“He steps out. A gasp goes up. His suit’s starry. Spotlights bend off his blazer. He sings his song. The one on his suit. About being blue. The place goes ape. Folks hoot. Folks holler.”

The preceding could be a scene from the glory days of the Grand Ole Opry, just as easily as it could be text from a Derek McCormack–penned story. In fact, it’s both: a passage from McCormack’s recently released novel, The Haunted Hillbilly, a fictionalized account of the rise and fall of the country music star Hank Williams, as told by Nudie, his vampire manager-courtier. But replace a few words—“shirt” for “suit,” “reads” for “sings,” and “politely applaud” for “holler”—and the passage just as well describes the first of two October launches for The Haunted Hillbilly, held in the Brigantine Room at Toronto’s Harbourfront Centre. Often wary of the public spotlight (he once had a friend, the author Tony Burgess, read in his place at his own launch), on this night McCormack charmed the crowd of more than one hundred for nearly half an hour. Instead of giving an obligatory reading from his new work and saying good night, McCormack explained the origin of his attire that evening: a vintage black cowboy shirt with gold piping, smiley arrowhead front pockets, and a gold bar of musical notes across the front and back, purchased in Nashville by a friend who presented it to him earlier that day. From there, McCormack proceeded to give the audience a brief history lesson on the seedy underbelly of nineteen-fifties Nashville—the inspiration for his new book—before closing with a quick reading of The Haunted Hillbilly’s first two chapters. Hooting and polite applause followed.

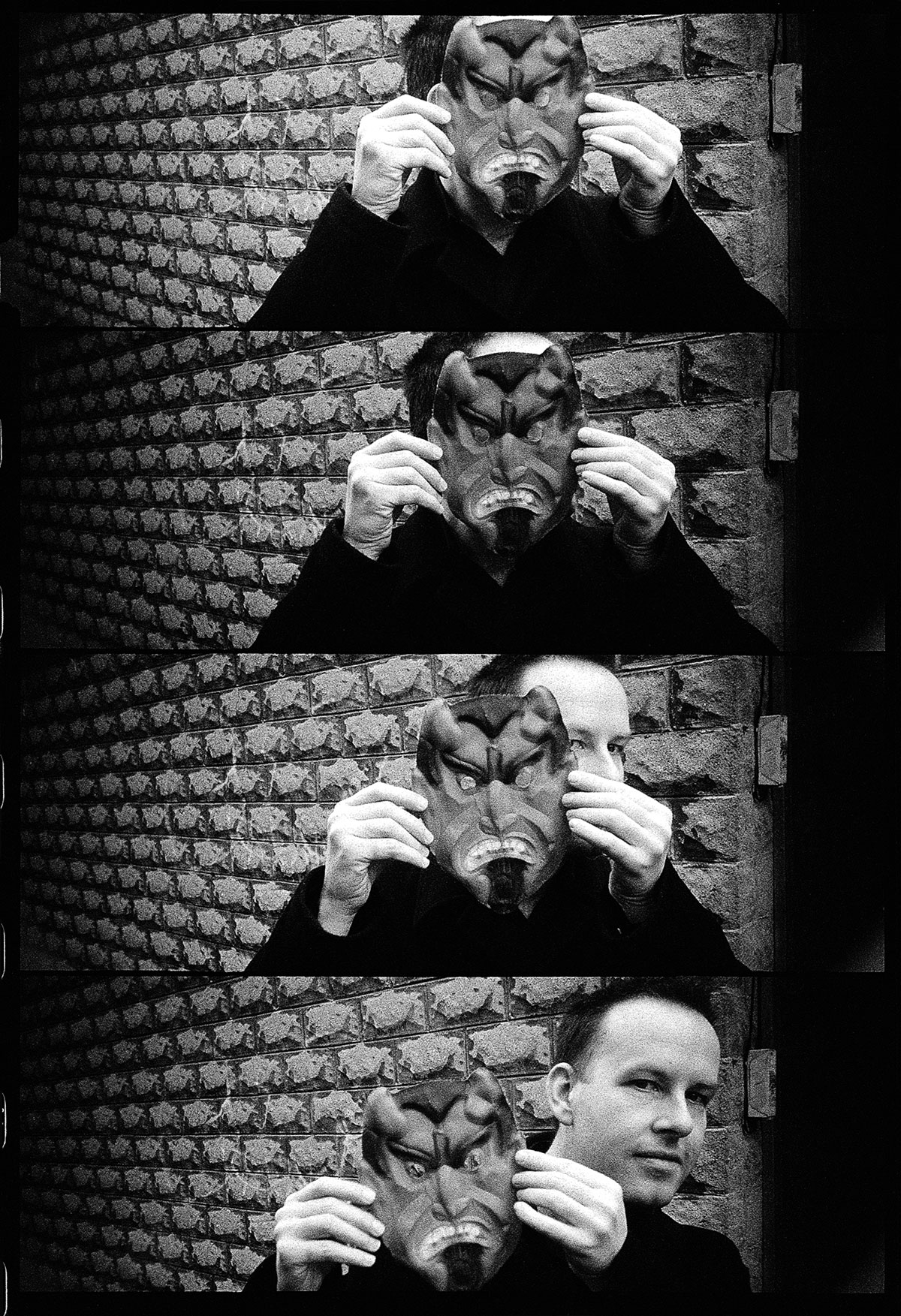

Painfully shy one minute and playfully catty and self-loathing the next, McCormack’s most endearing trait is his mock arrogance. “Make sure you say, as in all Vanity Fair profiles, that I speak in complete paragraphs,” McCormack instructed a few weeks earlier. It’s true: McCormack is well-spoken and interesting, especially when talking about the subjects that make him, and his writing, tick: country music, carnivals, county fairs, Christmas, and Halloween. It’s ironic that McCormack speaks in complete paragraphs. Anyone who has read his work will instantly recognize his quick, choppy prose—a style that takes Strunk and White’s style rule “Omit needless words” to heart. But despite his chattiness, a Vanity Fair–style day-in-the-life profile is out of the question. McCormack’s typical day consists of “a series of naps,” broken up by several hours of television, web surfing, eating, and writing. Readers of this interview will have to be content with McCormack’s back story.

McCormack, thirty-three, was born and raised in Peterborough, a quiet town in Southern Ontario and a gateway to cottage country. His father, Murray, a former real-estate salesman, and his mother, Cynthia, owned and operated a five-and-dime in nearby Lakefield. Housed in a century-old building complete with the original fixtures and shelving, the inventory of Ryan’s Five-and-Dime consisted in part of a large back stock of mid-twentieth-century pop-culture paraphernalia, from Davy Crockett hats to Cold War–era sci-fi ray guns. So plentiful were these former department-store staples that a young Derek and his sister, Melissa, along with a childhood friend, launched a satellite store in the family garage. (“We never opened to the public,” McCormack says, “because the neighbourhood kids would have torn us to shreds.”) As a teenager, McCormack worked summers in Ryan’s, first as a bagger, later as a stock boy, cashier, and display designer. During the holiday seasons, he accompanied his mother on trips to Wm. Prager, a Toronto-based manufacturer and distributor of store fixtures and display products, where they purchased giant Easter eggs, plastic ivy, enormous candy canes, and eight-feet-tall nutcrackers. “My mom would buy this stuff not only for the store,” says McCormack, “but that’s the stuff we’d decorate with at home, so we’d have, by far, the nicest house at holiday times.”

By his early teens, McCormack was openly gay to his sister and close circle of friends, and assumed gay by everyone else, including his teachers. Peterborough in the nineteen-eighties—“a time when everyone wore Iron Maiden T-shirts”—wasn’t exactly a shining example of homosexual acceptance. McCormack, who flaunted his sexuality defiantly with flamboyant clothing, jewellery, and hair dye, was openly mocked not only by other students, but also by his teachers, and threats of physical violence were a daily affair. “If someone said, ‘Hey, fag!’ in the hallway, I’d say, ‘Yeah, fuck you. Of course I’m a fag,’” McCormack says. “It’s weird now that I had the strength to go through it. I would never admit to anyone that it was a problem. I would never show any weakness at all….I don’t think it was bravery; it was just blind defiance. I just loathed them so much that I couldn’t back down at all, and I really felt being gay made me way better than those people.”

Considered an outcast by most of his peers, McCormack latched on to books at an early age and developed a heartfelt kinship—in the way only a lonely teenager can—with the outlaw tradition of such authors as Gebet, Baudelaire, Rimbaud, and Burroughs. “I really felt like I was one of them; I was a brother, I was in that circle, and it just seemed so infinitely superior,” McCormack says. “Then, when I was in high school, I got a subscription to the Face magazine and it was just a barrage of gay culture, so it just connected me to a world that was more cultured, cooler, smarter, sexier….That was a very gay moment in pop music, where you could have trashy pop like Dead or Alive or you could have Morrissey, but it was all there, and it was really, really flaming….I felt that was my heritage and it was way better than these scuzzball trash-can types. Of course I was completely deluded, but it got me through.” He pauses. “Did you notice that I’m speaking in complete paragraphs? ”

McCormack’s love of gay fiction, and his self-described verbal ability to charm or insult at will, convinced him he wanted to be a writer. Having read about and been fascinated by Tod Browning’s 1932 sideshow epic, Freaks, but without access to a repertory theatre, McCormack wrote his own version of how he thought the script should read. In the fifth grade, he wrote his own Hardy Boys book. For an English assignment in Grade 11, he wrote a story centred around an imaginary outcast from Andy Warhol’s Factory. “I was really pretentious,” McCormack says. “I was always bothering the teacher ’cause I’d put ‘fuck’ and lots of swear words and lots of gay stuff into my stories.” McCormack graduated high school in 1987 and left home to attend the University of Toronto, but dropped out after earning only six credits when he realized that spending four years obtaining a post-secondary education was “at odds” with his romantic sense of what a writer should be. He moved to Spain to write his first novel, a retelling of Petronius’s Satyricon. “It was terrible,” McCormack recalls. “I realized I was going to have to buckle down and really learn how to do it right.”

Although McCormack’s unpublished Satyricon novel was written in his now-familiar sparse style, it lacked nearly everything else that has since come to embody his stories. When he returned to Toronto after a year in Spain, McCormack wrote a short story about a young Peterborough-area teen afflicted with lupus, titled “Antibody: An Autobiography,” which was accepted and published by Grain magazine in 1992. Over the next several years, McCormack honed his writing in a series of stories, all set in Peterborough in 1952 and all starring characters named Derek McCormack—“an ephemeral being obsessed with ephemera”—who were not necessarily the same character from story to story. This time around, McCormack was reaching into his own life for subject matter. By 1995, his stories had appeared in nearly a dozen literary journals, and he had struck a deal with Gutter Press, a small Toronto-based publisher, which released his collected works under the title Dark Rides the following year.

The fictional Derek McCormacks of nineteen-fifties Peterborough bear more than a passing resemblance to the real-life teen Derek McCormack of nineteen-eighties Peterborough, with comic effect. The Derek McCormacks of Dark Rides are often shown as arrogant rubes—know-it-alls who are ostracized and beat up by their peers. “That’s me,” McCormack says. “They’re totally annoying, totally pretentious, and by the end of the story, something has broken them. It’s bravado like I had in high school. I would walk down the hall of Adam Scott Collegiate Vocational Institute thinking I was David Bowie, circa Thin White Duke….Every story in Dark Rides was based on some emotion or situation I’d been in, with the exception of any time Derek has sex, because I didn’t have any sex in high school.” Setting Dark Rides in the nineteen-fifties “was kind of accidental,” McCormack says. In a precursor to The Haunted Hillbilly, one Dark Rides story, “Men with Broken Hearts,” tells the tale of a young boy frantically attempting to make his way to a Hank Williams concert, only to arrive in time to see his hero being carried offstage, drunk, during his opening number. “Hank Williams played in Peterborough in 1951, and when I found that out I wanted to write a story about him playing there. Dark Rides came out of that feeling once I started to think about what it would be like to be young and gay in Peterborough in the nineteen-fifties, how claustrophobic and dark it would have been.”

McCormack followed up Dark Rides with two side projects released in quick succession: Halloween Suite (Pas de chance, 1998), a handmade collection of four interconnected stories about death, despair, and deception in nineteen-thirties Peterborough, and Wild Mouse (Pedlar, 1998), a collaboration of carnival-themed short stories and poems, written with the poet Chris Chambers. But it was his next major collection, Wish Book (Gutter, 1999), that brought McCormack back to the five-and-dime. While Wish Book contained the Halloween and carnival suites of his previous two publications, much of it centred around Turnbull’s, a nineteen-thirties department store, first introduced, albeit briefly, in Dark Rides, and based on the real-life Peterborough store famous for catching fire and collapsing in 1913, killing six. “The thirties are interesting for so many reasons. I guess that’s particularly from my grandparents’ stories of the Depression, how hard it was, the huge wildness of it, people being desperate. Peterborough had a huge hobo encampment, a lot of gypsies coming through, a lot of railroad bums coming through. It was like everywhere else in the Depression, but it’s all so romantic in my mind, it seemed like a perfect period to have a lot of oddballs show up, a lot of craziness, a lot of desperation—a good time for dime stores.”

Though all of McCormack’s stories take place decades before he was born, they are told with an authority that shows his love of his subject matter. He obviously draws heavily on the memory of working in his parents’ five-and-dime, but also manages to give perfectly detailed descriptions of candy wrappings, carnival games, and fake gorilla fur. “I do a lot of research for the stuff I’m interested in, and the rest I guess,” McCormack says. “That’s why I think the books take me so long to write. That’s why even though they’re short, I don’t really think they’re light reads….I think there are only so many times you can drop facts like that and not have people think you’re being ironic or coy or campy or something, so I have to really narrow it down to what’s important to me.”

As in Dark Rides, the characters in Wish Book (some of whom are again named Derek McCormack) are arrogant and self-important and usually meet their match by story’s end: a Boy Scout is duped by his fellow Scouts into believing he will never be a true tracker without seeing visions of an Indian master; a department-store employee is caught masturbating behind the two-way mirror in a changing room occupied by the crooner Bing Crosby; a naive reporter who fancies himself a newshawk is beaten by carnies who catch on to his attempt to expose the midway’s fixed games. “I think Wish Book has the most pompous people,” McCormack says. “People just caught in little worlds that they take to be very important, which is also a retail thing. It’s like having dominion over the hosiery department but still being unmanageably rude, being dictatorial. It’s like at Tiffany. Those guys are great. In the end, they don’t own Tiffany and they can’t afford anything they sell, but they carry themselves with that unbelievable wealth and privilege. I love that put-on.”

While not a complete departure from his previous books, The Haunted Hillbilly, released in September by ECW Press, shows signs of a shift in McCormack’s work. Despite it being his first book in four years (not including Western Suit, a sneak peek pamphlet of the book released in 2001 by Pas de chance), and impossible as it may seem, McCormack has learned to tell a longer story with even fewer words than before. The origins of The Haunted Hillbilly, McCormack’s first published novel, stem from a passage in Country, Nick Tosches’ revealing 1977 book about the country music industry’s dark side. Tosches reveals that the Country Music Foundation, located in Nashville, possesses two taped interviews with the legendary promoter Oscar Davis. Throughout his career, Davis had worked closely with such artists as Hank Williams, Ernest Tubb, Hank Snow, and Elvis Presley. In the interviews, conducted late in Davis’s life, in 1974, he revealed the many great, untold scandals of country music—a “who fucked who,” straight, gay, underage, and otherwise. The foundation has never allowed access to the Davis tapes. McCormack’s curiosity was too much for him to handle, and his mind began to wander. A long-time fan of Hank Williams and Nudie Cohn, the famous tailor to such stars as Williams, Presley, and Dolly Parton, McCormack mixed his love of country with his love of monsters, resulting in a phantasmagoric gay Nashville horror story, with Nudie as the vampire manager obsessed with Hank’s “museum-quality” ass. Nudie both makes and breaks the career and life of this very fictional Hank for little more than his own evil amusement. “I sort of got the idea to write a story where Hank had a gay manager….This manager had to have absolute power over Hank, it had to be a Col. Tom Parker thing….I read in a magazine published by one of Hank’s band members after his death—a little tribute magazine—that all Hank ever read were comic books. And then when Hank was in the hospital after back surgery, this band member would bring him monster comics, which were his favourites. So then I thought, ‘I’ll write it like a Tales From the Crypt,’ and that gave Nudie that absolute power. I know it’s kind of a lame metaphor, the manager as vampire, but it also let me completely bust out of the reality of it. I couldn’t find a way to write it where Hank would be so unquestioning. If I’d written about the real Hank Williams, it would be impossible because he was quite a feisty, clever character, so I just totally invented a story of him being a really passive good guy.”

If David Lynch’s Twin Peaks had been set forty years earlier and aired on HBO instead of ABC, it likely would have resembled a Derek McCormack story. For all their quirkiness and quaint pop-culture throwbacks, McCormack’s characters are often violent, if not physically or mentally, then in their intent: a novelty-store clerk drugs and then strips a young customer in order to shave his pubic hair, which he then uses for itching powder; a teen rapes a friend after accidentally knocking him out; a sideshow giant anally rapes a carny who has been selling plaster casts of the giant’s hand. As much as McCormack is lauded for his work, he also receives a fair share of criticism for the violence portrayed in his stories. But McCormack-style violence is more comical than anything else. “I think it’s funny. That scene with the giant is the first step toward what I think the new book is, which is completely Buffy the Vampire Slayer–style violence, where the violence is metaphorical,” McCormack says. “The violence is endlessly regenerative. In Dark Rides, Derek keeps coming back for more. I don’t think anyone really dies.”

McCormack’s work is equally analyzed for its treatment of gay characters. In his paper “Derek McCormack: In Context and Out,” published in the spring, 2001, issue of Essays on Canadian Writing, Peter Dickinson, a professor at the University of British Columbia, writes, the

commingling of the sexual, the scientific, and the scopic is heightened in Wish Book through the presence of fluoroscopes, X-rays, Spectro-Rays, and all manner of other arcane electromagnetic devices designed not just to see but also to see through bodies. Together with his penchant for cataloguing (ailments, behaviours, goods, practices, types), woven into the very narrative fabric of Wish Book, the presence of these mechanisms for reading the “diseased” body—and, by extension, one’s impure thoughts—suggests an almost Kinseyesque quality to much of McCormack’s writing.

McCormack admits to playing occasionally with the idea of the deviant gay body, but suggests this is one of many cases where his work is over-analyzed for a deeper meaning that isn’t always there. In this particular example, McCormack actually spent a great deal of time in the hospital as a child, and again in his late teens. “Hospitals are as fascinating to me as department stores or carnivals because what’s great to me is what’s behind the scenes—the lingo and the machinery and the pecking order of the people working there—so hospitals became another staging area.”

McCormack doesn’t always agree with critical analysis of his work, but says it’s important to him as a form of validation. He considers himself a member of the gay canon over the Canadian canon (his favourite authors being Dennis Cooper, Matthew Stadler, and James McCourt), but worries he’s not. “I’m trying to be part of a lineage, which I think I’ve mostly connected in my head. Those writers I love so much, straight people don’t even read. Straight people don’t even know about them, so that gets my back up and I feel, yeah, I am a gay writer because they’re enormously talented writers and poets that just beat the crap out of most of the stuff the New Yorker publishes, but no one reads them except gays who come across them in gay bookstores. So it makes me a little more defiant about it. I always make this argument, and people say, ‘What about Michael Cunningham and The Hours? ’ Not only was it the first best-selling gay book, it wasn’t even about gay men. It was about women. It was a multi-generational women’s novel!”

Though arrogant, Nudie, the narrator of The Haunted Hillbilly, is no rube. Unlike most of McCormack’s lead characters, his cleverness allows him to live to tell his tale. But Nudie’s day may yet come. McCormack has plans for two more books starring Nudie. The next will show him working his evil, ass-sucking magic on the country star Jimmie Rogers, while the third instalment will explore his early days in Paris, including his vampire origins. Readers may have to wait awhile for their next hit of Nudie, however. Recently, McCormack has turned his passions into a growing side career as a non-fiction writer. His 2000 story on Halloween for Saturday Night magazine earned him a National Magazine Award nomination, and he recently signed a deal with House of Anansi to write a history of Christmas in Canada titled Shopping Days, slated for release in 2005. Also in the works: another Pas de chance collaboration, this time on the history of fake snow, due in time for Christmas, 2004. McCormack will have to clear his plate of these projects before the release of The Haunted Hillbilly: Volume 2, but rest assured—Nudie will return…