from the Conklin carnival provided the evening’s entertainment.

Most eyes that night were drawn to a mural that covered not only the room’s walls, floor to ceiling, but also the ceiling itself, as well as the doors, moulding, and air vents. The elaborate work depicted the evolution of the fourth estate, from the Stone Age to the present day. Vignettes included a friar, possibly Martin Luther, nailing a public notice to a poll, a reporter chasing a nineteenth-century fire engine, a pool of switchboard operators, and a group of members mobbing the club’s own bar to buy tickets to its annual By-Line Ball. Generic caricatures of newspaper staff—photo editor, slot man, sob sister—filled space between the ceiling’s decorative slats. The mural was the work of Lou Skuce, a short, stout man, often, by this time, referred to as Canada’s Greatest Cartoonist. Skuce began making a name for himself as a newspaper illustrator more than four decades earlier. He had a natural talent that allowed him to develop a loose, unstructured style, and possessed a wit that played well with the blue-collar middle class. “Lou was a horse for work,” the Telegram’s Reeve once said. “Nothing was too much trouble, no detail in his work too small for him to look after.”

Skuce was a champion athlete in his youth, but his trim frame had grown since into a rounder build that made him look jolly and lovable in his shirtsleeves yet suave and commanding in a suit. He retained a full shock of hair—once dark, now white—and his face was long, kind, and handsome. He often wore spats and smelled of cigars, which he tended to ash on his vest. Skuce was outgoing, well liked, and extremely generous. He was deeply religious, continuing his family’s Anglican tradition, but stressed that the annual month-long orange juice fast he undertook later in life was simply for the purpose of keeping his weight under control. By 1951, Skuce had contributed directly to many of the major—and minor—daily, weekly, and monthly publications in Canada, and was one of the industry’s most beloved figures. “Through the tireless efforts and artistic ability of Mr. Skuce,” Frank Teskey, the press club’s president, told the assembled crowd on the night of the ladies’ lounge rechristening, “the Toronto Men’s Press Club now possesses an invaluable special feature which might well be the envy of any newspaper club in the world.”

Skuce was working in his father’s blacksmith shop, in the village of Britannia, when, not long after the turn of the twentieth century, he began drawing cartoons for the Dipper, a small weekly newspaper based in nearby Ottawa. Newspapers began using illustrators and cartoonists in the eighteen-nineties to alleviate the greyness of their pages, and by the time Skuce’s career began, editorial cartoonists were a vital, popular, and respected part of the industry. His work on the Dipper soon caught the attention of the larger Ottawa Evening Journal—a right-leaning daily broadsheet with a more rural readership than the competing Citizen—which hired Skuce away. While on assignment in the House of Commons for his new employer, Skuce pestered the press-weary Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier so much that Laurier assigned a young member of Parliament to assist him. “I’ll leave you with Willie, here,” Laurier said, as he introduced Skuce to the future prime minster William Lyon Mackenzie King, then the deputy minister of Labour. “Willie is a good boy and a clever boy. You listen to Willie and he’ll explain things to you.”

In 1909, Skuce accepted a job as the featured cartoonist and art editor of the Toronto World’s Sunday edition. The Sunday World was unique in Canada. American newspapers published their leisurely weekend read on Sunday, but stricter Canadian laws prevented business transactions from occurring on the Sabbath. As a result, papers such as the Globe, Mail, and Star printed their more lavish editions on Saturday. Many American Sunday editions were populist, secular reads, with entertainment coverage and a selection of content aimed specifically at women. Canadian papers like the Saturday Globe often were more traditionally nationalistic and Christian in tone, publishing book reviews and halftone photographs in contrast to the colour comics and sensational illustrations preferred by many of their U.S. counterparts. The Toronto Sunday World—published on Saturday—took advantage of an unfilled niche, creating a Canadian version of the American metropolitan weekend paper, aimed more at the middle class than what was being produced by its highbrow competition.

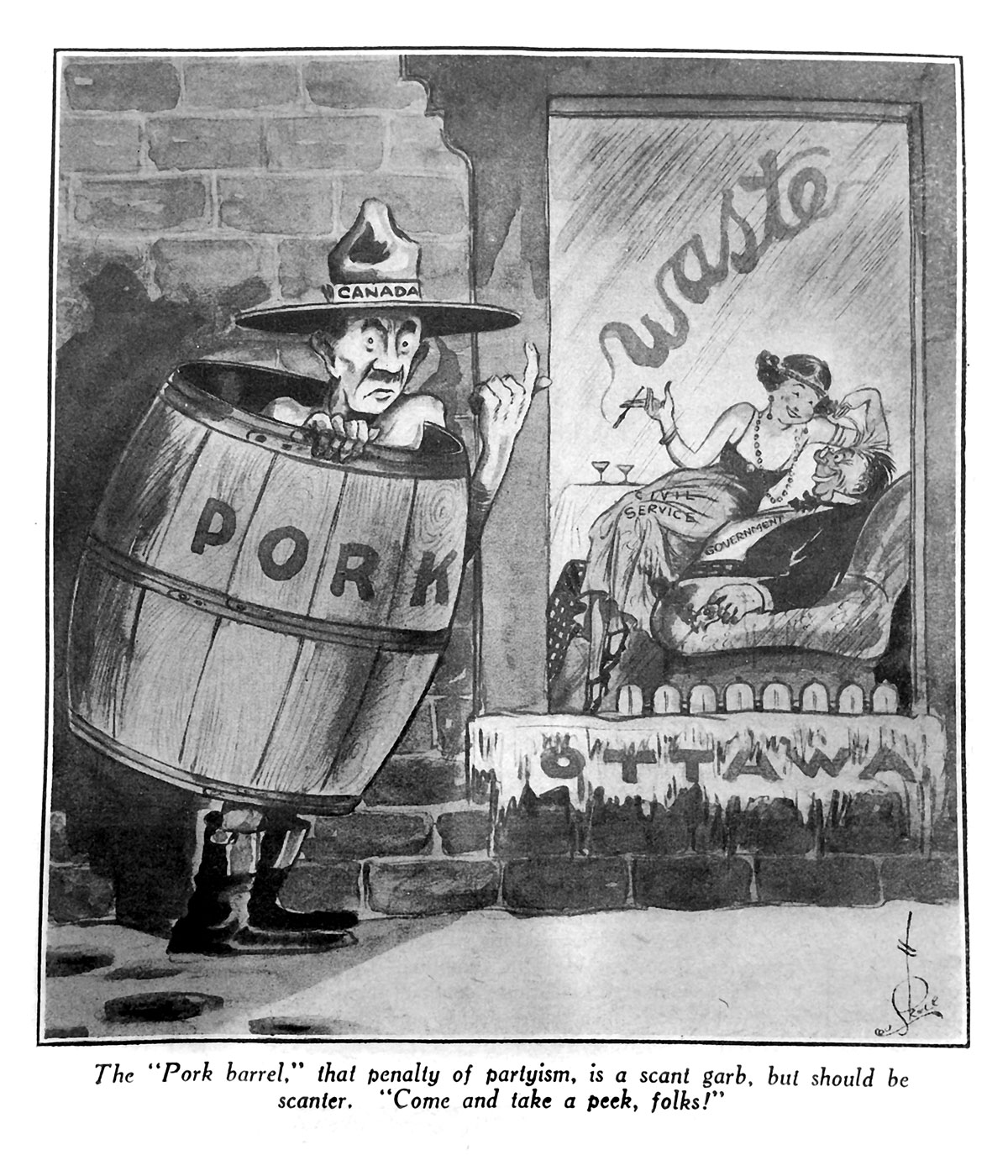

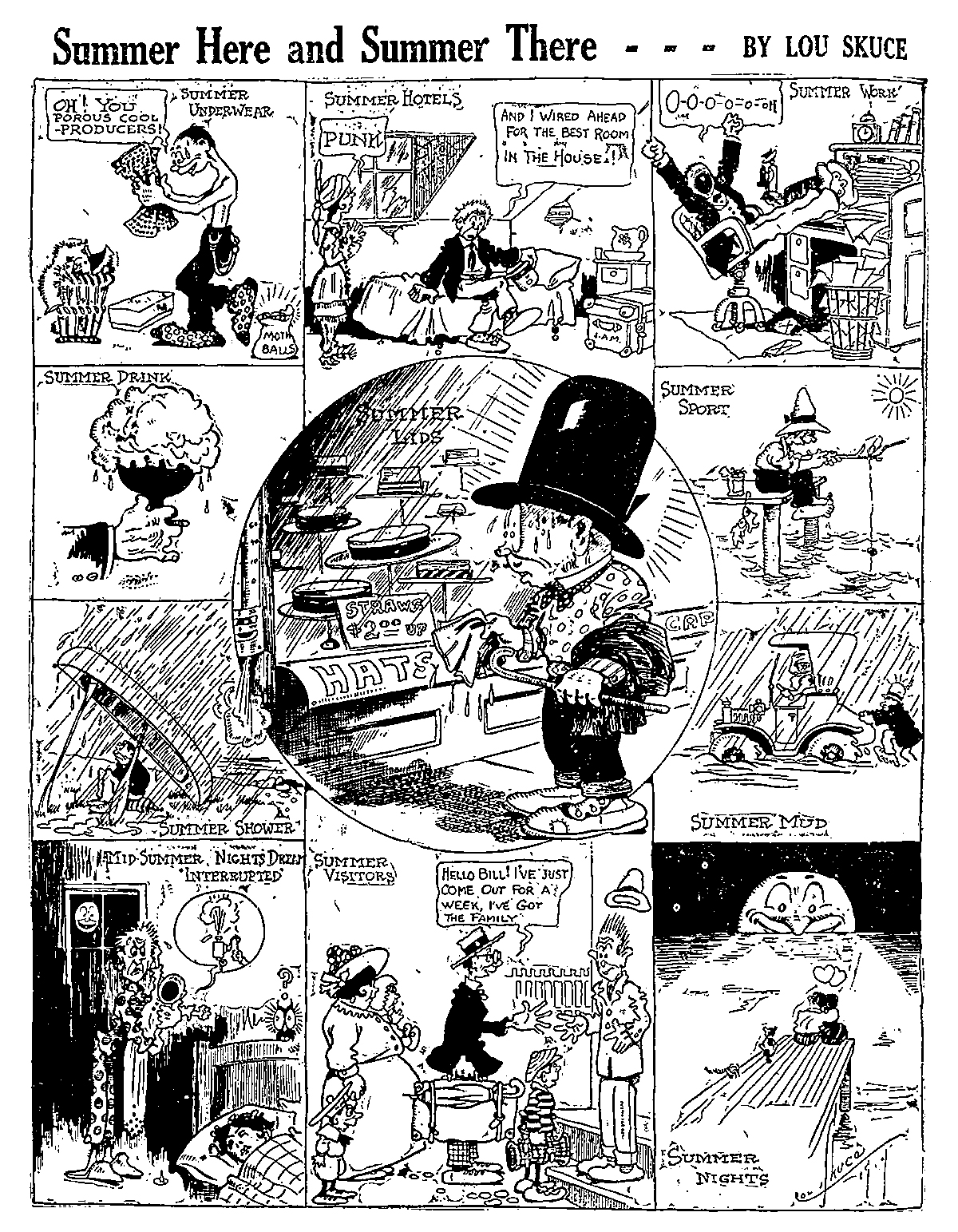

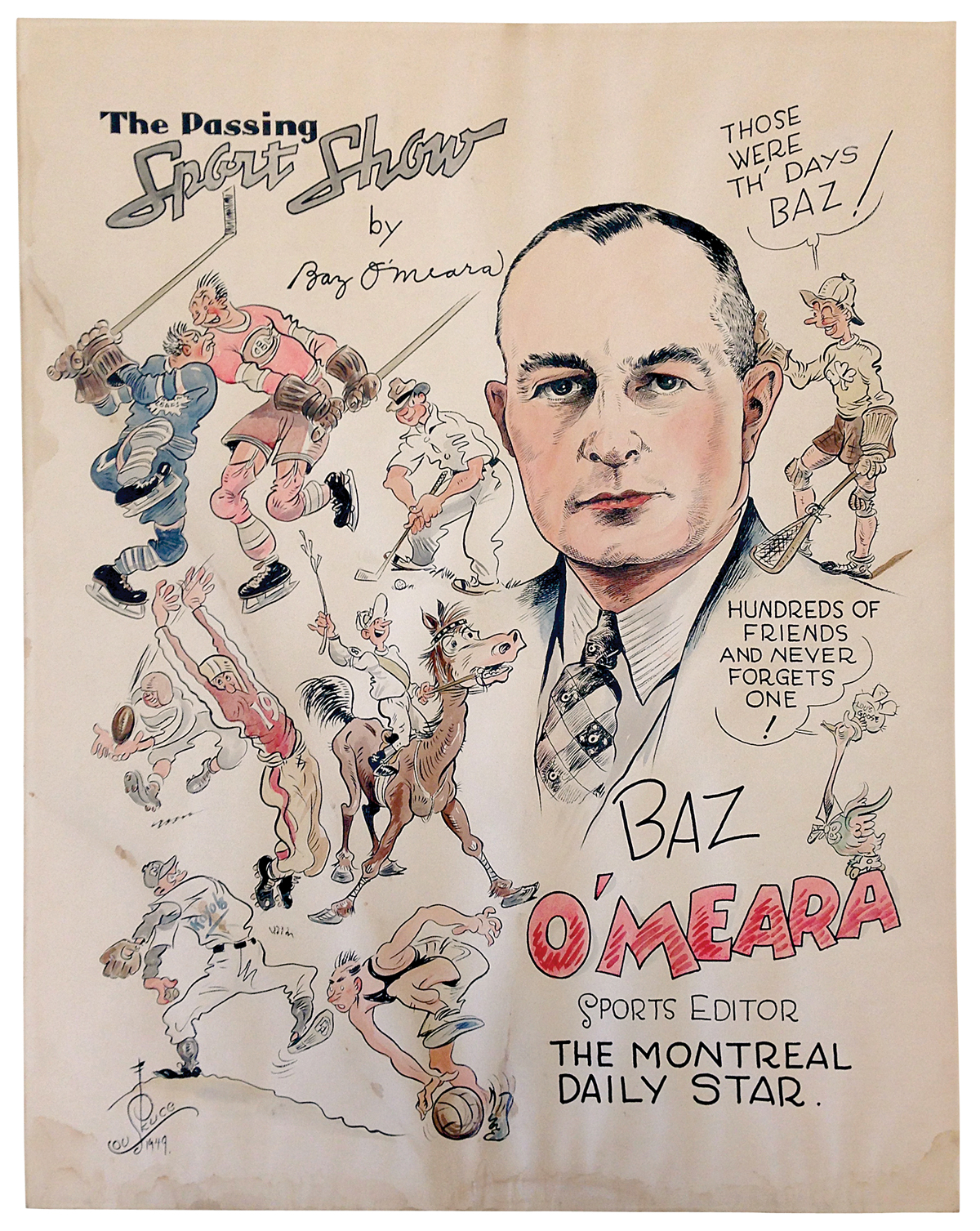

Skuce’s earliest drawings for the World had an accomplished but traditional style that quickly gave way to full on caricature and a general cartoonishness, much in the vein of his contemporaries A. G. Racey, of the Montreal Star, and, especially, Jimmie Frise, the creator of the popular Anytown, Canada, comic Birdseye Center. Skuce’s cartoons were visually frenetic and fun, with a sense of humour that played directly to the World’s intended audience and soon made him a household name. “Skuce says the secret of his success is action in the drawings,” said a reporter profiling the artist, “but . . . it is the merry way in which Skuce laughs with us, not at us, that has such a wide appeal.” Each Sunday Skuce drew Events of the Week in Cartoon, a strip of five single-panel editorial cartoons that tidily summed up recent news items or offered witty, light criticism on subjects as serious as politics or as banal as the weather. Skuce contributed a similar weekly roundup, titled How It Looks To Us, to the sports section, while other strips—including Things To Worry About, War Terms Explained, and XSkuce Me—were more fluid, coming and going as they outlived their usefulness.

Skuce once asked Billy Armstrong, the World’s handicapper, for a tip on the coming Saturday’s horse race, which he incorporated cryptically into a comic—a trick popularized years earlier by Clare Briggs in his short-lived A. Piker Clerk, and later taken up by Bud Fisher in what eventually became the strip Mutt and Jeff. Armstrong’s tip paid off, and Skuce continued the gag. Decades later, the Globe and Mail columnist J. V. McAree recalled that readers continued to use the sports page comics as a race card long after Skuce had moved on. Readers’ “ingenuity in finding imaginary clues was extraordinary,” McAree wrote. “On the whole they probably did a little better than when they were looking to Lou and Billy for guidance.”

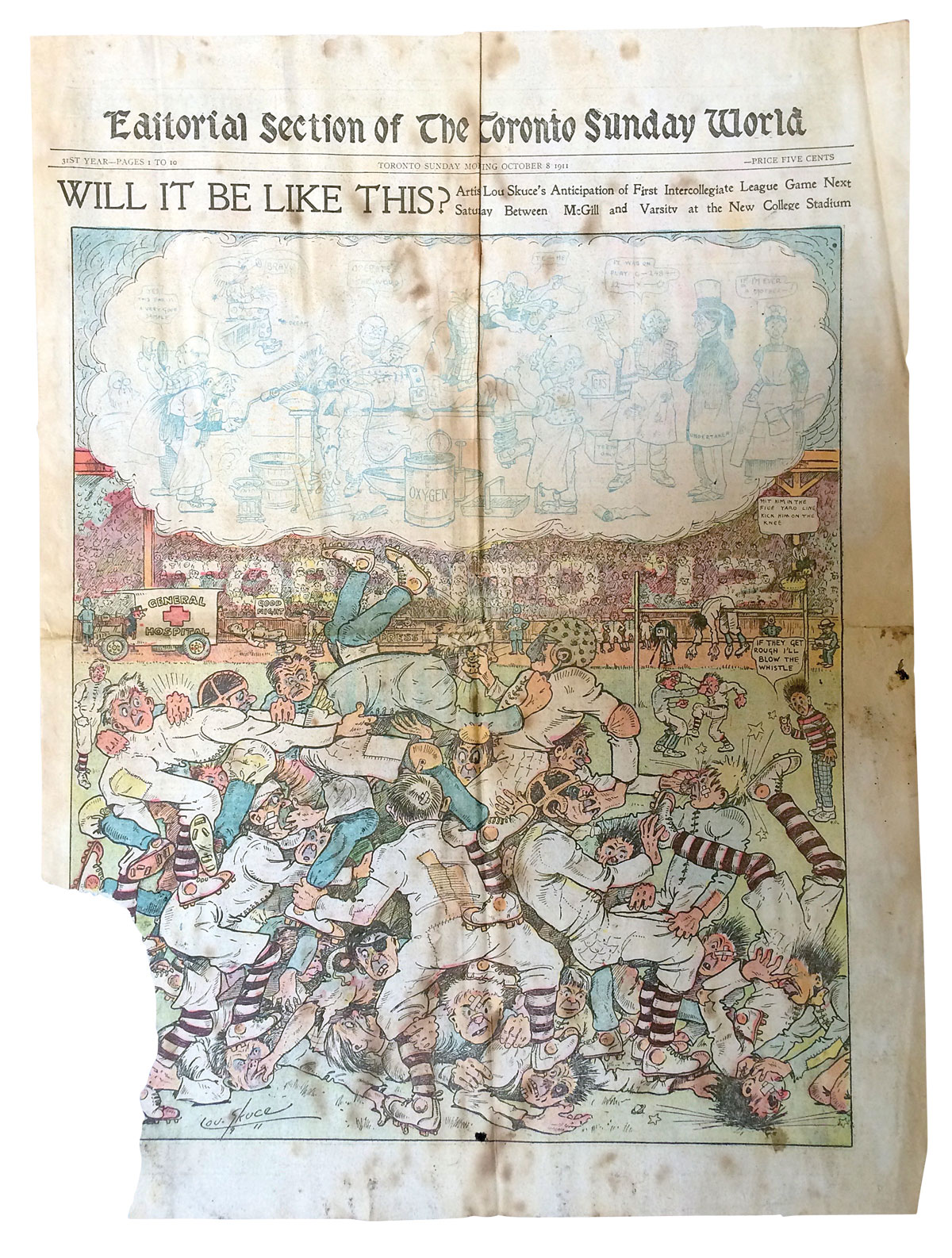

Skuce was the first to draw three-colour front-page illustrations for a Canadian newspaper. These covers frequently allowed him to showcase his fine-art skills and his ability to pack a wealth of information into a single drawing without losing sight of its focus: Santa Claus approaching the city by plane on Christmas Eve; a lively depiction of the first intercollegiate rugby game between McGill and the University of Toronto, at the then new Varsity Stadium; and a cutaway of the World’s own headquarters, titled “The Toronto Sunday World in the Making,” detailing the paper’s composition room, library, press, and art, editorial, and circulation departments, that foreshadowed his press club mural.

Skuce’s longest-lasting and most regular contribution to the paper was the character Mr. Fan, described in the World’s pages as “a middle-aged gentleman, who never becomes bored with life. Altho the father of a large and tiresome family . . . Mr. Fan always keeps up his spirits.” Mr. Fan began showing up early in Skuce’s tenure at the World, often, but not exclusively, in the sports pages to which he owed his name. His look changed radically between appearances, but his basic traits—a natty suit and an overly caricatured face topped with a tall bowler or occasionally a straw hat—remained consistent. In 1917, Mr. Fan began starring in his own strip, promoted by the paper as “the first full-page regular comic feature ever produced by a Canadian” and “the initial attempt of Mr. Skuce to put over a funny page. . . . There are very few people in Canada who are not acquainted with the work of this Canadian artist, the only Canadian cartoonist, by the way, whose work is funny.”

By 1913 Skuce’s celebrity was strong enough for the World to publish a thin digest of his drawings, titled Play Ball!: A Book of Baseball Cartoons. For ten cents, plus coupon, World readers received a twenty-four-page book capturing “a pictorial evolution in baseball, caricaturing the various phases of the game.” On-staff cartoonists specializing in sports to the extent Skuce did on the World were rarities in the Canadian newspaper industry, and his position as both caricaturist and commentator was a vital part of the paper’s voice. Skuce’s sports cartoons could be as much about the business of sport as sport itself, alternating from cheerleading to humorous criticism to compassion. A 1915 How It Looks To Us showed a hockey player eyeing an Armed Forces recruitment poster and commenting, “Gee, that would be a great way to keep in good condition.” In the same space the following week, what appeared to be the manager of a ball team sat on a chest of mothballed baseball equipment, above the caption “Twix’t love and duty,” bat in hand, the previous week’s cartoon at his feet, as Mr. Fan looked on in sympathy.

In 1914, Maclean’s, in a feature on Canadian cartoonists, declared Skuce a rising genius. Soon, he was contributing to newspapers and magazines across the country, including the Canadian and the Goblin. “Name it and Lou will draw it,” said a write-up in a 1921 catalogue published by the Newspaper Artists’ Association. “Versatility is his middle name. Pretty girls and manly games, hick politicians and snappy shows—these are the things which made his name on the Sunday World. His full-page features carry a knockout punch. He gets action into every line.” Maclean’s eventually hired Skuce on a regular basis, usually to illustrate the work of the Ottawa columnist J. K. Munro. A 1922 ad in the Globe touted, “C. W. Jefferys and Lou Skuce are only two of the famous Canadian, English and American illustrators whose best work appears regularly in maclean’s magazine,” which surely was news to the World.

The Star began competing with the Sunday World in 1910, when it launched the Toronto Star Weekly, a weekend read with many of the same sections and features as the World. By the nineteen-twenties, societal mores were loosening and popular amusements were no longer of interest only to the middle class. As a result, more newspapers began carrying moving picture coverage and colour comics. The daily edition of the World published its final issue on April 9, 1921, after being acquired by the Mail and Empire. The Sunday World continued for three more years before being absorbed into Star Weekly, in 1924—an irony considering the first edition of the Star had been printed on the World’s press.

Skuce once told a reporter that he planned to give up cartooning and begin making his living as a fine artist, but when he left the Sunday World, in 1923, a year before it folded, and moved to New York, it wasn’t to paint over-the-mantle landscapes for wealthy Upper East Siders. Skuce continued working in areas where he’d already had financial success. He took a twelve-month contract with J. R. Bray’s Bray Studios, one of the first studios devoted solely to animation. Bray was an early home to a number of successful illustrators and animators, including Carl Anderson, the creator of the comic strip Henry; Walter Lantz, who designed and wrote Woody Woodpecker; Paul Terry, whose Terrytoons studio produced Mighty Mouse and Heckle and Jeckle; and Max and Dave Fleischer, who created popular animated versions of Betty Boop, Popeye, and Superman. Skuce was a pioneer of animated film in Canada. He wrote, drew, and directed the short The Making of a Cartoon for Filmcraft, a Toronto-based studio that produced several shorts and a single feature, Satan’s Paradise, before the death of its founder, Blaine Irish, in 1923. At Bray, Skuce worked in the studio’s commercial division, which produced mostly educational filmstrips.

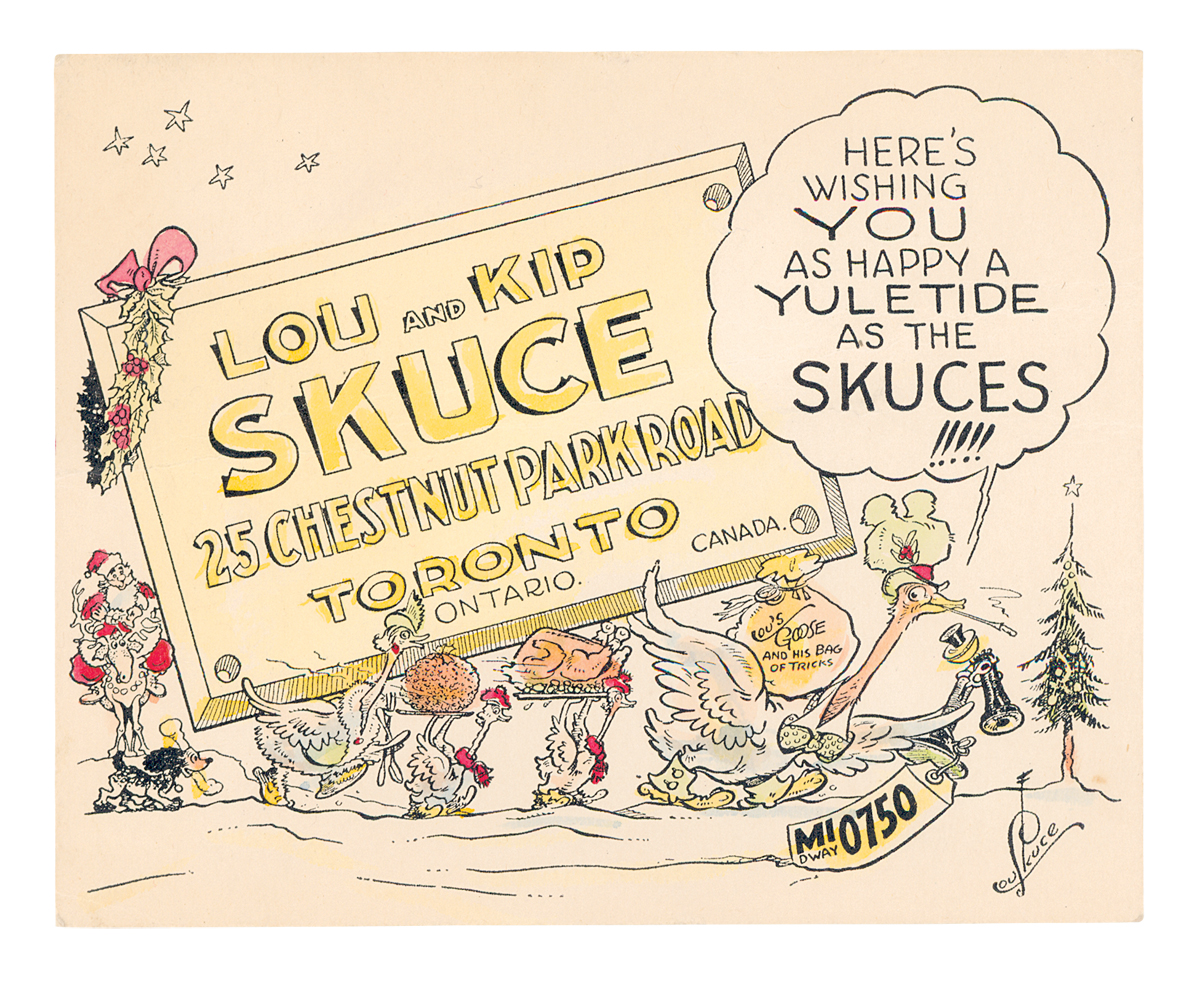

Early in his career, Skuce began using an unnamed small black owl as his “mark” on many illustrations. After leaving the World he created a new signature character: Lou’s Goose, a name Caricature magazine called “an unavoidable accident.” The wisecracking bird with a hat worn at a rakish angle appeared increasingly in Skuce’s work, and soon rivalled the popularity of his creator.

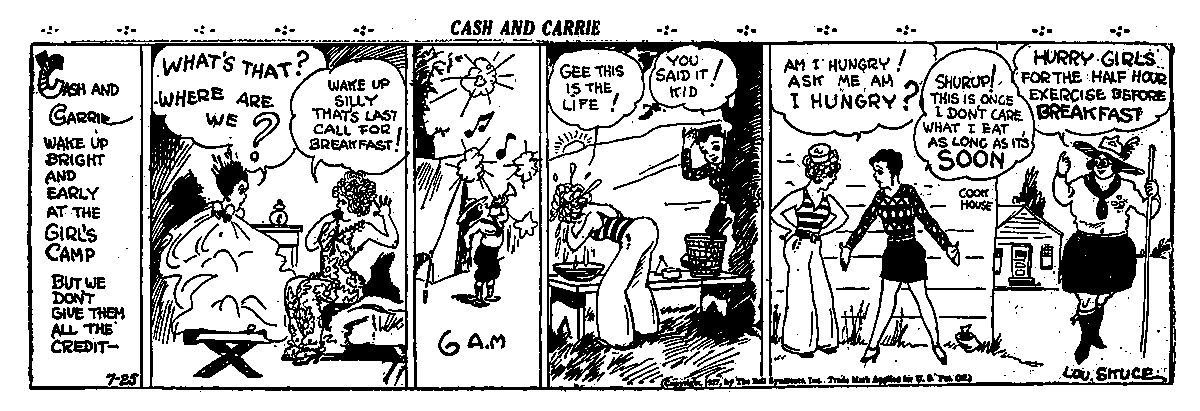

Skuce’s main focus in New York remained newspaper cartooning, in particular comic strips, an art form that had begun to take hold in North American papers in the late nineteenth century and increased in popularity after the New York Evening Journal introduced the first full daily comic page, in 1912. Skuce spent three years as a ghost artist for various syndicates while pitching strip ideas of his own. Merit Newspaper Service Corporation eventually agreed to distribute Cash and Carrie, Skuce’s story of two sisters who leave behind the fictional small town of Hickory Falls, Ohio (alternately referred to as “Littletown”), to seek fame and fortune in New York (“Bigtown”). Cash and Carrie, according to the preview strip that appeared in newspapers across North America, on January 10, 1927, were “happy, wholesome, modern girls; but they view Life and Men from different angles. Cash is more interested in real men and things domestic, while Carrie fancies frivolity and fun and her ‘Boyfriend’ must know all of the latest dance steps. . . . You’ll find them interesting.” Cash and Carrie began as a Sex and the City for the flapper age. The girls often found themselves in awkward dating situations, while trying to launch careers. Cash found work as a stenographer in the Wall Street brokerage office of Mr. Bott, while Carrie floundered in her attempts to become a Broadway dancer.

Two months after Cash and Carrie’s launch, Skuce was replaced, inexplicably, by a new artist, Earl Hurd, another animation pioneer. Together with Bray, Hurd developed many of the processes involved in celluloid animation that dominated the field for nearly a century. He worked at a number of studios throughout his career, including Terrytoons, his own Earl Hurd Productions, and Disney, where he helped adapt the Brothers Grimm’s tale of Snow White into the first full-length animated feature. He also created several newspaper strips, including Trials of Elder Mouse, the flapper comic Susie Sunshine, and Bobby Bumps. Post-Skuce, Cash and Carrie were sent on a visit home to Hickory Falls, where Hurd frequently abandoned them in favour of two new secondary characters: Lem Wheeler, a bicycle-riding telegram delivery man who wore square sunglasses and a moustache that covered the lower half of his face, and Ol’ Man Hoppit, an older gentleman with a long white beard, black overcoat, and oversized fedora, who had no trouble accompanying Lem on his “rush” deliveries, despite being hobbled by crutches due to what presumably was a permanent case of gout. Together, the duo zipped across town, often providing local gossip to a reporter for the Hickory Falls Bugle.

On Monday, April 4th, three weeks into Hurd’s tenure, Cash and Carrie opened with a caption informing readers, “The scene now changes to Cash’s office.” As suddenly as it began, the Hickory Falls storyline was dropped, along with all of Hurd’s characters. Skuce’s signature again marked the strip, and distribution was now credited to the Bell Syndicate. I asked Allan Holtz, a comic strip historian and author, to theorize on what might have happened. He told me the most likely scenario was Skuce “got disgruntled with Merit or otherwise started shopping around for a better deal. Bell Syndicate offered him a contract, so he stopped drawing Cash and Carrie. Merit didn’t want to lose the strip, so they got Earl Hurd to take over the drawing. My guess is Skuce and Bell both claimed they had a right to the strip, told Merit they had to cancel it, and after a few lawyer letters, Merit did just that, and Bell took over distribution with Skuce at the helm. The details are hazy, of course, but the basic plot is pretty clear.” This provides a possible explanation why redrawn versions of Skuce’s early Merit Cash and Carrie stories appeared in some papers in the fall of 1927. Bell “had no qualms about dated strips—they liked to sell a series from the start,” Holtz said.

By 1927, the changing role of women brought on by the suffrage movement was mirrored in a proliferation of working girl/flapper strips on the comics page. The most successful examples distinguished themselves beyond their obvious premise. The star of Martin Branner’s Winnie Winkle the Breadwinner worked to support her parents and brother. Chic Young’s pre-Blondie strip Dumb Dora featured a lead who was smarter than her name suggested. Skuce sent Cash and Carrie on vacation to a girls’ camp and featured a storyline about the invention of a square-doughnut machine. “Cross Word Puzzles are all of that,” one reader wrote, in verse, to the Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Telegraph, but “Cash and Carrie, a little flat.” The strip was carried by as many as a hundred and fifty newspapers at its peak, and was cancelled in less than eleven months.

Little Nell was the lone serious continuity strip created by Gene Carr, a newspaper cartoonist who entered the field at fifteen and pioneered the use of sequential panels. His Lady Bountiful is considered the first comic with a female lead. Little Nell was another Jazz Age story of a small-town girl trying to make it in the big city, launched in December, 1927, by United Features Syndicate. Initially, it looked like the strip might share Winnie Winkle’s edge, teasing the possibility that Nell’s idea of success wasn’t high kicking but studying to become a psychoanalyst. Soon, however, it was obvious that Nell saw her future on Broadway, despite never going on an audition. Little Nell was wordy and disjointed, and was discontinued after only four months. Instead of ending cold, the final strip showed Nell, having returned home in failure, on the telephone with a friend, Mary Ann Gay, herself headed for New York. “You must see me before you go to the city . . . There’s no work and the men, oh Mary Ann I must tell you about the men!” Nell warns. “But I have a job to go to in the city—on a news paper with Lou Skuce the cartoonist,” Mary Ann replies in the final panel, above the note: “Watch for Mary Ann’s adventures beginning in Monday’s paper.” Given Little Nell’s lack of popularity with readers, this spinoff ploy seemed designed to promote Skuce, still a bankable name despite Cash and Carrie’s failure. On April 16, 1928, five months after the cancelation of Cash and Carrie, Skuce launched his second strip, Mary Ann Gay. Mary Ann Gay’s premise was nearly identical to Cash and Carrie’s. “Follow her little trials and tribulations and loves—you’ll find them interesting,” promised the debut installment. Cash and Carrie’s dynamic was re-established immediately, as Mary Ann took an apartment with an old school friend, the overweight Eva Little, and found employment as a secretary in the office of a Mr. Baggs. By the time Skuce had Mary Ann and Eva vacationing at a girls’ camp, he was lifting not only characters and jokes from his previous strips, but whole panels—composition, dialogue and all. Mary Ann Gay’s run was shorter even than Cash and Carrie’s, ending abruptly on October 6th, with Mary Ann and her new husband, Bud, honeymooning in Niagara Falls. When Bud fails to catch Mary Ann’s hat after it’s caught by the wind, she begins to sob: “Don’t speak to me! And don’t ever again say you love me!”

“The proverbial struggle to gain recognition became the lot of Lou Skuce, just as it has been with many others,” Ben Batsford, a Canadian cartoonist with the King Features Syndicate, wrote years later about Skuce’s New York period. “Toronto said ‘How Are You’; New York said ‘Who Are You.’”

The earliest recorded Skuce—or “Skeuve”—ancestors were Scandinavian drainage engineers who left Norway for Holland to build dikes and drain the Dutch lowlands. Some relocated to England, in 1422, when John of Lancaster, the son of King Henry IV, hired them to drain his estate, north of London. In 1649, a naval officer named Skuce fought in Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army during the English conquest of Ireland. Skuces also fought alongside the Dutch-born William of Orange’s Protestant forces in 1690, at the Battle of Boyne, helping to defeat the Catholic army of James II as he tried to regain the British crown. During the Irish Rebellion of 1798, British Fleet Admiral Edward Skuce was stationed at Bantry House, in West Cork county. After the war, he settled nearby, in the small seaside town of Glengarriff, where he built a spacious slate home, which he named Derrynafulla. He married Elizabeth Coll, a widowed nurse, and together they had three sons, Thomas, James, and Daniel.

Thomas, born in 1804, met his future wife, Elizabeth Gosnell, a teacher and the daughter of a noblewoman, while working in Dublin. The couple, depending on which account of the Skuce family history you believe, immigrated to Canada, in 1849, either to seek a more hospitable climate for the sickly Elizabeth; to escape Elizabeth’s parents, who did not approve of Thomas; or to settle a farm on a plot Thomas was awarded under a potato famine land-grant program. Thomas and Elizabeth settled first near Ormond, Ontario, and later outside of Hallsville, in the area known today as North Dundas. They had eleven children, and when Elizabeth died, in 1869, Thomas promptly married Cynthia Eberts, a significantly younger woman who had been hired to look after the Skuce brood, with whom he had eleven more, the last when Thomas was eighty-eight years old.

James Skuce, Thomas’s third child and oldest son, was born in 1851, near South Mountain. Initially, James worked the family farm, but left at a young age to take up the blacksmith trade, eventually opening a shop in Ottawa with his brother William. He married Margaret Boulger, also the daughter of an Irish immigrant father, and together they had four children: John Howard, James Milton, Thomas Lewis, and George Orval. In 1890, James moved his family to Bell’s Corners, a lively village with two churches, a school, three hotels, a tollgate, a grocery store, and a blacksmith shop. Around 1903 James uprooted his family again when he moved them to Britannia Heights, a neighbourhood in what is now Ottawa’s west end. Britannia became a popular spot in 1900, when the Ottawa Electric Railway Company built an amusement park on the beach to entice city folk to ride its new Britannia Bay trolley line. For just pennies, Ottawa residents could travel to a puritanical version of New York’s Coney Island to swim, boat, picnic, and attend concerts. The Skuce home was situated on a plot of land uphill from the Ottawa River, at the corner of Richmond Road and Carling Avenue. The house was a traditional two-storey frame structure, surrounded by an iron fence, with large maple trees in the front yard, lilac bushes to the side, and a garden and small cottage in the rear. A walkway led from the dirt road of Richmond to the front entrance. The interior consisted of a parlor-style living room, a formal dining room, and a large kitchen housing a wood fireplace that carried heat to the three upstairs bedrooms.

James was a kind and patient man. He had a strong, lean build, and neither drank nor smoked. With his family, he regularly attended service at St. Stephen’s Anglican Church, and when it closed in the winter months James drove them all by buggy to the nearby Christ Church. James raised fruit, vegetables, hens, and pigs in his tidy yard. In Britannia, he found work at the Olde Forge, a single-storey log cabin built around 1830, by George Winthrop, that still stands today. Eventually, James built his own blacksmith concern onto the side of his home. He shod horses for eighteen cents, and removed the shoes again for twelve and a half. He also made winter slops for animals and built carriages. Margaret was James’s equal in every way: kind, affectionate, and active in the community. She was able to make ends meets to feed her family in tough times, and in better days indulged her artistic streak, painting landscapes in the garden and tending to her flowerbed.

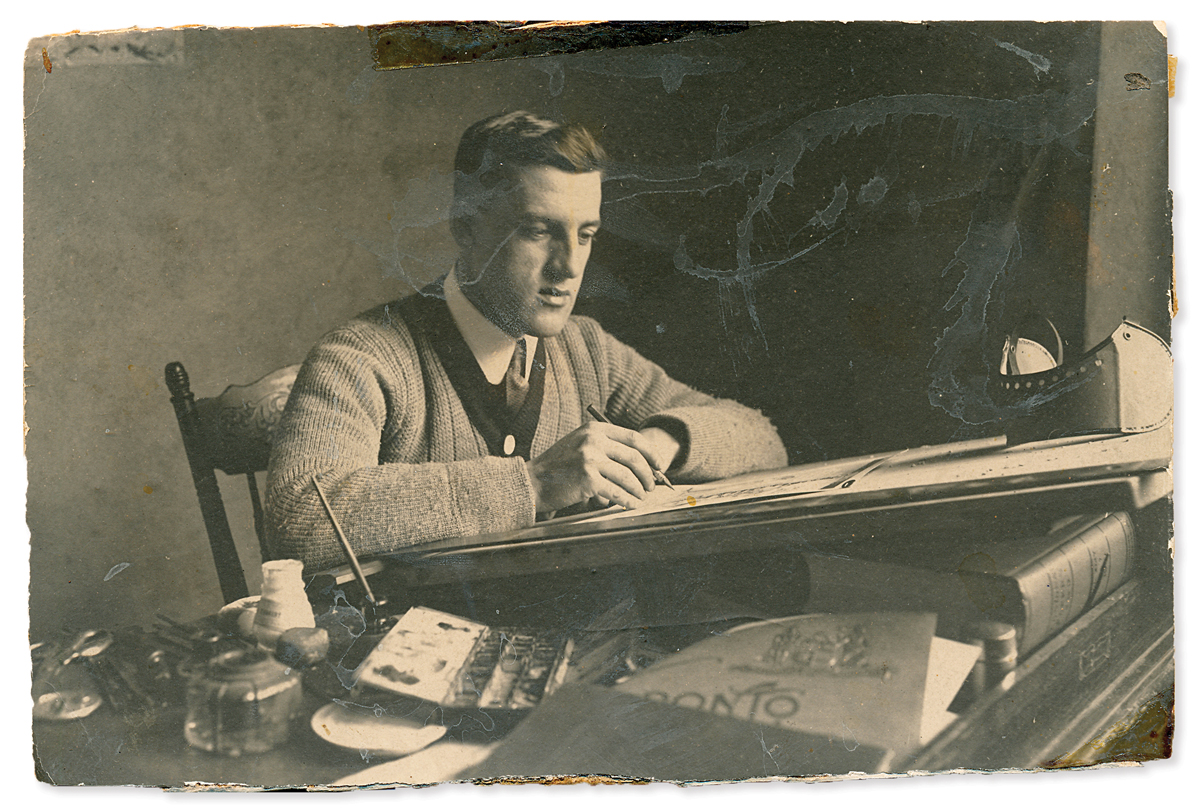

James and Margaret’s third son, Thomas Lewis Skuce, known simply as “Lou,” was born on July 6, 1886, in Ottawa. He attended Lisgar High School and by the age of eighteen was working with his father in the blacksmith trade. Lou’s youthful interests spanned athletics and the arts. He played drum in the bugle band of the 43rd Battalion, also known as the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa, a Canadian Expeditionary Force infantry regiment. In 1907, he became the head usher at Bennett’s, an ornate theatre located on Ottawa’s Sparks Street, and the first proper theatre in the city to show moving pictures. Bennett’s often featured vaudeville performances followed by a series of short films, billed as “the Bennettograph.”

The Skuce brothers were active members of the Britannia Boat House Club—known today as the Britannia Yacht Club—located just a short hike down the hill from their home. The club was formed, in 1887, by cottagers who spent their summers at Britannia-on-the-Bay, and soon became popular among canoe and rowboat enthusiasts. In 1900, Britannia co-founded the Canadian Canoe Association and hosted that group’s first annual regatta, on the Rideau Canal. Lou and his brothers paddled the war canoe, a fifteen-man boat usually raced to either a mile or half-mile. The event was especially popular, given the large size of its teams, and often drew sizable crowds. From the age of sixteen, Lou helped Britannia take as many as seven Canadian and one international war canoe championships. In 1901, he paddled to the rescue of a man and woman who had drifted toward a set of rapids after one of their own boat’s oarlocks broke. Lou transferred them into his canoe and spent half an hour fighting the current back to shore. His adeptness on the water made a news brief in the Journal a few years later especially amusing: “At a practice of the two Britannia war canoe crews the other night, there was a narrow escape from drowning when Lou Skuce fell overboard and was in danger but for his brother Milton. Milton did not know who it was till he got him near the dock. Lou says he can swim.”

As competitiveness between the groups grew, boating clubs began forming rugby, hockey, and lacrosse teams to keep their athletes active in the fall and winter months. Skuce played rugby with the original Ottawa Rough Riders and, later, the Parkdale Canoe Club, in Toronto, in the days before the formation of the Canadian Football League, and for at least one season, 1907–08, he played amateur hockey with a Winnipeg club, before dislocating a hip and returning to Ottawa.

Lou’s mother encouraged his interest in illustration and painting, and Lou exhibited work as early as 1904. One of his first jobs was as a show card writer for the Bryson, Graham department store, in Ottawa; passersby crowded the corner of O’Connor and Sparks for a glimpse of his hand-lettered advertisements. “It’s as natural for Lou to draw as it is for him to breathe,” Anson Gard wrote in his 1906 local history, The Humors of the Valley.

One to see his sketches would at once get the impression that he fairly bubbles over with humor, and yet he could no more tell a funny story than the Colonel could be serious at a funeral. No, Lou has to have a pencil in his hand before he can do any bubbling, and then he sees every point of humor in the subject, so much so, in fact, that one day needing an illustration rather than a cartoon, and he being the only artist who could do it at once, I was loath to let him try, but I did, and then I saw another side of the boy. He did the work so accurately that I could readily have believed that a staid old man with never a thought of any but the serious had done the picture, showing his double gift.

Around January, 1929, an advertisement for Buckingham cigarettes began appearing in Canadian newspapers. It featured a photograph of Skuce, dressed in his shirtsleeves and vest and sporting a trim flattop haircut, with a lit cigarette drawn into his right hand. Surrounding him were illustrations of Mr. Fan, Lou’s Goose, and four caricatures representing Politics, Sport, Fashion, and Drama. It read, “Lou Skuce, famous Canadian cartoonist, repatriated from New York by the Toronto ‘Mail & Empire,’ says: ‘Buckingham is sure throat-easy. It’s one of the good things Canadians miss when they cross the line.’” The ad was more than just another endorsement; it presented the Mail and Empire as a hero in the fight against brain drain and, more beneficially, helped Skuce save face on his return to Canada after failing—like his comic strip creations—to set Bigtown on fire.

Although Skuce had spent several years away, his syndicated work had given him an uninterrupted presence in Canadian dailies, and his stature at home was as strong, if not stronger, than when he left. As newspaper consolidation continued in the nineteen-thirties—notably the Globe’s purchase of the Mail and Empire—even the most popular cartoonists had to hustle for work between contracts and endorsements. The Toronto Daily Star captured Skuce’s modus operandi on October 31, 1936, beneath his drawing of an oversized hockey player standing astride a stadium filled with Lilliputian rugby players:

You look up from your mill and there’s Lou Skuce, who draws the pictures, and Lou says it’s a fine day, and how’s tricks, and wouldn’t it be an idea if he were to draw another picture for the paper.”

So you say a picture would be fine, but you just can’t tell him, “Go home and draw a picture”—it’s got to be about something.

Lou makes his eyes all squinty and studies far horizons intently. “Monday,” says Lou, “there’s to be a charity hockey game at the Gardens. The Leafs. Blues against Whites, or something.”

“The drawing is to be in black and white,” you remind him. “Color stuff—that’s The Star Weekly.”

“This,” says Lou, “is no time for wisecracks. I’m figuring out an idea. Now, hockey’s starting Monday. And rugby’s just in the middle of the season and very hot. Don’t you thing [sic] Rugby might be sort of sore at Hockey butting in that way?”

“Perhaps,” you say, without enthusiasm.

“Well, then,” says Lou, “we’ll have a drawing with two figures, one labelled Hockey all dressed up in skates and sweater and the other a rugby player and they could be—aw, shucks, that’s no good.”

“Look, Lou,” you say with your first glimmering of an idea in seven years, “have you ever read Gulliver’s Travels—?”

“Not another word,” shouts Lou, grabbing his hat. “I’ll be seeing you.” Like a shot he is gone.

To-day you find Lou’s brainchild on your desk in the cold, gray dawn and there doesn’t seem much to do with it but put it in the paper.

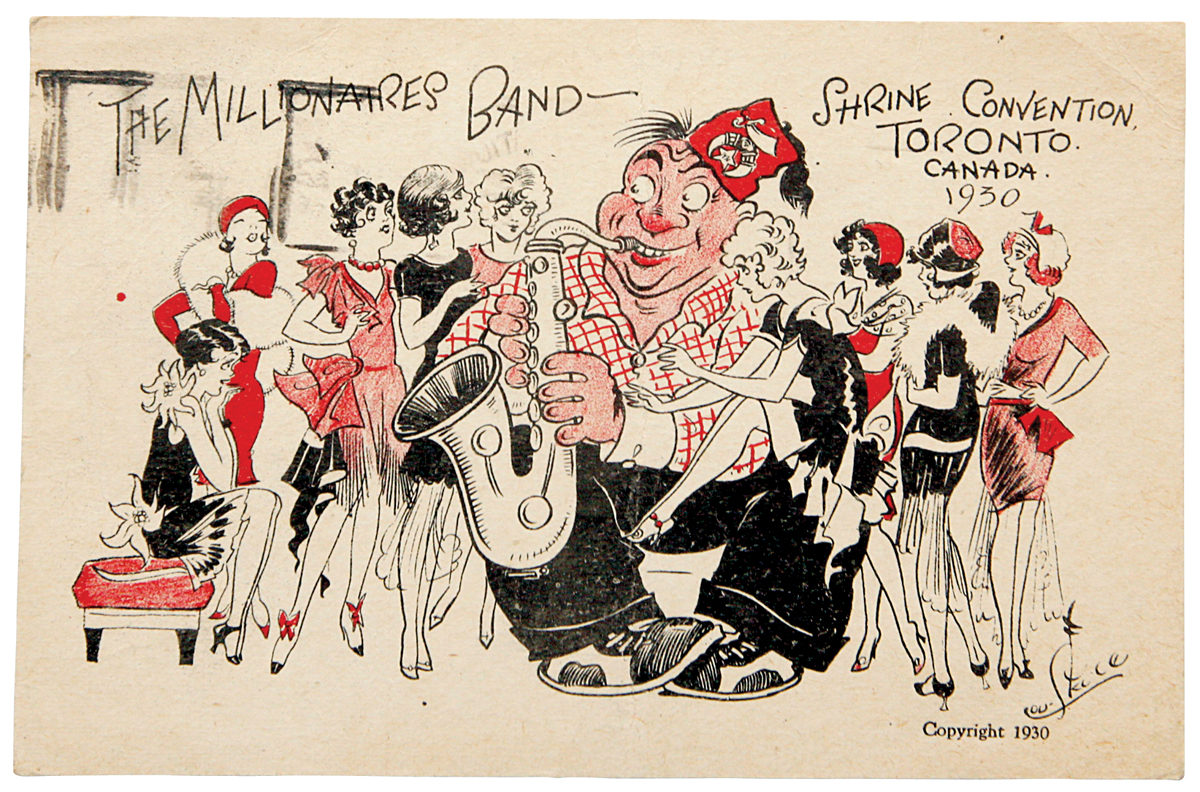

Skuce supplemented his newspaper income with advertising work as far back as 1924, when he drew a group of university students staring enviously at a dapper classmate outfitted in the latest fashion from Tip Top Tailors, and an art deco–style flapper posed beside a McLaughlin Buick, above the tag line “What more could a man ask for?” Shortly after returning to Toronto, Skuce opened Lou Skuce Studios, located on the penthouse floor, in Room 2202, of 80 King Street West, the Toronto Star’s legendary “Superman building.” The paper’s headquarters was so named for inspiring the look of the Daily Planet’s building in the comics created by the former Star newsboy Joe Shuster and his childhood friend Jerry Siegel. Promotional materials for the studio boasted a staff of “outstanding leaders in commercial art, magazine and newspaper illustration, cartoons and comics.” Beside its Toronto address, Lou Skuce Studios listed offices in Montreal’s equally impressive Southam Building, as well as rooms in New York, Chicago, and Hollywood. A 1931 ad in the Butte, Montana, Standard sought a “state manager with sales and organizing ability to operate on a royalty and bonus basis. State qualifications. No investment required but small working capital helpful. A proposition which will stand investigation. Address general manager. Western Division Lou Skuce Studios. Box 593, Arcade Station. Los Angeles, Cal.” More than likely—considering the studio’s biggest selling point would have been illustrations drawn by Skuce himself—at least some percentage of Skuce’s marketing was clever showmanship. The classified section of Popular Science magazine in August, 1953, listed Skuce’s Hollywood address, at 5873 Franklin Avenue, in an ad that read, “hollywood postmark! Letters remailed 25c ea.”

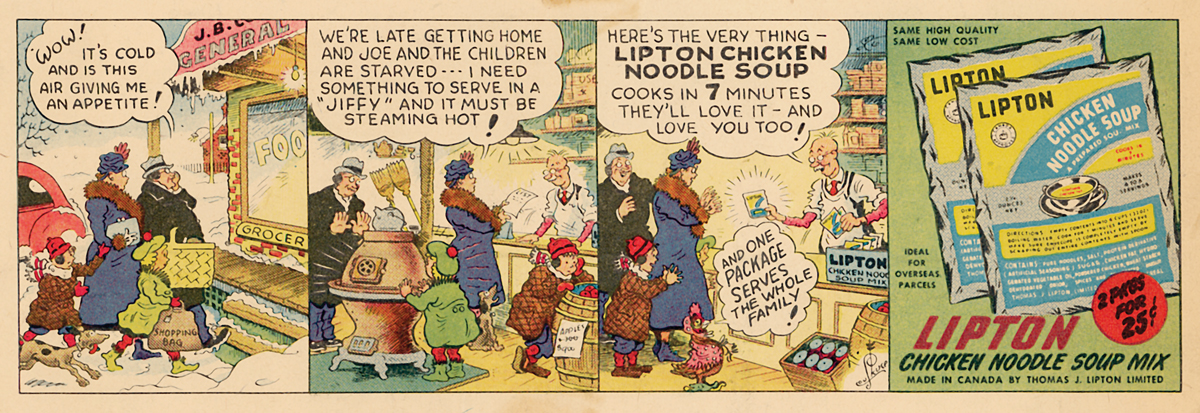

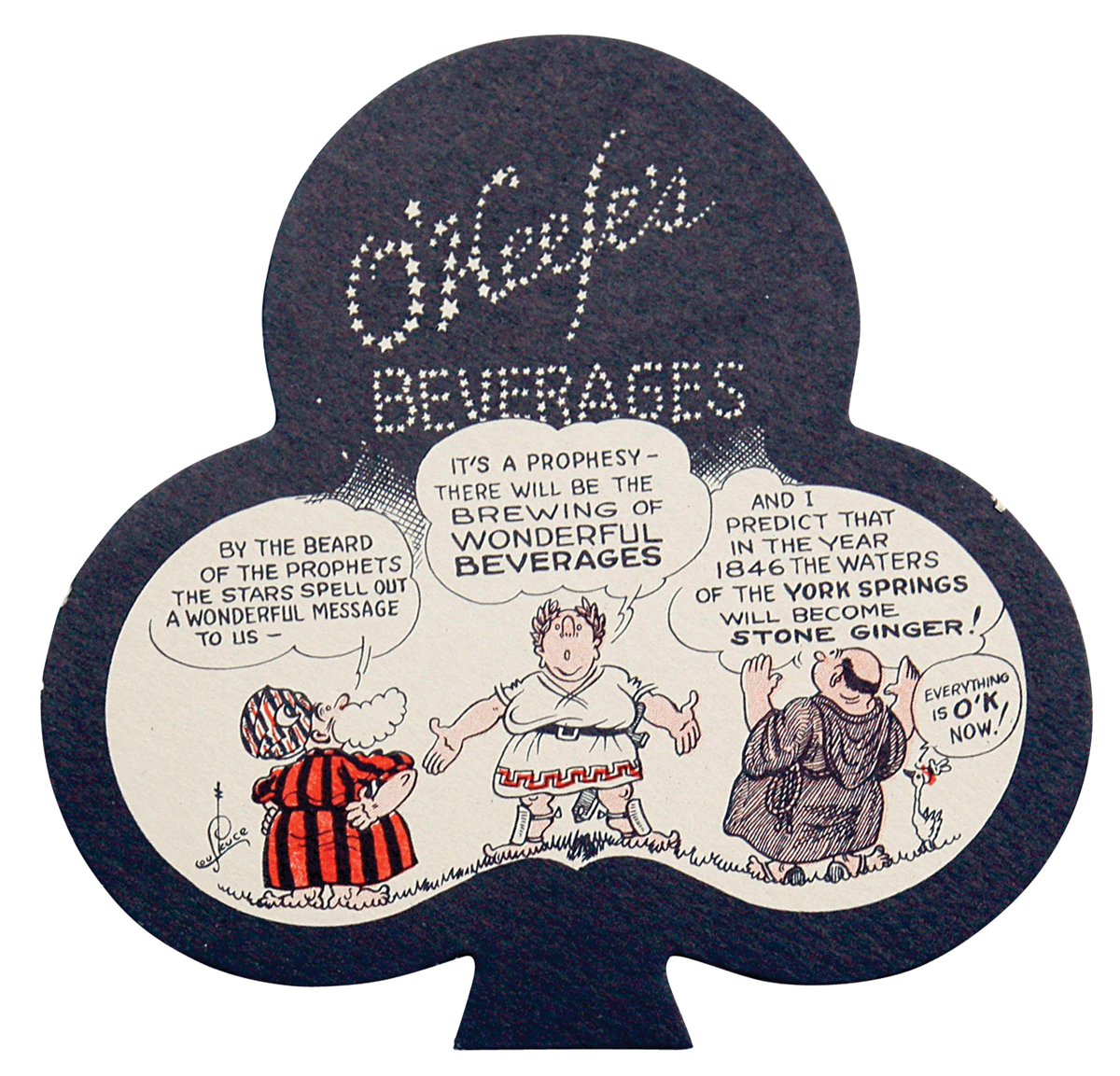

The studio’s major output, alongside print advertising, was illustrated promotional “blotting pads,” or coasters. A 1931 ad in the Montreal Gazette announcing the opening of his office there, said Skuce’s “output of cartoon blotters during the past five months is in the millions.” Skuce’s client list was exhaustive, and included Firestone, Hudson’s Bay, General Electric, Imperial Tobacco, O’Keefe’s Brewing, General Motors, Spalding, C.C.M., Lipton, Imperial Oil, and the Shriners, in addition to local coal dealers, dry cleaners, florists, taxi cab companies, dairies, and bakeries. Skuce’s advertising work rarely strayed from the lighthearted working-class humour he’d become known for, often sticking to a setup-and-punch-line format: “What this ol’ bus needs is more horse power!” the driver of a jalopy exclaimed on a coaster for Black Horse ale. “Yes—Black Horse,” replied his passenger, oblivious to the perils of drinking and driving.

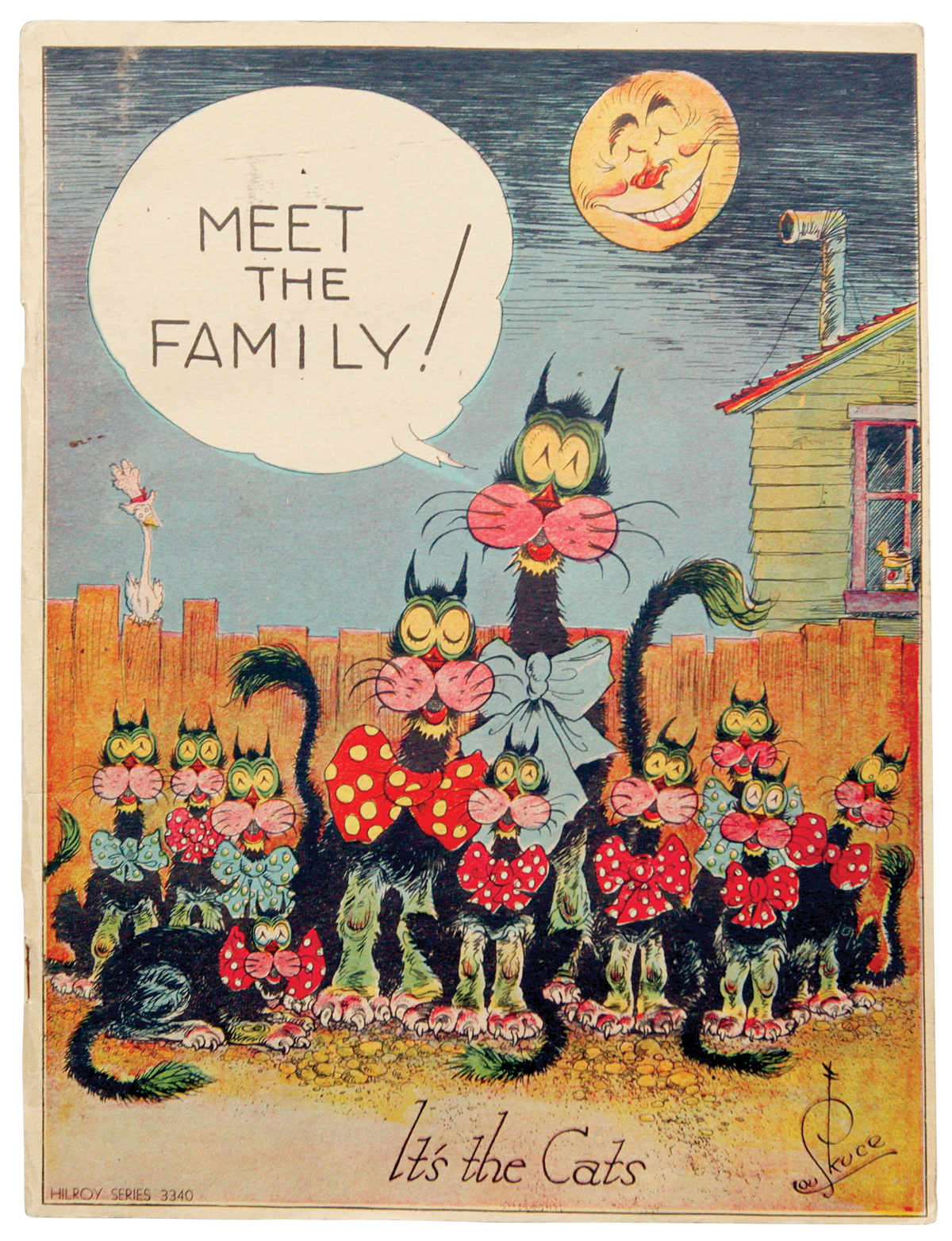

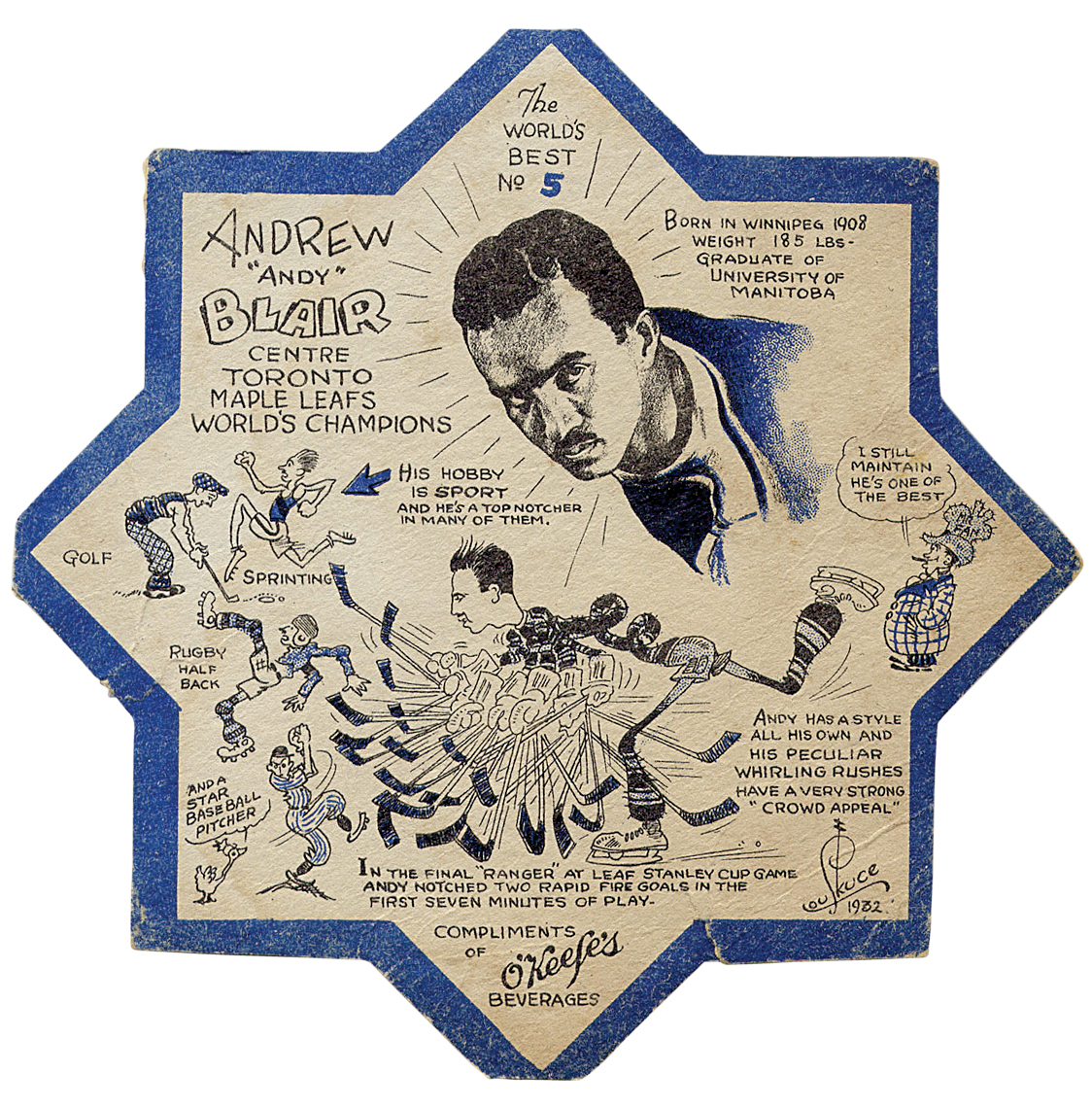

Skuce’s illustrations also appeared on a variety of merchandise. He drew scribbler covers for the Canada Pad and Paper Company, once offered free by Tamblyn drug store with each twenty-three-cent purchase of Minty’s toothpaste. In an escalating battle for toothpaste supremacy, patrons of Dr. Gardner’s toothpaste could obtain a Lou Skuce jigsaw puzzle of the Stanley Cup–winning 1932 Toronto Maple Leafs. A newspaper ad for the Hudson’s Bay Company in Winnipeg instructed boys and girls to “be on hand bright and early Saturday morning” for the 9 a.m. jigsaw puzzle special featuring “Lou Skuce Double Comics.” A pound of tea or coffee from Ottawa’s Red & White Stores guaranteed shoppers a “75 piece jig-saw puzzle free! A different puzzle . . . designed by Lou Skuce, the famous cartoonist, especially for Red & White Stores . . . more than 75 pieces and interlocking . . . no advertising on the picture, but lots of fun putting it together.” And O’Keefe’s once produced a confounding set of four blotters advertising stone ginger beer, which the company usually marketed to children. Each coaster was die-cut in the shape of a different playing card suit, and backed with bridge tips “for use at card parties or social occasions where beverages are served. The hostess will find these blotters a protection against the blemishes left by tumblers on bridge tables and other polished surfaces.”

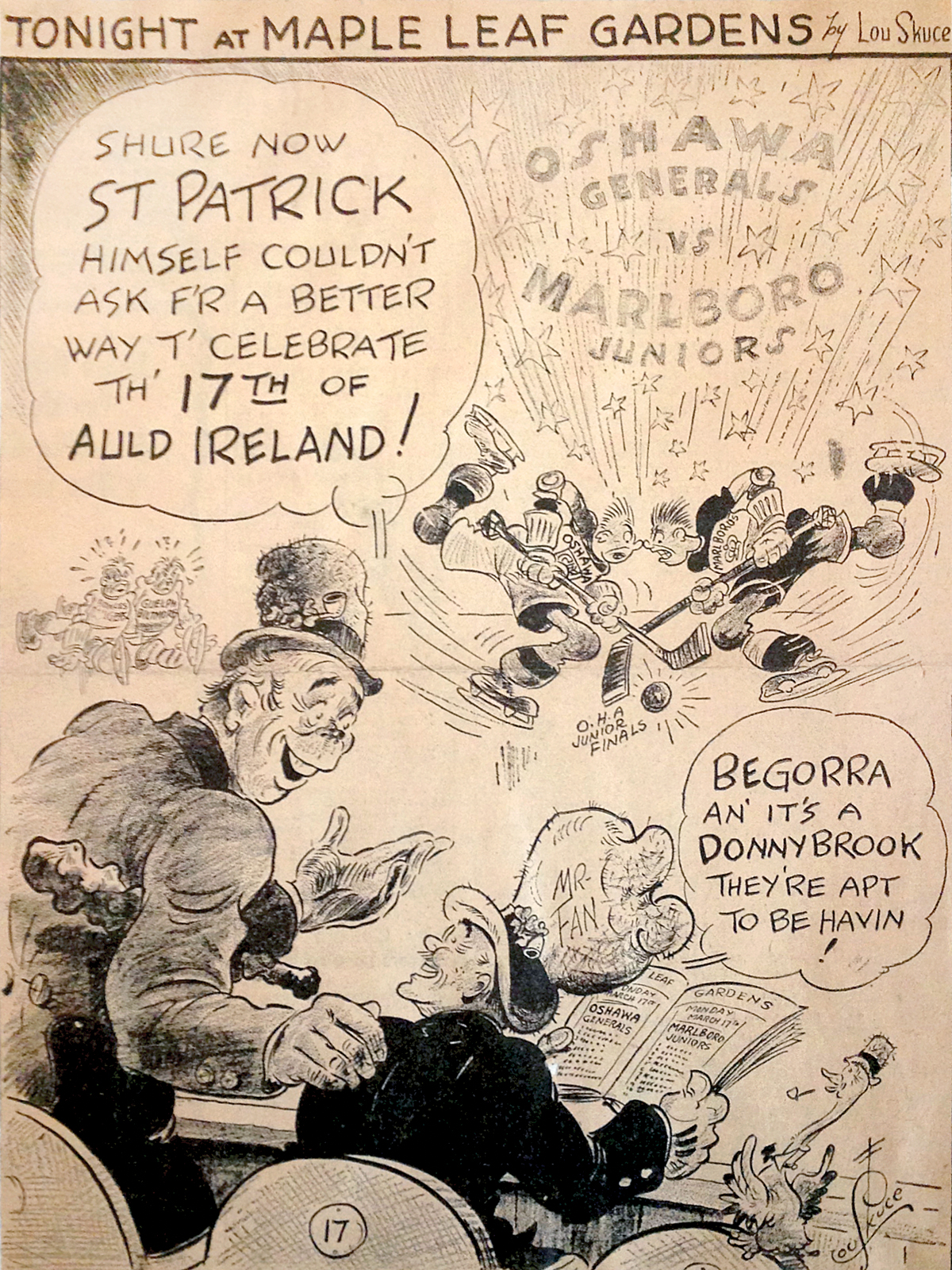

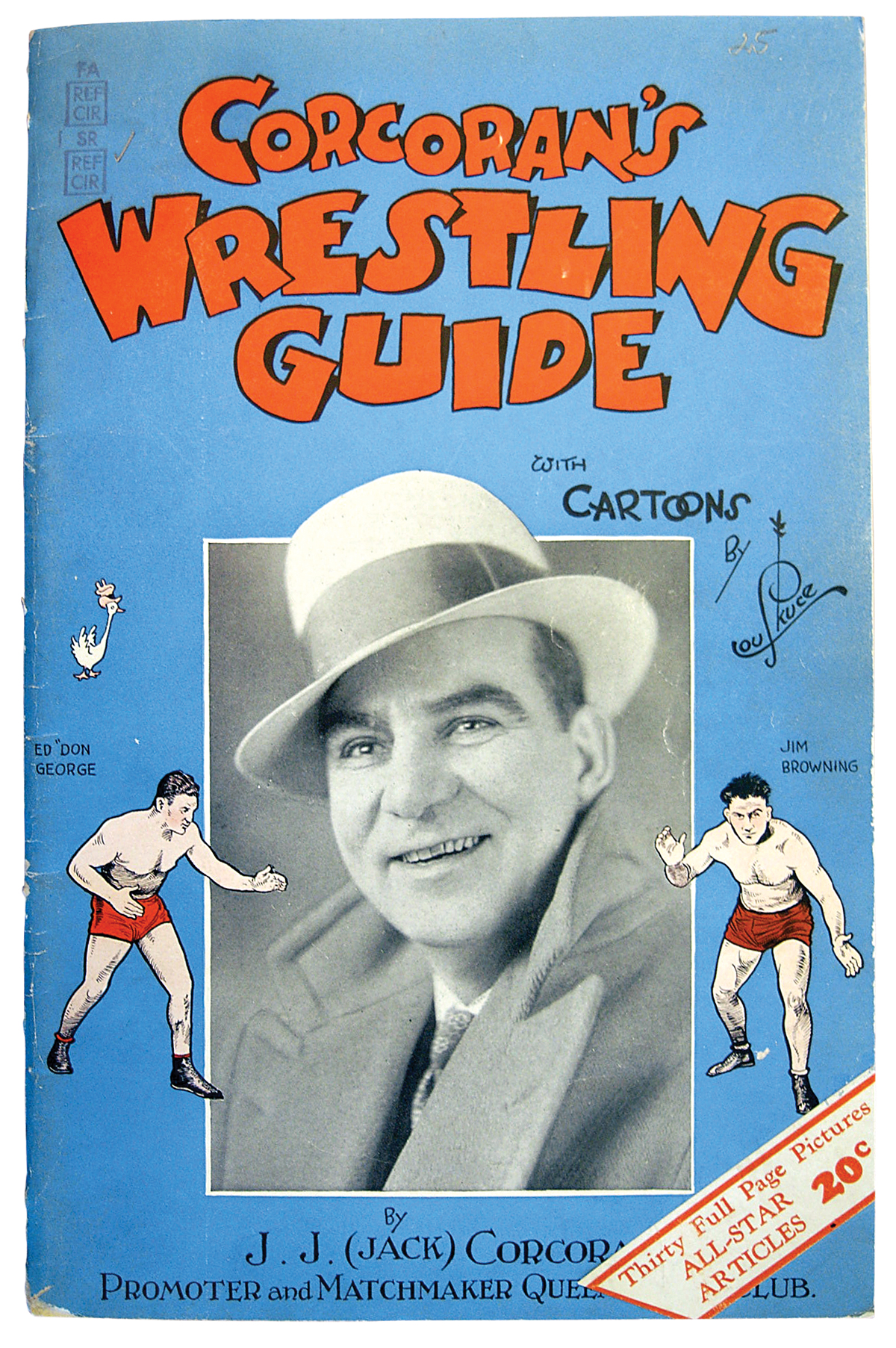

Sport remained a large part of Skuce’s life and career. He was a regular fixture at Saturday night Maple Leafs games, and encouraged the creation of the Lou Marsh Memorial Trophy, for outstanding athletes, named in honour of his friend, the one-time Toronto Star sports editor. Skuce’s own athletic background allowed him to draw especially detailed and accurate sports illustrations. His work in the area shows more consideration of composition than required by his lighter fare, and he was especially adept at balancing the friction between realism and cartoonishness in the single-panel profiles of sports figures that were popular at the time. Skuce once said his toughest assignment had been for Jack Corcoran, the wrestling promoter and owner of the Queensbury Athletic Club, in Toronto. Corcoran became infamous after he was accused of knowing match outcomes in advance. His reputation survived—he denied wrestling was anything but legitimate—and fans continued to turn a blind eye. Corcoran’s Wrestling Guide, published in 1935, was a sixty-four-page program featuring illustrated biographies of Corcoran’s talent. Skuce drew the wrestlers with a sensitivity and elegance that made each look like a champion—even cultural stereotypes like Matros Kirilenko, “the Terrible Cossack,” with his ushanka fur hat; and Jim Clinkstock, shown in full Cherokee headdress. Skuce’s book of baseball cartoons for the World demonstrated his early mastery of single-panel gags, but the Corcoran guide showcased in combination his fully matured talents as a fine illustrator, top-notch cartoonist, and talented letterer.

A profile of Skuce in a 1932 Maple Leaf Gardens program called him “a staunch friend of Maple Leaf Hockey Club since its inception.” Skuce’s portraits of Leafs players and staff hung on the Gardens walls for decades. He drew program covers and, on weeks when it looked like attendance to the Saturday night game might be low, he produced a comic advertisement for the local papers to boost interest. Skuce, according to the profile, had an “unselfish sympathy toward any athletic venture in the Queen City. No matter what time of the day you call on him, or how little time you give him on an assignment, he is always cheerful in acceptance, and prompt in execution.” Today, Skuce remains well-known particularly among collectors of hockey memorabilia. Sixteen Skuce-drawn coasters featuring the 1932 Maple Leafs, produced for O’Keefe’s Big 4 beverages—“A cartoon history of the world’s star hockey players on blotters”—often trade for hundreds of dollars each. The Vintage Hockey Collector price guide values a complete set at nineteen thousand dollars.

Skuce remained close to his family throughout his life. He visited Bell’s Corners frequently, and wrote lively letters to his mother in between. His brothers remained even closer: Jack and his wife lived in the backyard cottage while Orval raised his own family in the main home, taking over the property after the death of Thomas and Margaret, and staying in the house until the property was expropriated, to widen the intersection of Richmond and Carling, in 1959. A short residential roadway on the former site is named for the family today.

Skuce started a family of his own in 1913, when he married Dorothy Edis, of Toronto. They soon had two children: Pauline, who, as an adult, opened her own dance school and later in life spent time teaching crafts to seniors and the mentally disabled; and John, who worked as a hard-rock miner in Kirkland Lake, Ontario, and flew with the Royal Canadian Air Force during the Second World War. Dorothy died, of breast cancer, in 1928, at age thirty-four, around the time Skuce was returning from New York.

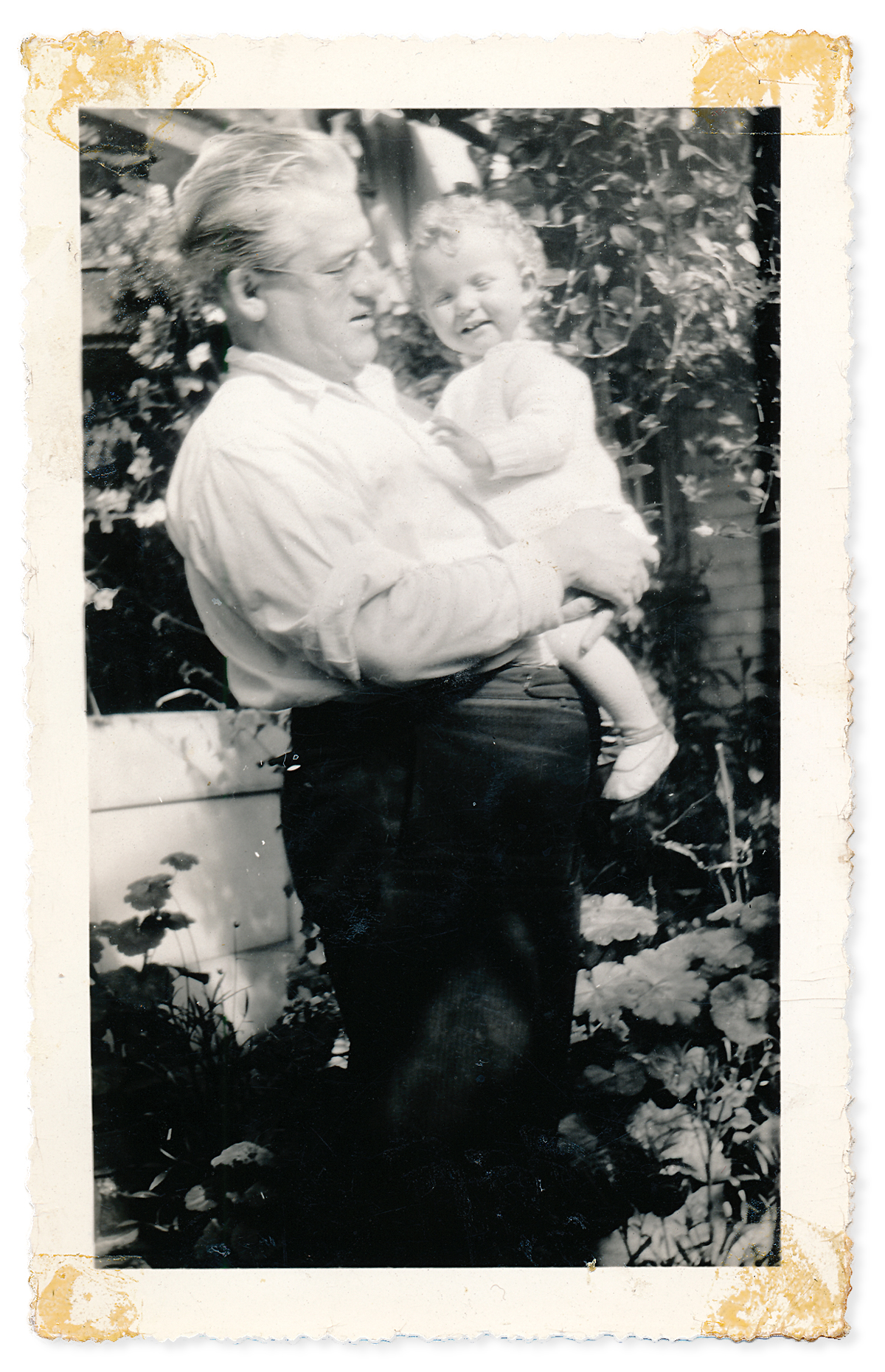

Skuce married his second wife, Ruth Kipling (Kip) Fraser, on October 15, 1932, at St. Stephen’s church, in Ottawa. Kip was the small and elegant daughter of William Alexander Fraser—the author who convinced Prime Minister Robert Borden to create the Silver Cross medal, presented to the next of kin of fallen soldiers—and the goddaughter and namesake of Rudyard Kipling, best known for the story collection The Jungle Book. Skuce and Kip also had two children: Nancy, in 1934, and Sandra, the following year. Nancy eventually married William Garden—whose father founded the original Garden Bros. Circus—and together they ran the Gene Cody and Kipling Bros. Circus for several seasons. Sandra inherited her father’s artistic side; she trained as a window dresser and floral designer, and later ran her own ceramics studio.

Kip, Nancy, and Sandra became a loving part of Skuce’s public persona. Each year, the Skuces sent Christmas cards featuring alternating caricatures of the family, one year depicted as flock of Lou’s Goose–styled geese, another as a company of radio players offering season’s greetings “over stations L-O-U and K-I-P a nation wide hook-up—sponsored by the skuce family.” Kip’s worldliness and family prominence combined with Skuce’s increased fame made them perfect fodder for a press increasingly interested in celebrity gossip. Nancy and Sandra appeared often in the society pages, while Skuce and Kip made national headlines on at least two occasions: in 1937, after Skuce lost control of their car on the highway, jumping a ditch and crashing into a pole; and again, in 1945, when Kip awoke to find Skuce overcome by coal gas fumes and called out to her sister, who was staying in the house, for help before collapsing herself.

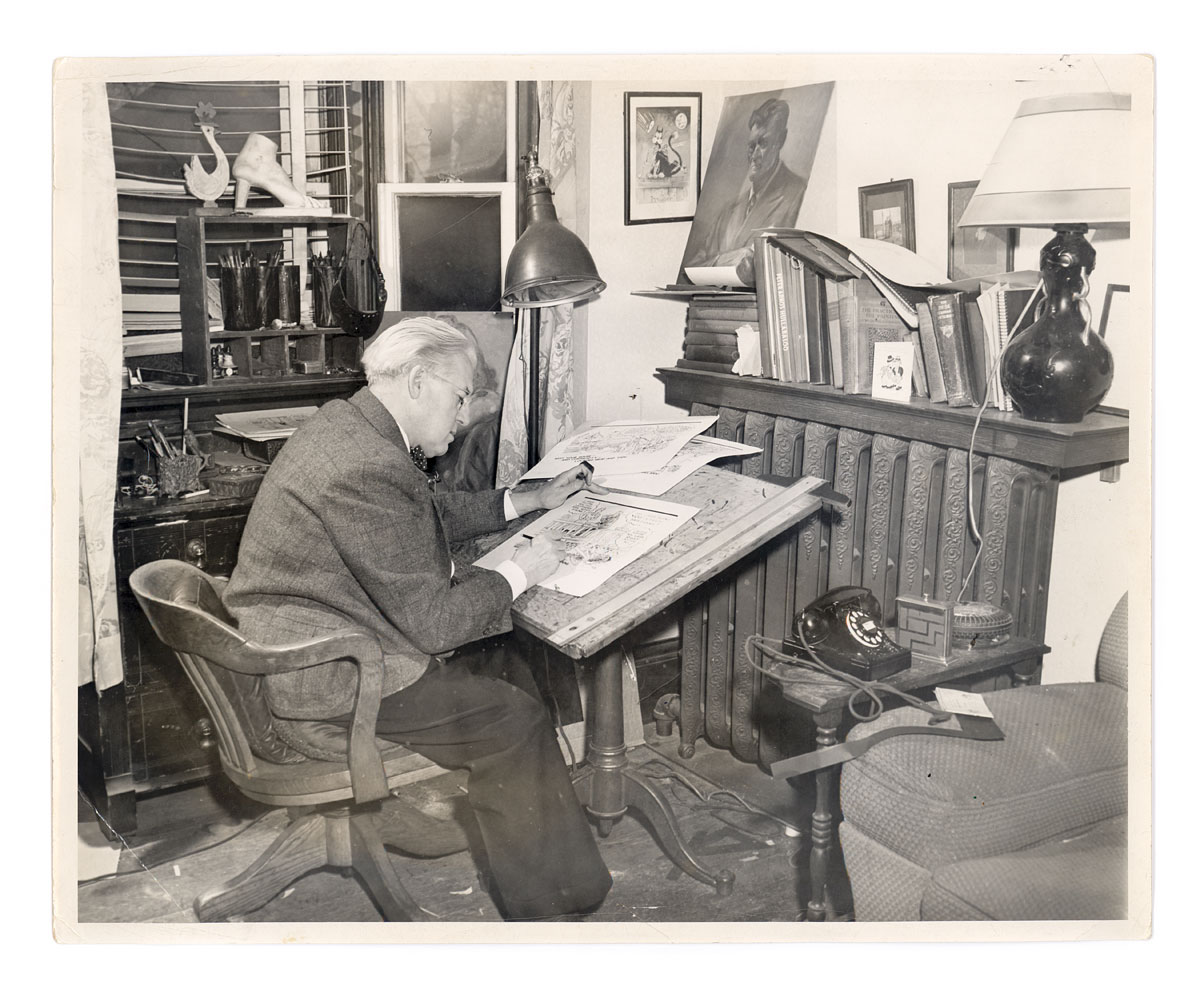

Skuce and Dorothy had lived a quiet and simple life, but Kip enjoyed a faster pace. Skuce happily obliged and, as a result, the couple often lived beyond their means. “Half of Lou’s problem was he wasn’t getting paid for doing things,” Evelyn Holstein, whose father was a close friend of Skuce’s, told me. “If he drew an ad for some resort up north, instead of getting paid, he got two weeks with family—that sort of thing.” There is no evidence Skuce and Kip ever owned a home. Instead, they moved frequently across the city, from Yonge and Eglinton to Deer Park to Summerhill. For three years the family lived at 35 Crescent Road, in the Boultbee House, designed by S. H. Townsend and built, in 1895, by Horatio Boultbee, the architect responsible for the colonial style of homes in Toronto’s tony Rosedale area. The home often was noted as the only in Canada with a real Italian sunken garden, a feature that pleased Skuce, an avid gardener who loved to grow flowers “in the summer for the winter, and grow them in the winter for the summer.” In the nineteen-forties, Skuce moved his studio into the family living room, “away from all the hustle, noise and smoke of a downtown area.” An existing photograph shows him seated in a wooden office chair, in front of a low drafting table. A makeshift shelf over the radiator holds a lamp, a variety of books, and one of Skuce’s own fine-art portraits. A wooden effigy of Lou’s Goose sits atop a desk, near the window, and a small end table displays a cigarette case and a Bell Model 302 rotary phone. Wessely Hicks, a reporter for the Telegram, once recalled visiting Skuce’ home studio while the artist was completing his mural for the Toronto Press Club. Skuce had “lined one wall of his large dining room with plywood in order to have adequate working space. . . . In putting up the plywood, Lou had sealed away most of the family silver. But no one suggested that he take the plywood down to rescue the silver, and I’m sure the thought never occurred to Lou. Lou was working and the family wasn’t going to disturb him. So they happily shared whatever silver there was around and put up with the muss and fuss, and ate in the kitchen.”

Skuce did not serve in the military during the First World War. Instead, he aided the war effort on the home front, producing propaganda for the psychological warfare branch of the defence department. He drew advertisements for Victory Bonds, and sheet music cover art for patriotic songs such as “Take Me Back To Dear Old Canada,” and “Home Again: That’s the Song of the World To Me.” Skuce played an even greater role during the Second World War, when he was known as the official cartoonist of the Allied nations. “If my posters will help the government just a wee bit along the road to victory,” he said, “my time is theirs.” A fierce version of Lou’s Goose sailed on the hull of the H.M.C.S. Middlesex, and, in 1944, Skuce’s mascot was inducted—presumably on an honourary basis—into the Royal Canadian Air Force. A line on the bird’s military I.D. noting visible marks on scars claimed “buck shots received in flights.” An animated theatrical short Skuce produced in 1947 opened with a man plummeting to the ground, a tattered umbrella in hand. He soon is saved by a parachute made from a Canada Savings Bond. As the man glides gently to earth, Lou’s Goose flies past, pausing to flash the message, “You’ll Never Be Sorry You Saved.”

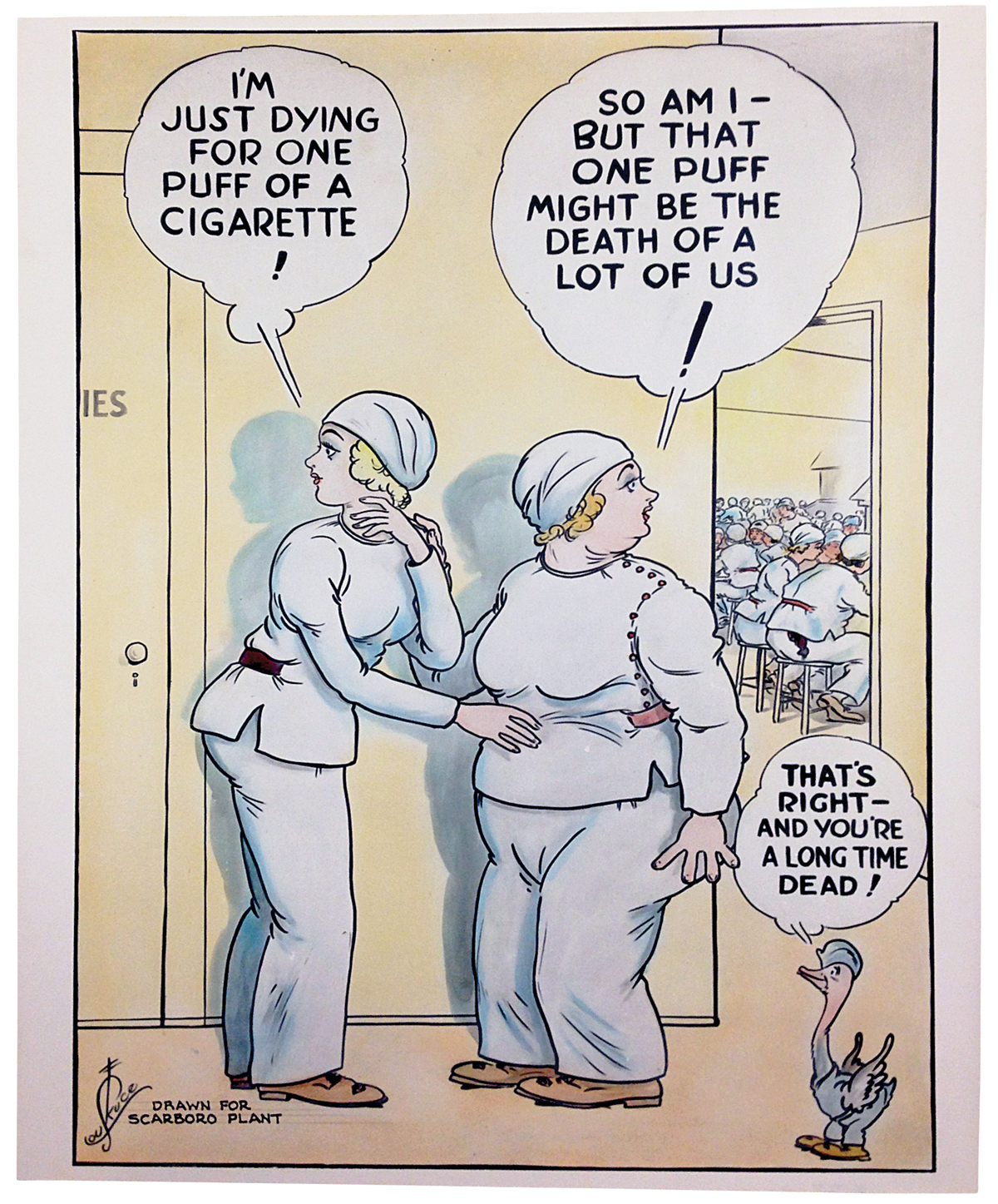

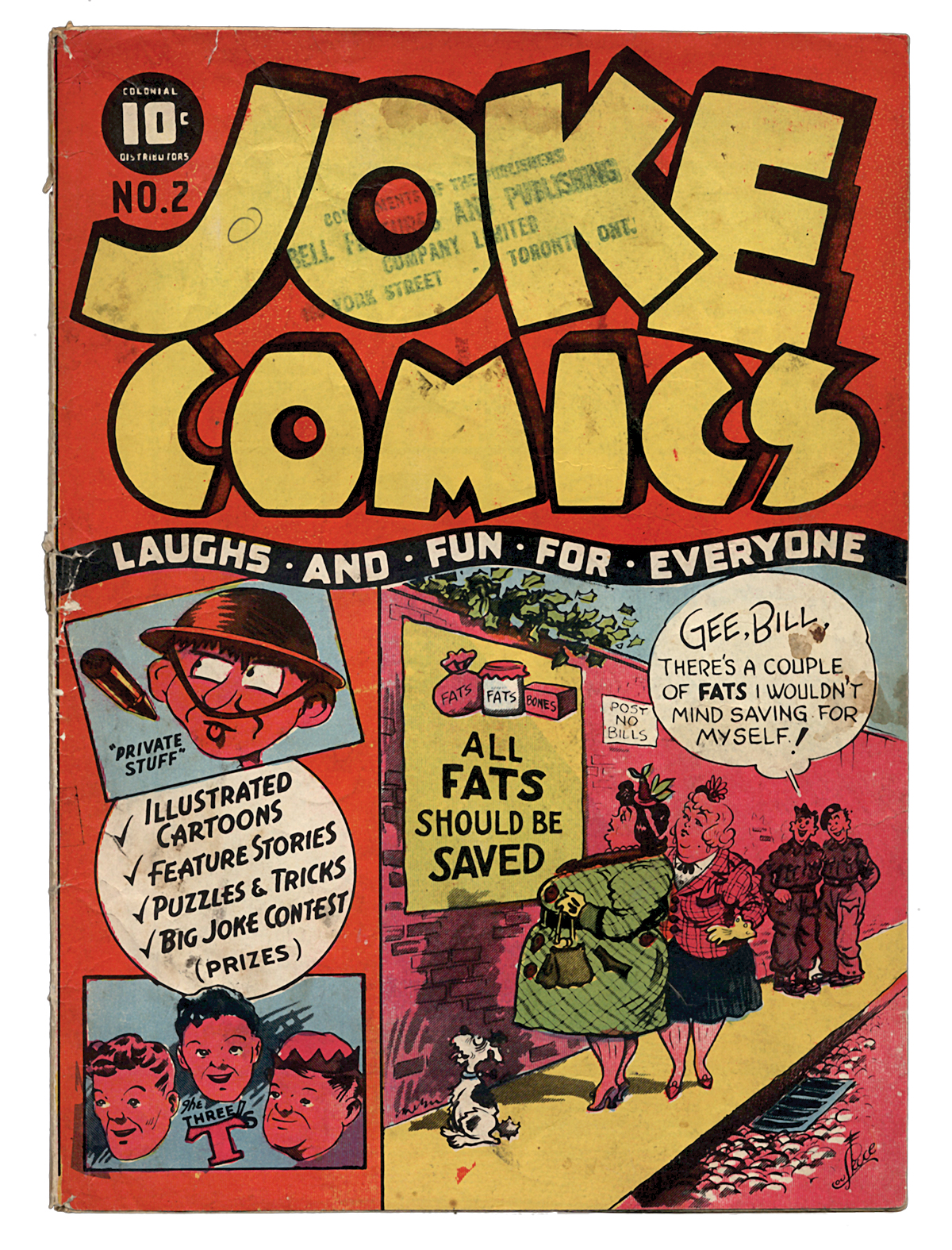

Skuce’s war work wasn’t limited to public propaganda. He was contracted by the General Engineering Company to create a series of safety posters for its Scarborough munitions plant, east of Toronto. These posters didn’t stray in style from Skuce’s advertising work, with set-up (“I’m just dying for one puff of a cigarette!”), punch line (“So am I—but that one puff might be the death of a lot of us!”), and the occasional sidebar from Lou’s Goose to drive the point home (“That’s right—and you’re a long time dead!”). Skuce also contributed to the “Canadian whites” comic books produced by Bell Features, a Toronto-based commercial sign business that shifted into the publishing field when wartime trade restrictions prevented the import of U.S. comics. Bell—no relation to the newspaper syndicate—produced the homegrown heroes Nelvana of the Northern Lights and Johnny Canuck. Artists such as Adrian Dingle and Fred Kelly made their names writing characters like Nelvana and Mr. Monster for Bell; Skuce, who by this time was a comic veteran, limited his contributions to cover drawings and single-page illustrations or gag strips, some of which were recycled from past projects, such as Corcoran’s Wrestling Guide.

Skuce’s biggest contribution to the war efforts took place on the stage. He had retained an interest in theatre since working as an usher for Bennett’s, in Ottawa, and was a lifelong member of the American Guild of Variety Artists, serving for many years as the chairman of its Toronto chapter. Skuce alternately is credited as a writer, producer, star, and set designer of several sketches that toured vaudeville circuits throughout Canada, the United States, and England around the time of the First World War. His name most often is associated with Billet 13 and The Shrapnel Dodgers, which both received attention in the press for being among the first war sketches produced in the United States. The Shrapnel Dodgers was a twenty-two minute performance staged by four soldiers, all of whom had been critically injured in France, and, according to a 1917 Variety review, “sought to give a semblance to the audience of how amusement in the trenches is or was secured.” When a later mention in Variety suggested the performers were not actual soldiers, Sgt. Major J. Parker, one of the show’s stars, wrote in response that “each man in the act has his Canadian Discharge Certificate, which reads on the reverse side, under the caption, ‘Campaigns,’ Service in France, and each man has also his discharge button on which appear the words ‘Service at the Front.’ . . . Although we fought with the Canadian Army, we are all Irishmen and I could tell you, if you want it, our opinion of the Old Countryman who hid behind the hospitality of the Stars and Stripes when his own country was in danger.”

Skuce was “a real sportsman,” Ted Reeve, the Telegram sports columnist, once said, “always ready to help some less able performer.” In 1919, Skuce frequently checked in on an artistically inclined soldier he had befriended at a military hospital. On one visit, Skuce was drawn to a powerful voice singing “My Wild Irish Rose” from another room. He looked in and introduced himself to Eddie Jackson, a soldier who had lost a leg at the Battle of Amiens, the year before. Jackson confided to Skuce that he was worried about his future prospects, having been too young to receive any type of career training before his injury. Skuce asked Jackson if he liked to sing. “Yes,” Jackson said. “It makes me forget myself.” Skuce encouraged the soldier to seek vocal training, after which Skuce found him work on Billet 13. Jackson said it thrilled him “to see the faces of an audience filled with interest and appreciation, and—oh, I suppose their applause means something, too.”

Early in his career, Skuce occasionally toured a stage show of his own. Sitting at a desk, in full view of the audience, he drew cartoons, cast onto a screen in real time through an epidiascope—an opaque projector that transmitted and enlarged images via a bright light and a series of lenses and mirrors. Epidiascopes descended from similar devices known as “magic lanterns”; both were common in the vaudeville era, though their popularity as a form of entertainment declined, along with vaudeville itself, with the rise of cinema. After returning from New York, Skuce began touring more frequently, billing the projector as his “Cartoonograph.” Claire Wallace, of the Toronto radio station CFRB, described Skuce’s show for her listeners in 1937:

Over a tiny, box-like machine Lou places a flat circle of ground glass. He gives the glass a quick coat of paint, then with a small stick begins to sketch out a design. It might be Lou’s famous goose, or it might be King George VI of England. But by mirrors the reflection of what Lou is drawing is thrown on a circular screen so the crowd can see. He works like lightning, scraping out a little paint there, a little here, doing most of his drawing upside down so the watching crowd doesn’t know until the last moment what his sketch will be. It’s an old-fashioned idea, Lou admits, but with a modern angle. And, is fascinating to watch.

After Canada joined the Allies against Germany, in 1939, Skuce tailored his Cartoonograph show as war-time entertainment, turning out “good likenesses of MacArthur, Churchill, Hitler, Hirohito and Roosevelt, with the full faces being superimposed upon some item they are identified with,” Billboard reported. “The Jap was drawn over the picture of a rat, while Churchill was sketched over a map of England.” Skuce continued to tour in peacetime, using his Cartoonograph show as another source of income. “I certainly don’t believe in specializing,” he told a reporter. “I find that by being able to handle all branches of art work I’m considerably better off financially than many others who have devoted all their time to one branch of work. I couldn’t be filling a vaudeville engagement at present if I had been content to specialize.” Often, Skuce presented his act as a mini-vaudeville review, employing his daughters Nancy and Sandy to perform a tap routine, dressed in green velvet costumes trimmed with gold sequins. He played a range of venues, including the Allentown, Pennsylvania, fair, the Toronto Beaches Lions Club, the Adelphie theatre, in London, and the grandstand of the Canadian National Exhibition. In 1942, Skuce signed a year-long contract to tour houses across the United States. His most notable booking was a three-week engagement at the Roxy, a six-thousand seat theatre just off of New York’s Times Square, known as the cathedral of the motion picture and immortalized by Cole Porter in his song “You’re the Top.” The Roxy was home to the Roxyettes dancers, who went on to become the legendary Rockettes when the theatre’s namesake operator left to open Radio City Music Hall, in 1932. Skuce shared an eclectic bill that included the dance team of Fred and Elaine Barry; the acrobatic Novack Sisters; and a screening of Iceland, a war film produced by Twentieth Century Fox.

“It was amazing,” Jack Holstein, who, as a young boy, saw Skuce perform at the C.N.E., in 1941, told me. “That’s the only thing I remember about the exhibition. That fascinated me. You could see what he was drawing but it would be entirely different when he turned it over. People would cheer, gasp, and clap. I’d never seen anything like it before or since.”

The Telegram reporter Wessely Hicks recalled Skuce’s liveliness as he watched him finish his mural for the Toronto Men’s Press Club, in 1951. “He lay on his back and worked and lay on his stomach and worked and he stood on step ladders and chairs and boxes and worked,” Hicks wrote. “And always he talked.” In a silent 1951 film reel, Skuce is shown completing and installing the mural. His hands move with a calm accuracy while still managing to seem casually slapdash. In a bit of staged comedy, two women, unconcerned with his presence, step over Skuce as he lies on the floor adding the finishing touches to the powder room door. Eventually, the film shifts to opening night. The artist chats with Viscount Alexander—whose Skuce-drawn portrait hung on the club’s wall—and mugs for the crowd, clapping his hands in glee after receiving a kiss on the forehead from Barbara Ann Scott. In 2009, four years before her death, I asked Scott what she remembered of Skuce from that night, nearly sixty years earlier. She said his mural “was very impressive,” and that Skuce was friendly, but “there were so many delightful gentlemen that were so good and so gracious that I think I was slightly overwhelmed.”

Nine months later, on November 20, 1951, Skuce died, of a heart condition, at the age of 65. He had performed at Toronto’s Sunnyside Pavilion as recently as late August, and a September 17th Globe and Mail report on a tribute dinner for Lillian Foster, the Telegram fashion reporter, noted that cartoons featured on the menu were contributed by Skuce “in spite of his serious illness.” Skuce filed a batch of cartoons to the Bell Syndicate shortly before his death, and died with a drawing board and unfinished comic at his side. He is buried in Beechwood Cemetery, in Ottawa, alongside his parents and his brothers John and James.

Little record remains of Skuce’s work today. None of his animation for Filmcraft or Bray seems to have survived, and the Toronto Sunday World, unlike its weekday counterpart, was never properly archived. Unlike his contemporary C. W. Jefferys, who built a name for himself as a master illustrator of Canadian history, Skuce did not become known beyond cartooning, and none of his characters, not even Mr. Fan or Lou’s Goose, remained in the public consciousness in the way James Simpkins’ Jasper the bear or Doug Wright’s Nipper continued to after their deaths. Skuce’s legacy is a product of the era in which it was made, when cartoons and illustrations were as ephemeral as the newsprint and blotters they were printed on. His singular talent aligned perfectly with the golden age of newspaper cartooning, and his success on the vaudeville stage managed even to outlast the art form itself. By the mid-fifties, millions of homes in North America would have a “magic lantern” in their living room. An unintentionally prophetic cartoon by Skuce, drawn in 1949, two years before his death, shows the artist seated at his Cartoonograph, as a dog by his feet exclaims, “It’s television!”