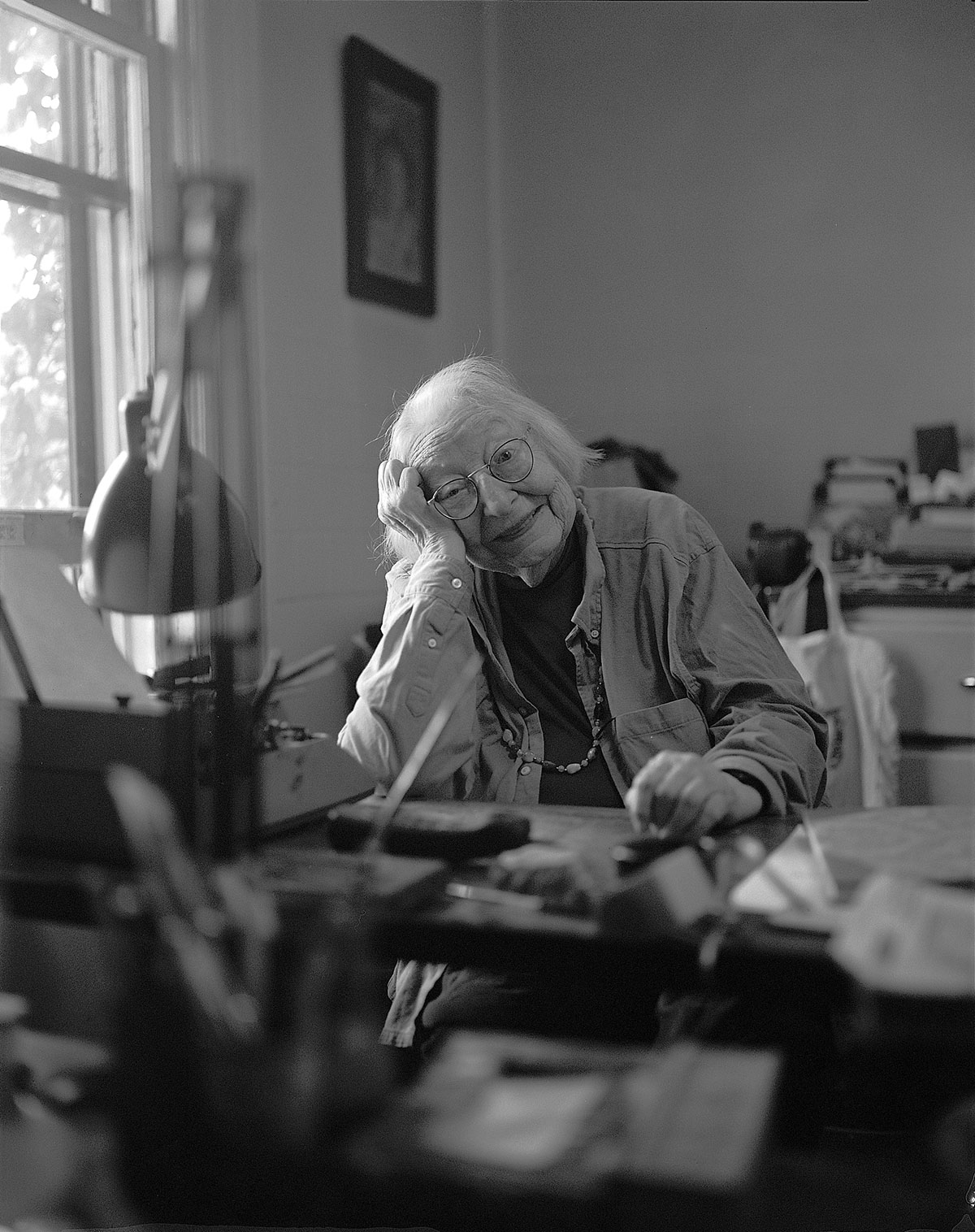

Jane Jacobs writes her books in an upstairs room at the back of her house, on Albany Avenue, in Toronto’s Annex neighbourhood. There is a countertop across the south wall—now piled with odds and ends—suggesting the room was once a kitchen. The desk is cluttered with writers’ flotsam: cups filled with pens, knick-knacks serving as paperweights, and, of course, paper.

“Somebody has given me their L. C. Smith that they’re through with,” says Jacobs, seated at her desk in front of the now ancient manual typewriter. “I keep the top off because the ribbon reversal doesn’t happen automatically anymore, and so I have to keep an eye on when it’s getting near the end….It’s hard to find typewriter-repair people anymore.” No author still producing books at the age of eighty-eight needs to make excuses for using old technology, but Jacobs, the long-time critic—and ally—of cities offers some thoughts. With a computer, it’s so easy to change what you’ve written, she says. “And I don’t think it’s all to the good. It’s so easy to add, that it breaks down the discipline of organization.”

“How does the process work for you? ” I ask, playing for useful advice.

“Well, very much trial and error, and I fill up my wastebasket with false starts,” Jacobs responds, unhelpfully. “And—I’m a very, very slow writer. When I keep making mistakes and keep filling up wastebaskets and wasting paper, I know the trouble is organization somewhere. And yet I don’t seem able to solve that without just trying. I don’t object to writing something over again because it’s harder or takes longer than with a computer because, somehow or other, manual labour helps me.”

In this corner of the old house—where I visited Jacobs this past May—is a single double-hung window, looking east into typical overgrown Annex backyards. Here Jacobs, at her L. C. Smith, has breakthroughs (she calls them “earthquakes”)—when ideas flow and progress is swift. She wrestles with oft-remade outlines that are “as much hindrances as helps.” She struggles to gather disparate thoughts into what Naomi Bliven, Jacobs’ friend, the former New Yorker reviewer, called “genie chapters.” These are, perhaps, equivalent to the newspaper editor’s cherished “nut graph,” where key threads in a tale come together and jell for the reader.

“Now, in your latest book, have you perfected your writing processes? ” I ask. “Is it somehow easier? ”

“That one was easier, I don’t know why. And quicker. Ah, but I don’t understand these things,” says the author of seven books. “If it comes more easily and quickly, I’m just grateful for it. I don’t think it means… the next one will be.”

Jacobs mentions the “long, difficult dry period” between The Economy of Cities, published in 1969, and 1984’s Cities and the Wealth of Nations. “I did write a great deal,” she says, adding with a chuckle, “but most of it was garbage.”

“There’s no magic elixir? ” I ask.

“I wish I knew what it was.”

Dark Age Ahead, Jane Jacobs’ latest book, was published on May 15, 2004, and pulls the zoom lens she first focused on the streets and sidewalks of Greenwich Village, in the groundbreaking 1961 urban bible The Death and Life of Great American Cities, back, back, back, until a vast, interconnected global landscape comes into view. One of Dark Age Ahead’s lead characters was again the author’s hometown: no longer New York but long since Toronto, the great city that had done much right—in no small measure in response to her writings—until new forces began chipping at its foundation. As Jacobs describes them in Dark Age Ahead, those forces were amorphous—vague things like slipping discipline in learned professions—and specific, such as an amalgamation of municipalities that left the city with huge responsibilities and insufficient powers to fulfill them.

Jacobs’ reporter’s eye was honed from working at her hometown Scranton Republican, sharpened for city life in the postwar era as an editor of Architectural Forum, and shown dramatically to the public in a landmark article, “Downtown is for People,” in the April, 1958, issue of Fortune. The Death and Life of Great American Cities began with disparate, seemingly trivial data literally culled from the cracks and crevices, hydrants and manhole covers of Hudson Street and constructed an incisive and ultimately vindicated exposé of city-building policies at the highest level, namely urban-renewal practices that were in fact destroying cities. Now she reverses the mould, tracing circumstances back the other way, sifting through abstract, impersonal policies and vast bureaucracies of government, business, and academia for roots of grimy problems such as homelessness and family poverty. In 2004, as in 1961, the iceberg effect held: what was initially visible hinted at broad, more universal dangers and turnings.

If its message is ultimately more dramatic—anxiety over the future, not just of cities, but of civilization as we know it—Dark Age, despite its title, has a surprisingly gentle, prescriptive, even hopeful nature. “Until we get into irreversible trouble, which a culture can, everything that’s done right has the advantage… of connecting with everything else,” Jacobs, in a voice leavened, now by default, with a grandmother’s wisdom told me. “So you don’t have to change everything at once.”

But the change Jacobs is advocating would involve more than rearranging deck chairs. As she writes in Dark Age Ahead, there is in Canada a measure of understanding at those high-policy levels—whose broad-brush decisions, she argues are the root of some very down-and-dirty problems—but not much appetite for reform. In the United States, preoccupied with pre-emptive attacks of a more military nature, there appears to be no understanding at those levels whatsoever. Reports such as one that went out over the wires of the Associated Press a few weeks after the launch of Dark Age Ahead can’t have seemed to very many people anything more than esoteric electrons on a dull subject: “The state takeover of Flint’s finances may be nearing an end,” the press agency reported in an item following up on the Michigan city’s 2002 financial collapse. “The decision means emergency financial manager Ed Kurtz will relinquish power to Mayor Don Williamson and the City Council….Kurtz has eliminated 300 city jobs through attrition and layoffs, reduced the amount spent on overtime pay, cut the mayor’s and City Council members’ salaries and angered residents by cutting funding for five neighborhood recreation centers.”

Flint was the city that hoped to recast itself as lively Toronto—at least as told, tongue in cheek, in Roger & Me, the director Michael Moore’s 1989 film debut. And now Toronto and Flint did share a predicament. In Ontario the massive rearrangement of powers undertaken by the Mike Harris Progressive Conservative government in the nineteen-nineties shifted major responsibilities—portions of them or the financing of them—to the province’s cities in such areas as public transportation, housing, and education. The expression “revenue neutral” was used to describe how resources would still be sufficient, but perhaps intentionally, it hadn’t panned out. In practice, long-established revenue-generating powers were taken away. These included the ability to raise money for education through property taxes, itself an archaic system that failed to mirror growth in economies, but better than nothing and at least transparent to taxpayers. There was much unhappiness in the bigger Ontario cities; in Toronto, Hamilton, and Ottawa school trustees defied provincial orders to balance their budgets, now assigned by the province, by making huge cuts to school operations. Like the burghers of Flint, elected officials found their powers suspended, their offices and duties taken over by politically approved appointees.

The learned and decorated Ursula Franklin, a University of Toronto professor emeritus and Companion of the Order of Canada, felt the cuts were a deliberate grab of power by the feudally or fascistically inclined. “As I see it, they are trying through structural changes to permanently decouple citizens from local politics and, using their legislative majority, turn local government into local administration,” Franklin wrote in her 1997 essay, “Citizen Politics—New Dimensions to Old Problems: Reflections for Jane Jacobs.”

Jacobs herself was much more circumspect. As in 1961, she put on her glasses and looked around for parallels and precedents and connections that, more than theory, rhetoric, or ideological fashions, might explain what was going on in Toronto, in flagging Flint, in New York (where Mayor Michael Bloomberg faced a five-billion-dollar deficit in 2002), and elsewhere. Signals could be found—some of them oddly ancient yet so applicable they startled. “In the last desperate years before Western Rome’s collapse,” Jacobs recounts in Dark Age Ahead, “local governments had been expunged by imperial decree and were replaced by a centralized military despotism, not a workable organ for governmental judgments and reflections.” Not unlike the Roman guard units, who took new powers hoping to enrich themselves, the Ontario Tories duly distributed the gain in the form of tax breaks, which accrued most efficiently—ironically, but not by accident—to those with the highest incomes. Such were the books managed that the provincial government itself, in addition to the major Ontario municipalities, was mired deep in deficit at the time of its defeat in 2003.

In the current decade, as the movers and shakers who benefited from the tax cuts tooled about in premium cars and S.U.V.’s or contemplated which plasma TV to buy—all the while complaining about inadequate public schools, litter, potholes, and profligate poor—could Jane Jacobs be blamed for contending that Rome was burning?

The term “pillar of the community” is self-explanatory, but the concept doesn’t apply only to revered citizens. “The spirit of truth and the spirit of freedom—they are the pillars of society,” wrote the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen. In Dark Age Ahead Jane Jacobs writes about pillars of our civilization, referring to the broadest, most basic underpinnings of modern culture and commerce. She argues these pillars are deteriorating. An apt, physical city-building analogy might be spalling: attacked by acid rain, freeze-thaw cycles, and time (and sometimes more nefarious forces than neglect) the hardest stone turns to flakes, the greatest columns to dust.

The fatalist would be resigned, the preservationist alerted, and Dark Age Ahead is for both. Dark Age Ahead devotes a chapter to each of five pillars and why they are failing, concluding the book with a chapter offering ideas for remediation. Fundamentalists of various brands—libertarians, bible-thumping zealots, family-values types, Republicans, former Reform party supporters, officers of the Fraser Institute think tank—might perk up at the list. Jacobs’ endangered and vital pillars are the institutions of family and community; the responsible practice of science and technology; tax policy and government “directly in touch with needs and possibilities”; education—mainly post-secondary, but Jacobs has a lot to say about the neighbourhood school; and what the author terms “self-policing by the learned professions.” Those on the political left will be disappointed that many of their priorities—“such failings as racism, profligate environmental destruction… low turnouts for elections, and the enlarging gulf between rich and poor”—are not listed among the pillars but rather as symptoms of breakdown.

But Jacobs doesn’t hold ideologies and abstract theories too dear, and the reader won’t find her wisdom to be generally conventional. In the Dark Age Ahead chapter “Families Rigged to Fail,” no fault is found with homosexual marriages, insufficient churchgoing, or polyglot households—they might offend some, but seem to work: “This world contains households with enormous varieties of members: concubines; apprentices and other students; roomers and boarders.” The family pillar is weakening under many other pressures. One is financial, an unfavourable “shelter equation” where the cost of housing, whether rent or mortgage, is consuming too much for too many, “leaving too little for everything else.” Jacobs suggests a range of assisted housing would go a long way toward mitigating the problem, but the option no longer seems to exist in public policy. Perversely, money that might help the situation, directly or indirectly, is being returned as tax cuts to the wealthiest citizens, who don’t need it.

Some phenomena erode different pillars at once. Car-driven sprawl has superseded more human-scaled business districts and neighbourhoods, as it has eaten farmland, as it generates pollution, as running-costs of cars are among the pressures that eat at families’ abilities to meet other needs. “Cars again!” admonished Bruce Ramsey in his May 2nd Seattle Times review of Dark Age Ahead. “[I]f Jacobs wanted to write about cars… she should have done it openly and not disguised it as a book about the eclipse of civilization.”

But Jacobs, among others, feels the two are connected, which itself seems like an understatement. The sprawling urban form automobiles begat—at least in North America—has transformed much: the landscape, the environment, the family. Among many factors, family togetherness in vehicles might be measured against driver tedium, lack of exercise, and delayed advancement of certain adult skills. “I walked to school when I was a youngster, unattended,” I tell Jacobs. “I did, too,” she says. “Or, usually, I roller-skated to school.”

“What does it mean, when kids don’t learn the transit system? ” I ask.

“Just sitting there in the streetcar or whatever vehicle it is, looking at the other people, you see they aren’t monsters,” she says. “You see that they’re going to work the same as you are, or going job-hunting. You see that there are all kinds of people. These everyday connotations of life are important. I’ve known people who wouldn’t go on the subway or a bus because they’re afraid to. And that’s a very bad breakdown.”

Reviewers, each in their day, quibbled with the titles of Jacobs’ books. “Take the title itself, The Death and Life of Great American Cities,” declared a writer in the May, 1962, number of the planning magazine American City. “Obviously no great American city has died.” (Then and now, one could argue the point.) “Dark Age Ahead is a pretentious title for this book,” wrote Ramsey in the Seattle Times. “A title this far off from an author this famous cannot have come from the publisher. It must be hers.” A bigger question raised by the critics: Was the author living up to her responsibility to the reader? Jacobs acknowledges she did not raise all the questions, make all the connections, or provide all the answers. Humility is a virtue to some, a fault to others. “[T]hese discussions are cursory in the extreme,” wrote Michiko Kakutani in a particularly devastating critique in the New York Times, finding it all hard to grasp. “Despite its Cassandralike title, this book reads less like a convincing wake-up call than a collection of random jottings, glossed with unnecessary daubs of hyperbole and only occasional flashes of vintage Jacobs insight.” The book’s critique of auto-driven city building set people off. There were “many startling, intriguing ideas to be quarried from its pages,” wrote David Evans, the opinions-page editor of the Edmonton Journal, finding in the end that the book seemed “more likely to provoke irritation than anything else….The current writer, for example, is from Toronto and devoutly believes in public transit and walk-everywhere neighbourhoods.” By about page fifty, Evans felt like “buying a big diesel pickup to take home and drive past all those trendy shoppes and yuppie infill duplexes.”

Those with long memories—Jacobs herself now, surely—will see the similarities between the reception accorded Dark Age Ahead and that given Death and Life. The latter pushed the envelope of what people were ready to understand about cities in 1961. It angered the movers and shakers then involved in urban renewal. Among those rankled was the then-reigning guru of city building, Lewis Mumford, whose six-hundred-and-fifty-seven-page The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects was published almost simultaneously with The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Imagine the stern scholar in a bookstore, in 1961, comparing the two dust covers (no pictures, similar typeface) as they sat side by side on the new-releases shelf. Mumford, too, had reservations about clear-cut urban renewal, but he was a theorist and an academic. His heavy volume, which delved deeply into ancient history, was a vital account. But where Death and Life delighted in the city, Mumford had a more sober view of cities as an intractable problem. He was cordial to Jacobs in personal letters to her, but to others called her “a confident but sloppy novice.” By 1965 he went public with a measure of contempt. In one review of a book about early planned cities, he refers to “Jane Jacobs’s preposterous mass of historic misinformation and contemporary misinterpretation in her The Death and Life of Great American Cities” that, he wrote, “exposed her ignorance of the whole planning movement.”

Jacobs would, within a decade, topple Mumford from his throne, but for now it appeared no one was listening to either writer. Clear-cut urban renewal remained the way planners and developers sought to move communities into the future—the only way, apparently, they knew. The term “historic preservation” did not seem to exist; any concept of the rehabilitation of urban fabric existed only on the margins. On May 17, 1966, a full five years after The Death and Life of Great American Cities was published, reviewed, and dismissed by those with the most power to change directions, demolition crews started hacking at 27–33 Champlain Street, in Burlington, Vermont, to begin clear-cut demolition of twenty-seven acres of the city’s mixed-use downtown. It was a case right out of Jacobs’ book: a neighbourhood officially declared a slum to become eligible for federal urban-renewal funding and seized by eminent domain. On closer inspection, the neighbourhood had much good architecture, many thriving businesses, and an ingrained community life, and by this time it was surely clear that physically eliminating places couldn’t eliminate problems. But residents’ earnest and at times angry protests failed to move the project’s developers (who stood to lose much, and would) or city fathers, and demolition of a major swath of the city went ahead. The detached box-like buildings that were constructed sporadically over the next generation failed to produce thriving businesses or generate neighbourhood vitality. Investors lost interest long before the area achieved a critical mass of any kind. The project failed and, almost forty years later, in 2004, the most publicly visible lakeside property in an important New England city remains underdeveloped.

But if the detailed messages of Death and Life only simmered in the nineteen-sixties, the sprawling automotive landscape was being noticed. In 1964, Peter Blake, managing editor of Architectural Forum—the trade journal where Jane Jacobs had worked—published God’s Own Junkyard, explicitly illustrating how the era’s shopping centres, motel strips and gas-station alleys (which, interestingly, now look quaint and welcoming beside today’s exponentially vaster highway strips) were conquering pristine landscape.

Motor vehicles and North American life seem so interconnected at so many levels that not to deconstruct their impact would be to tell no story. In Dark Age Ahead, Jacobs identifies how the Great Depression gave rise to widespread support in North America for substantial, active policies to ensure full employment. Such policies were driving forces behind such monumental projects as the United States interstate highway system, one of the largest construction projects ever undertaken, whose transformation of the transportation system gave the auto industry an easy ride—perhaps too easy. Jacobs notes that the U.S. auto industry has failed to lead the business, its profits riding increasingly on fads such as S.U.V.’s, which essentially recycle existing low-tech pickup-truck technology. They have failed to innovate as major foreign automakers have, particularly the Japanese, who pushed the U.S automakers out of the backbone of the market for small and mid-size cars.

In the nineteen-eighties, the Washington Post reporter Joel Garreau hit the road to find out just what community was out there on the sprawling edge. In Edge City, his resulting urban manifesto, he challenged the ideas presented by Jacobs, among others, finding real community in surprising places—mostly indoors, off parking lots—but community nonetheless. One example he gave was the seafood counter at the Yaohan Plaza in Fort Lee, New Jersey, where “for eighty linear feet, it spreads out not only six different kinds of sliced octopus—fresh—but snow crab legs next to broiled eels near Chilean abalone next to geoduck sashimi, adjacent to a display of spiny sea urchins with golden, creamy, sensuous interiors intended to be eaten raw.” Lovers of big cities often remark on the array of choices a large population will support; this Japanese-flavoured shopping centre made the point that there was life, and choice, and even multiculturalism, out on the edge. “Give Edge Cities time before you lose your composure,” Garreau wrote. Yet he admitted it was physically disparate, disconnected culture, focusing on indoor pockets and corporate campuses. It wasn’t a complete, satisfying environment—a promenade on the Champs Élysées, an afternoon shopping in London, a ride on Toronto’s Queen streetcar. Looking around he still had to write: “If Edge City is our new standard form of American metropolis—if Edge City is the agglomeration of all we feel we want and need—will these places ever be diverse, urbane, and livable? Will our Edge Cities ever be full of agreeable surprises? Will they ever come together gracefully? ”

Could the case that there is insidious decay in such diverse things as sprawl, in accounting scandals and impropriety in trusted professions, in cuts to funding for public education that shortchange university students of wisdom, or in corruption in science, have been better put in Dark Age Ahead? Jacobs wondered herself. She urged people to join her grappling with the monster—the amorphous, interconnected issues that almost defied grappling with. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., commented that living “calls for great and combined intellectual efforts.” Jane Jacobs wrote in Dark Age Ahead, “I can only apologize for being less omniscient than I should be as I take up a responsibility—which I hope readers will also assume—for trying to do the small bit I can to give stabilizing correction a push.”

It was gently put, considering the topic and the message. But inevitably, as it did in 1961, the rocking boat made many feel scolded, miffed, affronted. “Dark Age Ahead is a good example of the crumbling of a sixth key pillar of civilization that Jacobs fails to mention: the ability of would-be opinion leaders to communicate persuasively with people who don’t agree with them,” wrote the Edmonton Journal’s Evans. Nonetheless, out there on the car-driven Canadian Prairies, Dark Age Ahead was propelled to No. 2 on the Journal’s bestseller list and ranked in the non-fiction Top Ten throughout Canada for most of the summer of 2004.

From the left side of the political spectrum came a critique from the artist and compulsive letter-writer Mendelson Joe, who “escaped” Toronto for the nearby Almaguin Highlands in 2000. “Jane Jacobs is about two decades too late with her ‘plea for us to awake in time,’” he wrote me in response to my May 16th review of Dark Age Ahead, published in the Toronto Star. On the back of a postcard of one of his paintings showing a landscape of fume-spewing vehicles rushing toward a brown sky, under a fume-spewing helicopter, Joe wrote, “We are pathetic self-centred slobs who hate our children.” He may have been right. But were his pictures getting the message out?

Milton wrote, in the style of his times, “when a City shall be as it were besieged and blocked about, her navigable river infested, inroads and incursions round, defiances and battle oft rumoured to be marching up even to her walls, and suburb trenches, that then the people, or the greater part, more than at other times, wholly taken up with the study of highest and most important matters to be reformed, should be disputing, reasoning, reading, inventing, discoursing, even to a rarity, and admiration, things not before discoursed or written of.”

This tract from Areopagitica is considered one of the founding essays of free speech. It is, today, inscribed in gold lettering around the perimeter of the Great Hall in Hart House at the University of Toronto, where a roomful of smart people interested in the welfare of Canada’s largest and most unfortunately besieged city—and in other cities, too—gathered on June 21st to confer and debate Dark Age Ahead. The guest of honour: Jane Jacobs, of Albany Avenue, this day dressed in a lavender shirt and black slacks, her trademark papier mâché ear horn at the ready.

Other guest speakers were primped and prepared, and sprinkled through the audience, seated in the hall’s sturdy straight-backed chairs, were various champions of the city. Over in a front row, David Crombie, former mayor of Toronto, the Conservative politician under whose watch the last renaissance of the city took hold in the nineteen-seventies. Seated near him was Anne Golden, former chief of the United Way, who in the mid-nineteen-nineties penned a governance plan for Toronto-region municipalities that argued they needed more, not fewer, powers to thrive. Over there by the stained-glass window, smiling and chatting as always, was the bow-tied John Honderich, just stepped down as publisher of the Toronto Star. Canada’s largest newspaper had advocated Toronto’s amalgamation, but as the city’s fiscal position spiralled down in the late nineteen-nineties, Honderich made the notion of a new deal for Canadian cities the Star’s crusade. The expression, of course, came from Franklin Roosevelt’s push for reforms in the United States that helped ordinary people during the Great Depression. Its meaning in twenty-first-century Toronto was more literal, calling for new arrangements to bring the city, and by now other major Canadian cities, the powers and income it needed to meet its responsibilities.

But debate is an untidy thing. In full bloom it is like Milton’s sentence on the wall, a haze from which the truths must be coaxed and tested. One of the speakers that day was Robert Lucas, winner of the 1995 Nobel Prize in Economics. While he found much to admire in Jacobs’ economic observations in her book The Economy of Cities, Lucas took issue with the basic message of Dark Age Ahead. “I don’t see the darkness,” he told the Globe and Mail’s John Barber. Like Jacobs, he felt humans were abandoning their agrarian roots, but where she saw decay undermining diverse supporting institutions, he foresaw an era of fabulous growth based on technological advance.

It was a familiar juxtaposition: the theorist versus the pragmatist, the high-octane expert versus the aged bohemian, whose only credential in academia is her track record. “For her part, Ms. Jacobs graciously accepted the criticism and cheered the good news… with its promise of limitless growth in innovative cities,” Barber reported the next day. “‘That pleases me,’ she said from her front-row seat in the Great Hall at Hart House. ‘I hope it’s right.’”

At its heart—tying the five pillars together—seems to be one thriving problem in particular: greed. It has so mutated and benefited from spin and lawmakers serving their own vested interest since the nineteen-eighties that, today, greed is wearing many virtuous masks: thrift, efficiency, necessity, bravery. The greed-packaged-as-virtue champions are extreme political parties such as the Republicans in the United States, the disgraced Harris Conservatives in Ontario, and the ever-morphing Reform/Alliance/Conservatives on Canada’s federal scene. All found a formula for electoral success in a form of Newspeak whereby damaging policy—cuts to education, municipalities, services, safety nets—is presented as reckoning on behalf of ordinary people fed up with government. It was sold with decisive-sounding tough talk, strategic use of mind-boggling numbers or, most effective of all, through complex screens such as tax cuts that let basic mathematical laws do the dirty work. But everyone was promised something with tax cuts, and under that ruse, framed by the thrifty notion of tax reduction as opposed to wasteful bureaucracy and welfare, the burden of running cities and countries was shifted to those who had less, could pay less, and who, arguably, ultimately demanded less, too.

Greed does not figure prominently in Dark Age Ahead. Jacobs more broadly attacks fundamentalism (in whose fold she included neo-conservative politics) as severe dogma that does not sufficiently take into consideration complex realities and the greater good of society. “Neo-conservatives, they had a notion of efficiency, I suppose they still do, as stripping things down to the minimum,” Jacobs says. It is analogous to the individual living close to the line, she suggests. The risks were illustrated by the 2003 sars crisis in Toronto. Years of underfunding of medical infrastructure ended up “leaving us pretty helpless if a disaster came along like SARS,” unable to respond effectively either in the lab or at the hospital. There was no room for “redundancy,” sufficient systems and personnel to back up other systems and personnel in times of crisis, and keep stress at bay in normal times. Redundancy is a misleading word, implying waste, but consider it has long been the cardinal rule in the design of aircraft—systems are duplicated and sets of alternative controls installed to prevent disaster in case one fails. It raises the question: Is close-to-the-line managing not efficiency but, in fact, an expression of greed, where decision-makers seeking shifts to benefit their own constituencies consciously sacrifice the broader good?

So Conservatives won’t be happy with Dark Age Ahead. By the same token, Jacobs finds little solace in the performances of other, more moderate, administrations in Ontario and Ottawa. “A lot of people think the N.D.P. is different from others, but no, it has a history of belief in centralized power and certainly didn’t give it up when it was the government [in Ontario],” she says. Centralization remains one of her bugaboos because, she says, it results in “one size fits all” policies that ignore local conditions. Canada’s best governments in recent decades have been minority governments, she says, arguing they fostered a brokering and bargaining that cut through the tendency of majority-governing parties to pursue policies serving one ideology.

So opinionated, yet so gracious; what a dimension it adds to reckoning about Jane Jacobs. Those with a difference of opinion can’t get mad at her for saying she’s right, as she takes pains to say she may not be. Surely maddening is the record—the haunting rightness of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, against which Jacobs and Dark Age Ahead must now be measured in the context of different and extraordinarily troubled, complicated, and brutal times. It is one thing to make an airtight argument, fully reasoned, complete, and utterly persuasive, that reviewers embrace on a biblical scale. Harder is to grapple—on scales impossibly large—with the directions of an age and to discern comprehensible patterns we can learn from.

I interviewed Jacobs again in September, this time in front of a sold-out crowd at the Harbourfront Reading Series. Jacobs told the audience it took a generation for the ideas in Death and Life to have impact. Can we expect the same of Dark Age Ahead? Probably, she said.

“Do we have that long? ” I asked. She wasn’t sure.