In the early days of this century, I was invited to give a guest lecture at my alma mater, the University of Vermont, on the topic “preservation and the press.” Americans are, overall, better at preserving buildings than Canadians—more inclined to feel patriotic toward their architecture than to gut it. But, as a Canadian working in media, I thought I had something to bring to the table.

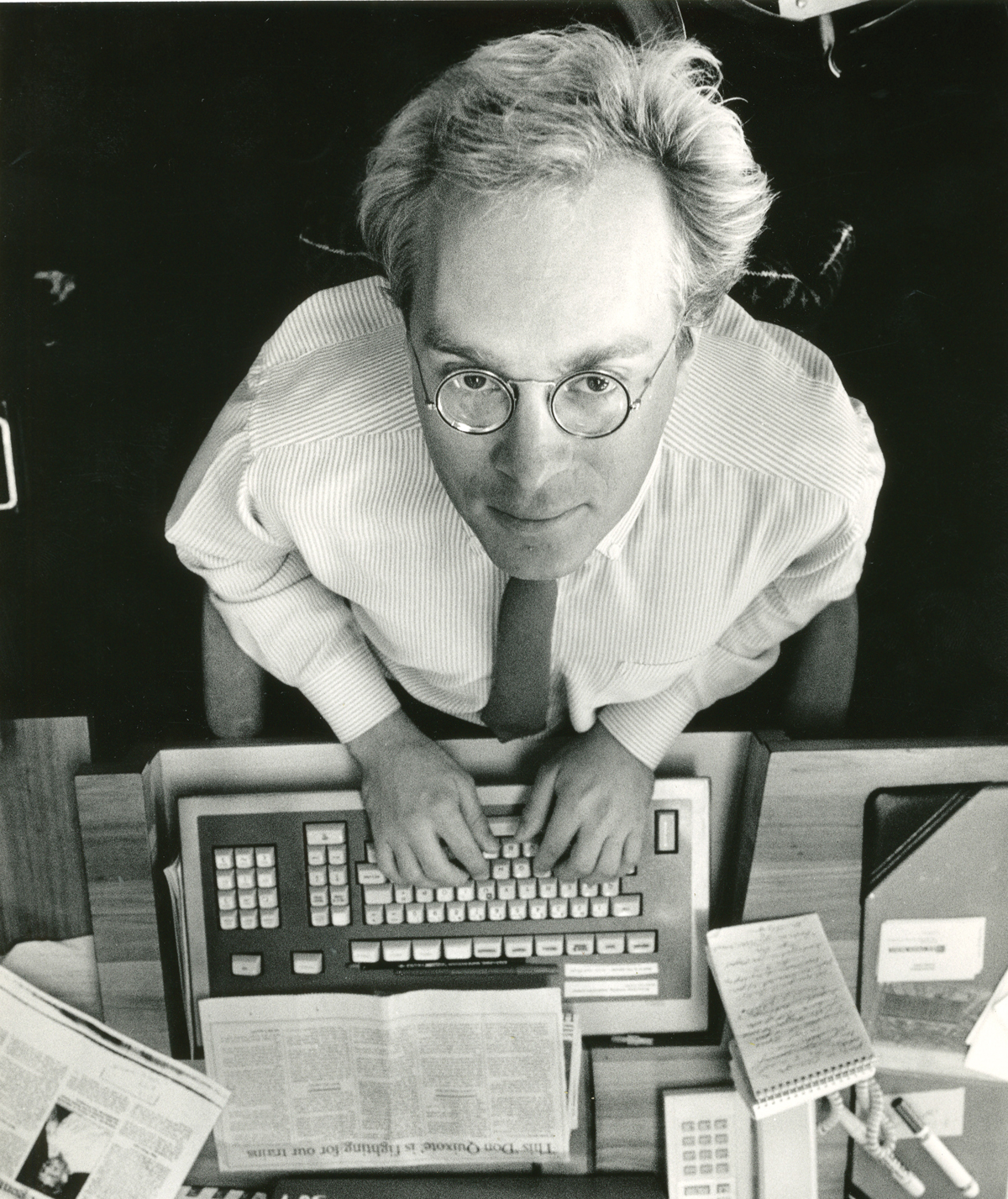

When I enrolled as a student in the university’s Historic Preservation program (Class of 1992), I arrived fresh from a decade-long job as a reporter for the Toronto Star (a paper I would return to in 1997), where I had learned a thing or two about how readers react to media coverage. Response often seemed out of proportion: you could write something as filler—“Alf, we need five inches for the Metro page”—and some people, especially politicians, would imagine whatever you wrote to be an outbreak of public clamour. This could seem absurd, but it also showed the possibilities for getting things done: The Star Gets Action, as the paper often boasts.

To that Vermont class I brought lessons from the reporters’ trenches, such as the small item I wrote about the languishing of the old Eaton’s event space atop College Park in downtown Toronto. That brief led to several stories that reignited an old debate over the space’s future. I remember at one point having an appointment to meet Eleanor Koldofsky, the former wife of the record king Sam Sniderman, in an underground garage, where she handed me a proverbial brown paper envelope stuffed with documents about promises made by developers to restore Eaton’s Seventh Floor. Years would pass but, eventually, the French architect Jacques Carlu’s beautiful streamline moderne space would be restored—a back-to-glorious-original restoration not usually seen in Toronto.

As I told the students, we had more, and perhaps more broadly significant, success reporting on Toronto’s street lighting system. In the early nineteen-nineties it was apparent that Toronto’s old incandescent street lights were consuming too much energy, but people in the urbane (pre-amalgamation) city of Toronto had also noticed how nice, comfortable, and even safe Toronto looked under their creamy white, old-fashioned light.

It seems, at first glance, like an esoteric detail in a city’s life, but this was a quarter century ago, when there was still fear that U.S.-style urban decline would somehow creep up to Toronto. Citizens were defensive when any threat to the urban fabric was perceived. Night in Toronto certainly seemed welcoming compared to most cities, which had adopted, almost as a default, high-efficiency, high-pressure sodium street lighting that painted the street, trees, and virtually everything else an ominous puke orange. Even so, the orange technology was being pushed hard as an energy saver by the huge industry that makes millions of roadway light poles, fixtures, and bulbs installed and operated at public expense virtually everywhere in the world.

But could you get good light and low energy consumption? I wasn’t yet working at the Star again, but somebody asked the question, and the newspaper duly covered an ensuing public debate, into which I was pulled. Fresh out of preservation school, where I’d written an essay on urban street lighting, I got myself onto Toronto’s street and lane lighting subcommittee as a citizen member.

Howard Levine, a city councillor who was something of a renegade, led the committee and the discussion, which was finally a battle of “big lighting”—represented at the city level by Nick Vardin, then the commissioner of public works—versus the committee on which I sat. (The committee also included other citizens, N.D.P. Councillor Peter Tabuns, and several veteran engineers from the municipally owned Toronto Hydro, who, as insiders in the industry, felt the providers had lagged in improving lighting technologies and needed a kick in the pants.)

As I told the students, there were several media-related tipping points in the conversation, without which I doubt Toronto would have proceeded to adopt a more progressive white-light technology. At one point I used my old contacts at the Star to get an op-ed piece I wrote published. In it, I laid out the dilemmas in as plain-but-interesting prose as I could. The nature of night in the city is, in its own way, a flashpoint, concerning as it does perceptions of safety.

Meanwhile the citizens’ committee filed its report, having learned of clear-light technologies in use in Europe; a recommendation to try it went to council and finally came up for a vote. Around the same time, an editorial appeared in the Star, under the headline WHITE LIGHTS FOR THE BIG CITY. It crisply parsed the arguments on each side, with the paper supporting the idea that this new European technology was more in keeping with Toronto’s citizen- and neighbourhood-friendly city-building policies. The vote was close, but the policy was adopted. The plan was implemented over the next two years, when a new street-lighting system, much resembling the old incandescent one and pioneering the use of new white-light technology in North America, was installed across the city.

The appearance in the U.S. of Fox News, whose aggressive biases had, by the turn of the century, made the ancient given of social control in the newsroom more apparent to the public, may have been behind my class’s obvious and expressed skepticism of a lot of what I said that day. They were skeptical of my rosy account of media power—theirs was the natural and needed defense mechanism in a world of uneven and often suspect coverage.

Perhaps I was the naive one, raised in Canadian journalism and having spent, until then, most of my career at the Toronto Star. It’s not that the Star is any less a part of Canada’s establishment than U.S. media is of America’s. It is always tempting, when suggesting the Star is different, to point to the newspaper’s famous Atkinson Principles—the idea that little folks deserve a fair shake in newspaper reporting, though the case could always be made that these principles are more good business than enforced policy.

But the thing is—I say now, having recently left the Star after working there for the better part of three decades—the journalists themselves take those principles very seriously. For many of us, the principles drew us to the paper; we detected them in its coverage. Once hired, reporters seized them as an enabler for their feral tendencies—something to leverage to justify rabble-rousing, Star Gets Action stories. Those stories continue to resonate. People still say to me, on learning of my connection to the Star, that “the paper” does good work.

My personal experience lay behind my talk at the University of Vermont. To the class, I must have sounded like an earnest Boy Scout. I recall feeling disappointed: not in them, but that they had delivered a grim reality check to an Atkinsonian idealist from Toronto.

My revered professor, Thomas Visser, never mentioned the students’ reaction, if he noticed it, and I don’t recall seeing any assessments of my presentation. My own analysis, in hindsight, is that they were right to be skeptical. But then I think about all that action achieved by the Star, in the time I was there and before. Newsrooms are never easy places to work. But journalists do their best when they are feral, and that’s what we were, all those decades, not uniquely or exclusively, but classically. Journalists who, whatever control systems they worked under, were kind of out of control, in a good way—teeth clenched at injustice and, paradoxically, hearts at least partly filled with empathy and even kindness.