Dale Brazao awoke to the sound of a backhoe making noise “so loud my house shook.” Investigating the children’s playground next door from his kitchen window, he was startled to see “this man at the controls of a Caterpillar,” using the bucket to rip apart the Jungle Gym in the yard of Williamson Road Junior Public School, in his east-end Toronto neighbourhood near the Beach.

“I ran out, and there was a bunch of little kids hanging onto the fence, watching,” Brazao, a veteran newspaper reporter, remembered. “A couple of them looked to be seven or eight years old, maybe in Grade 1 or 2. You should have seen the look on their faces.”

It was near the end of the school year, the third week of June, 2000, and Brazao was witnessing what became a moment of infamy or, depending on your sensibility, of redemption in Canada’s largest metropolis. No, this wasn’t some rogue heavy-equipment operator—nothing like the madman who briefly terrorized an Etobicoke street with a bulldozer in the late nineteen-eighties. Nor was it a mistake, although many wondered—including the backhoe operator himself, an employee of Priestly Demolition who, remembered Brazao, “seemed to be expressing some doubt” as he took most of the day to pry apart the adventure playground, a huge Jungle Gym, thirty feet long, with a playhouse, stairs, netting, a slide, and monkey bars.

Any doubt that the hapless backhoe operator, the grimacing kids at the fence watching him, or journalist Dale Brazao shared that day would soon be passed on to thousands more. In the coming weeks, the Toronto District School Board, the largest educational institution in the land, ordered the demolition of play structures at public schools across the amalgamated city. “They loaded the pieces onto a truck and took them away,” said Caz Zyvatkauskas, the parent of a student at Orde Street Junior Public School, in the heart of downtown Toronto.

“[T]he other day I was over at Bedford Park and saw two pieces of heavy machinery and a dump truck at work,” Jim Coyle wrote in his Toronto Star column on August 10, 2000. “When they were done, all that was left of the playground was a sandpit, the wooden perimeter, and two small concavities worn in the ground beneath what was once the tire swing.”

The demolition had no parallel in the history of Ontario education. By the time school reopened in the fall, playgrounds, or parts of them, had been razed at a hundred and seventy-two out of four hundred and fifty-one elementary schools, their names stretching from one end of the alphabet to the other, from Adam Beck to Withrow Avenue. Given such numbers, perhaps it was inevitable that a demolition crew would show up, crowbars in hand, at the wrong school. “It’s not yours anymore,” Patrick O’Brien, a janitor at École Élémentaire Félix-Leclerc—long since transferred to Toronto’s French public school board—told a couple of men who arrived in a pickup truck. He guarded the targeted adventure playground until the crew double-checked its list, got back into the truck, and drove away.

The demolition bill came in at seven hundred thousand dollars. One estimate placed the replacement cost at $27.5 million. Yet the reason for the demolition was, surely, the redemption part of this story: safety. “[T]he Toronto District School Board (TDSB) has removed equipment deemed a serious hazard to children,” read the introduction to an upbeat F.A.Q. posted to the school board’s web site that July, as the demolitions picked up steam.

In the F.A.Q. document, the board reviewed events leading up to the 2000 tear down: the September, 1999, revision of Ontario licensing requirements, apparently mandating that playground equipment used for child care centres (many hosted by Toronto schools) meet new supposedly voluntary Canadian Standards Association requirements; the subsequent and detailed third-party audit (such party being Jeff Elliott Playground Safety Inspections, based in Waterloo, Ontario) which found, virtually everywhere, tripping hazards, loose bolts, places to get stuck, deep pits below tire swings, and such sandbox threats as “head entrapment between seat and side rails.” The F.A.Q. might have mentioned, but did not, the “advisory” from the worried Ontario School Boards’ Insurance Exchange. The co-operative agency suggested that the new C.S.A. standards, though not mandatory, should be met.

Under the circumstances, did school officials have any choice but to call in Priestly? “We acted morally, ethically and financially responsibly, recognizing the best advice of our experts,” said Shelley Laskin, the school board’s chair, in September, 2000. “We acted to prevent.”

The safety mantra did not resonate. Public opinion was divided. “Penny Smith, a parent with McMurrich Junior Public School near Oakwood Ave. and St. Clair Ave. W., applauds the swift action,” said one report in June. Yet, as the summer wore on and the equipment at playground after playground was trucked away in pieces, a certain incredulity registered at public meetings and in the letters pages of Toronto newspapers. Joy Kaufman, of North York, wrote to the Star, “The decision to destroy playgrounds at schools across Toronto has to be one of the most short-sighted and mean-spirited decisions seen in this city in many years.” That September, Kristin Rushowy, the paper’s education reporter, wrote, “[A]s the dust settled on the mounds of dirt where playgrounds used to be, some angry parents started asking questions.” Theories were batted about. Jane Mercer, of the Toronto Coalition for Better Child Care, blamed the tear downs, ultimately, on the Ontario Ministry of Community and Social Services, which “opened up a Pandora’s box” when it ostensibly required daycare centres meet the C.S.A. equipment standards. Since most schools also have daycare centres, it was game over for their playground equipment, she reasoned. Others cast a suspicious eye toward Marguerite Jackson, who, as director of education, was the Toronto District School Board’s top bureaucrat. Critics of the provincial government were certain Jackson was the Trojan Horse of Ontario premier Mike Harris, the one-time teacher turned education budget slasher. Jackson’s mission, this scenario held, was to maximize chaos in the public school system, contributing to the public’s lack of confidence in it, thus building support for tax credits (in fact established in 2001), vouchers, and other incentives to send students to private schools.

Whatever the truth in such theories, they did not catch the public’s attention any way like the emerging facts of the case did. A key tipping point was September 5th, the first day of school. That day, said Cheryl Moscoe, a parent of two at Faywood Public School, “Everyone was standing around, staring at this hole in the ground” where the playground wasn’t. Meanwhile, the person responsible for writing the C.S.A.’s 1998 standards had been tracked down and found to be none other than the board’s own Mike Jones. Jones was a civil engineer, retired after working for the school system thirty-three years, where he had overseen the design and evolution of playgrounds. Far from being delighted that his standards were being enforced by his former employer, he was adamant, angry, indignant; the Toronto board and its trustees had got it wrong. Yes, the standards raised the bar for playground safety on new equipment; no, they did not somehow make existing playsets instantly unsafe. “Never, never, never,” Jones told a reporter. “Nobody [on the C.S.A. committee] ever imagined this would happen.” The man seemed to be kicking himself, too, for it had been he, while still in the board’s employ, who had been a part of a 1999 task force on “playspace renewal,” which, on one hand, had set in motion the board’s reckoning but, on the other, had urged an altogether different course of action.

Jones’s earlier document had recommended, for the Toronto public system’s hundreds of school playgrounds, something akin to an airline fleet renewal program—a gradual upgrading that, over time, would have seen older equipment given greater scrutiny and, when necessity required and economics permitted, replaced with new. The recommendations “recognize that the playgrounds are not going to last forever, and we should be putting money aside to replace older ones and the ones that become un-economic to maintain,” Jones said. But like those nineteen-sixties-era Air Canada DC-9s, whose performance record was stellar in 2000, the playground equipment was safe.

Not much came of the task force report, and when playground demolition began suddenly in June, 2000, no money was set aside for replacement, nor had a stick of equipment been specified or ordered. This fact, too, proved a tipping point in the court of public opinion. “Parents hammered me,” acknowledged Sheila Ward, a downtown trustee. “[They said] ‘You didn’t have a plan to replace it, no statistics or data to back up your comment. There’s no history in our school, in anybody’s living memory, of any kind of serious accidents. Where do you get off ripping out the playground and not even coming and telling me and my kids? ’”

Explanations went up on the board’s web site. Public relations staff and sober bureaucrats smoothed things over with sentences like, “Facility Services will be compiling a complete database of the condition of units relative to C.S.A. Z-614-98 and will report to the Board,” and “Facility Services staff will remove the unsafe units at no cost to the affected schools to ensure that no child is placed at undue risk.” A September 5th news release stated, “The Toronto District School Board approved aggressive new plans to replace dangerous playscape equipment with new playground learning environments that promote student learning and physical health equitably at all elementary schools.”

The earnest flow of information didn’t seem to help. The board could not shake off the public’s perception of a stealth operation poorly executed, followed by something like a cover-up—a feeling that the once streetwise Toronto public school board had succumbed to panic, liability chill, a trap set by the Ontario government, or—just as likely—an inability to see things in perspective. “Why now? Why 2000? ” Caz Zyvatkauskas, the Orde Street parent, remembered wondering. “Was the accident rate suddenly high? It certainly wasn’t at Orde Street. The number of accidents went up after they tore the playground down.”

“Youngsters in playgrounds and schoolyards across the city keep the spirit of team sports and achievement alive,” Zyvatkauskas wrote in a letter to Mike Volpatti, a marketing assistant with the Toronto Blue Jays, on May 24, 2001. “We, the parents of children attending Orde Day Care centre located downtown on a Toronto District School Board (TDSB) site are asking the Toronto Blue Jays to consider making a financial contribution…” Versions of the same letter, which went on to explain how the need for money to build playgrounds had come about, were also mailed to Toronto’s other professional sports teams—the Raptors, the Maple Leafs, and the Argonauts. The campaign, during the final weeks of Toronto’s bid for the 2008 Olympic Games, was undertaken on behalf of not only Orde Street, but other schools and daycares in central Toronto, and seemed coolly strategic. If the big sports teams came to the aid of tykes’ playgrounds, would not the public reward the grown-up games bid with just the final show of local public support needed to push Toronto over the top at Olympic headquarters in Lausanne, Switzerland?

Originally, parents weren’t supposed to be so involved, nor did they want to be. “We were all so angry,” Zyvatkauskas remembered. “The school board did this. Mothers shouldn’t have to spend their time fundraising. It’s not right.” Said Sheila Ward, the Midtown trustee: “I have had a couple of parents saying, ‘Not one cookie will I sell to replace this equipment.’” Mindful of this sentiment, the board had posted the question, “Will parents have to pay for the replacement of playground equipment? ” on the web F.A.Q., way back in July, 2000. “No,” it dutifully answered. “Parent fundraising will not determine whether a school receives replacement equipment for their school playground. The Board is committed to ensuring all children attending our schools have access to a safe playground.”

But like former U.S. president George Bush’s famous “Read my lips: no new taxes,” the statement was a play on words. Bush raised old taxes. “It was just so obvious that if you didn’t [fundraise] you got nothing,” Zyvatkauskas said. “The playgrounds that were getting built were the places where the parents had all chipped in.”

In deference to parent anger, fund-raising was to be a nineteen-nineties-style partnership with community leaders eager to be seen doing public good. The school board announced Partners in Playgrounds, a fundraising initiative with membership from local businesses and the corporate sector that was to “challenge corporate citizens to come forward to participate.” When ordinary people asked for money, it was begging, but this way, when successful business people asked, it would be an appeal.

The busker’s outstretched hand was primed with three million dollars of the board’s money, later doubled to six million dollars, the source of which was not made clear in official releases, though it was apparently scrounged from the board’s own renewal fund, diverted from fixing roofs, boilers, and other building repairs. That public money added up to nearly one quarter of the cost of rebuilding about a hundred projects, leaving a third to be raised. As an enticement, contributors were celebrated: “The law firms of Shibley Righton LLP and Hicks Morely have… stepped up to the plate, to make a difference,” a news release reported in January, 2001. It also quoted veteran trustee Irene Atkinson, by this time the board’s chair, saying, “This is a grass roots initiative which is pulling together communities across this city to create an outdoor legacy for future generations. It’s simple… children need to play and communities need living green spaces to enjoy!”

But, in the end, the board did not discourage parental involvement. It was soon clear that fundraising of all types would fall well short. Fifteen months after the tear down began, just $1.1 million—a mere fraction of the total estimated twenty-five million dollar replacement cost—had been raised. The qualified “No” was still up on the web F.A.Q. when parents were ushered formally into the cause with a parent-specific how-to fundraising package, dubbed Playgrounds… It’s Child’s Play, issued by the board. The kit included a hotline phone number to the board for advice, information on giving out tax receipts, and the numbers of trust accounts in which to make deposits. Said Progress Report No. 1: “Many School Councils raise funds to support their schools and many communities are doing just that for their local playground.”

Neighbourhoods differed greatly in their fundraising potential. “We didn’t have any parents who had $10,000 to throw,” Zyvatkauskas remembered, hence her letters to the sports teams, all housed in downtown Toronto facilities not far from Orde Street. Catherine Moraes, the board’s senior manager of business development, reported Nelson Mandela Park Public School, on working class Shuter Street, got a thirty thousand dollar donation from the Ontario branch of the Directors Guild of Canada, while Rosedale Junior Public School, in midtown Toronto’s posh Rosedale, had raised close to six figures.

As months passed and new equipment failed to appear, more parents fell in. “We didn’t care, we just wanted our playground,” said Zyvatkauskas, who mentioned in her letter to Volpatti that, “To a three-year-old, this [waiting] represents an eternity.” So long was the rebuild taking at most schools that there were reports of four-square, spud, and marbles making a comeback, more or less with the board’s endorsement. As trustee Gail Nyberg said, “Some of these places had 11 pieces of [playground] equipment. Does a schoolyard need 11 pieces? ” For schools at a loss, “Ms. Nyberg also recommends extra soccer balls and chalk for hopscotch squares,” Margaret Wente reported in her Globe and Mail column. They went one better than chalk at Wilkinson Junior Public School, on east end Donlands Avenue, where the school’s budget committee paid nine hundred dollars to have large hopscotch squares painted on the asphalt.

Parent participation in planning the rebuilding of playgrounds was invited with some fanfare, but interestingly the “suite of options” finally laid out in 2002 by the board in a playground report to parents hardly referred to actual equipment. An “exemplary playground” might include “spaces such as a court, yard, rink, pavement, tarmac, [or] walls.” Or there could be “Natural spaces for play and meeting such as gardens, woodlots, forest, wetlands, [or] meadows.” It may have been that such natural features were cheaper, if not remotely feasible in urban school districts. It was, said Sheila Cary-Meagher, a renegade New Democrat trustee elected in the autumn of 2000 on the heels of the tear down, a lot of “icing with no cake.” Other key considerations parents ought to consider, a later progress report suggested, were whether vehicles can “safely and conveniently access the site without disrupting play? Is the playground well configured for pick up and drop off? ”

What did the Jays, the Raptors, the Leafs, and the Argos give? Zyvatkauskas learned fundraising was not “child’s play”; it was a sophisticated enterprise where everything hinged on protocol, where connections mattered more than causes, where “rich people talk to other rich people. They don’t want to talk to a mother in daycare.” The Raptors sent back a form to fill in, the Leafs offered a signed puck, and the Jays suggested an autographed baseball to auction off.

“Stop the car! Stop the car!” Ross Maceluch, aged five, shouted somewhere in West Point Grey, Vancouver, riding with his parents in March, 2002. But he could have been a kid in Brussels or Saint John, New Brunswick, or anywhere, any day since 1900. “Invariably, no matter where we go, that’s what happens,” said Ross’s mother, Janice Turner, a former Toronto resident. “A new playground—an untried playground—is better than a toy store.”

“It must be like a casino to an adult,” reflected Zyvatkauskas, who spent the early months of 2002 on the committee planning Orde Street school’s new playground. What did kids see in their playgrounds? The voices of children had been largely mute during the school playground tear down, but the Orde Street parents were determined to hear them during the rebuild. During the 2001–2002 winter, Orde Street students in different grades were asked to draw their dream playground. Working up their designs with pens, markers, and crayons, the youngsters may not have known what was good for them, but they knew what they liked: swings (especially tire swings, the most dangerous), tree houses (two, three storeys, reached with long ladders), teeter-totters (or see-saws, best used when there is subtle distrust between players), and fireman’s poles. One drawing showed a stick man walking tightrope-style on the top bar of a swing set. Another suggested a relationship between slides, height, and pleasure.

Much of what the children wanted was, to varying degrees, banned by 2002—full of “fault” in the lingo of the reports by Jeff Elliot Playground Safety Inspections, where terms such as “entrapment openings fault,” “barrier panel height fault,” “one-rung ladder handgrip fault,” and “climber access fault” comprised a specialized vocabulary. These were defined in appendices to the safety reports, but even then not so easy to interpret, which, for good or bad, led to a measure of skep-ticism. The hazards might have been there, but when did proper concern about safety become hairsplitting and overprotection? Was a thirty-six-inch-high railing that didn’t meet code really less safe than a thirty-eight-inch one that did?

In 2000, an era when only a few parents let their kids walk to school, it seemed impossible that those same caregivers—the baby-seat boomers—would refuse to get on the playground safety bandwagon, but they did. “The only logical thing to do is have lawyers to design the playgrounds,” wrote one such parent, Linwood Barclay, the Star’s humour columnist. “Here are some pieces of equipment our kids will soon be playing on,” he continued. “The Litigator Teeter-Totter: As soon as children get on the equipment, they are tied up in red tape so they won’t be thrown off….The Paralegal Bars: Similar to parallel bars from which kids can hang, but with much lower standing. Children will have to scrunch down to get under them….Contract Bridge: Before children can run across the hanging bridge that links one side of the climber to the other, they must sign a waiver….The Remand Rink: Kids won’t fall and hit their heads on the ice here. At this rink, there’s always a sign that says it’s closed…”

Anyone who did check out the accident statistics found lots of numbers, again not so easy to interpret. Health Canada’s Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program reported 4,261 playground-related injuries that required hospital visits in 1996, out of a database of 646,335 injuries of all types to all people. About half involved kids five to nine years old; most occurred between noon and 8 p.m.; more than a third were in public parks, another third in school playgrounds; June was the worst month; slides were the most common cause of injury, with nine hundred and forty-two cases, followed by monkey bars and swings; an even hundred injuries were attributed to see-saws, twenty-eight to sandboxes, ten to rocking horses. The most common injuries were fractures, bruises, cuts, and minor head injury. Just under half of the kids were sent home with no treatment or treatment requiring no follow-up. The number of fatal injuries was zero. Wente reported, “‘Some people have died on these pieces of equipment,’ an insurance official told me this summer. She couldn’t say who, or when, or how, or whether this was in Ontario.” Checking around, Wente found that “no children have died on school equipment in Ontario since 1987, the year they started keeping provincial statistics.”

Perhaps families knew instinctively that compared to injuries and deaths by automobiles and traffic, playgrounds weren’t on the map. Wasn’t this the idea behind playgrounds all along? “A quarter century ago when the movement for public playgrounds was getting underway, the playground was demanded as a haven from the physical and moral dangers of the street,” Weaver Weddel Pangburn, of the Playground and Recreation Association of America and an early commentator on the subject, wrote in the highbrow Annals of the American Academy in the late nineteen-twenties. “If it was needed then to protect child life, it is needed ten times as badly today… In New York City alone, 422 children were killed on the streets in 1926… It may be taken for granted that public playgrounds are safety zones and that they save the lives of many children each day when in operation… Instances of fatal accidents on playgrounds are rare.”

The “playground movement” Pangburn refers to was long forgotten by 2000, but had been an illustrious period in the history of education. Its seeds, arguably, go as far back as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the great French philosopher. Rousseau urged lots of free play and a measure of independence for young children. A playground was named for him in honour of his advocacy of play. The famous kindergarten system, which was developed by Friedrich Froebel in Germany, and is still very much with us, evolved around such “naturalist” ideas, which aimed to offer children a world of rich play opportunities.

But it was really municipal reform movements in the late nineteenth century that created the playground as we know it—the cliché park or schoolyard with a selection of hardware for youngsters to play on. By the mid-eighteen-nineties, so-called “reform” movements had taken root in cities across North America. In Toronto, where there were in the neighbourhood of fifty public schools by 1895, “each of these is supplied with a playground,” the columnist known as “Portia” wrote in a September 7, 1895, commentary in the Star. She voiced concerns, voiced again in Toronto more than a century later, that certain neighbourhoods got better playgrounds than others, “some large and beautifully planted with trees, as in the case of the Parkdale school, others in the heart of the city, much smaller.” Just the same, she estimated that given the average walk to a school was between five and seven minutes, “27,000 children are living within seven minutes’ walk of a playground.”

The playground movement got a boost in the mid-eighteen-nineties with the publication of How the Other Half Lives, a book about the gap in standard of living between rich and poor, written by muckraking reporter Jacob Riis, who drew attention to the need for recreation activities in cities, particularly among the children of immigrants and the poor, whose dense neighbourhoods were far from the era’s “leisure parks” where the wealthy went strolling.

Toronto was right in step—“Most of the newcomers joined Toronto’s poor in the most densely populated and squalid areas of the city,” planner Wayne Reeves wrote in the nineteen-nineties. “These new patterns created unease among Toronto’s middle class, enabling reformers to turn children’s leisure into a public issue…”

Everywhere, many of the reformers were middle- and upper-class women, who used their clout to agitate for government spending to create playgrounds in parks and school-yards. It became a powerful international movement, with its own association and periodical, The Playground. The movement drew the support, over the years, of such luminaries as U.S. president Theo-dore Roosevelt, Helen Keller, Chicago settlement worker Jane Addams, cereal magnate W. K. Kellogg, Central Park designer Frederick Law Olmsted, and, latterly, psychologist William Blatz, founder of Toronto’s St. George’s School, which became the Institute of Child Study at the University of Toronto.

In The City Beautiful Movement, a history of city planning after the eighteen-nineties, William Wilson suggested the playground movement was “explicitly controlling and manipulative,” in imposing a middle-class outlook on working-class families, basically to keep their kids from wreaking havoc. Among the movement’s more elaborate bits of propaganda was a 1910 novel, The Girl from Vermont, about a school teacher in love with playgrounds. Why? “If children are allowed to play in the streets, their first lesson is one of disobedience to municipal law,” she dutifully declares. “The storekeepers hate him, the policeman drives him on, and he takes refuge in holes and corners where vicious idling goes on.”

Despite all this social baggage, playgrounds were hugely successful. Over time, their popularity crossed all borders, classes, and barriers. In 1911, developer William Harmon gave a paper to the American Civic Association, extolling the real estate industry to give land for playgrounds out of “pure enlightened self interest,” because it boosted property values. In the nineteen-nineties, the founders of Home Depot celebrated similar values: “One of the favourite company-supported programs is KaBOOM!, through which we build playgrounds for children all over the United States,” Bernie Marcus and Arthur Blank said in their business autobiography, Built from Scratch.

Hardly anyone noticed how directly playgrounds reflected their times. How the vandal-proof, iron-pipe swing sets and climbers of the early nineteen-hundreds mirrored the classist attitudes that spawned playgrounds (“EVERWEAR STANDS FOR WEAR AND TEAR,” one equipment company declared in a 1916 advertisement; “playgrounds: ‘ALL-STEEL’ VS. ALL STEAL,” said A. G. Spalding & Bros., the sporting-goods maker, in an ad in the trade journal American City). Few saw how climbers shaped like the Gemini space capsule captured nineteen-sixties Cold War culture’s anxiety, expressing as they did the need to interest children in becoming scientists (“A real climber for small astronauts,” said the maker of one such example, the Mexico Forge Inc., of Mexico, Pennsylvania). Or how the adventure playgrounds, which were evolving by the late nineteen-sixties, expressed the crunchy-granola spirit of an era when wood felt good and experiments in open-area schools were in full swing.

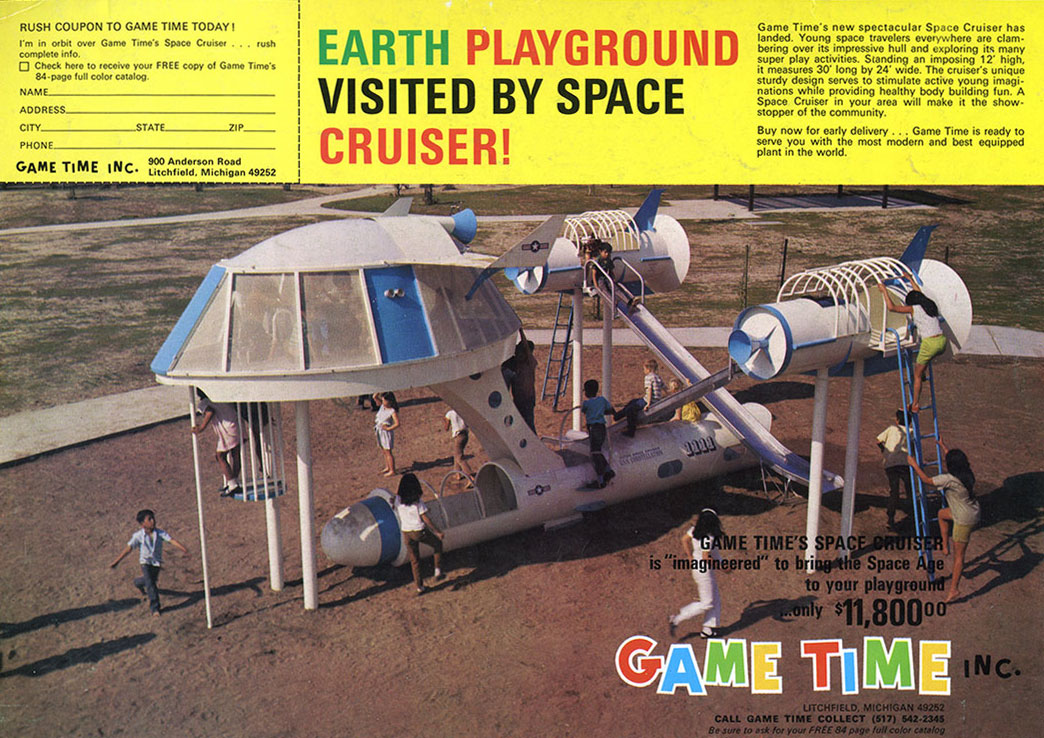

The epitome of the playground as the mirror of an era was surely reached when Cold War angst, television-based pop culture, and free spirit came together in one piece of playground equipment: the massive Space Cruiser, resembling the starship Enterprise, sold by Game Time Inc. of Litchfield, Michigan. Star Trek, starring Canadian William Shatner, had just completed its three-year run on NBC. On this massive climbing gym, kids could all but go into orbit: there was a cockpit pod youngsters could “beam” out of on something like a fireman’s pole, wing slides, and jet engines the children could climb right into. The design was shown off at the National Recreation and Park Association annual conference in September, 1970. The play gym stood “an imposing 12′ high;” it was thirty feet long and twenty-four feet wide. Imagine the lurking Klingons that Jeff Elliott, the playground inspector, would need to expunge. At warp speed he would surely consign this U.S.$11,800 spaceship to the boneyard, somewhere on a distant star.

What would the school playgrounds being re-planned after the great Toronto tear down reflect? The forces shaping them would be many and not altogether harmonious. There were parents, some resigned, some converted, yet many still bitterly skeptical of the “experts” who’d been obediently responsive to obscure insurance collectives and ignored them.

There would be the influence of the city of Toronto, Canada’s largest municipality, which in its own parks maintained an airline-style upgrading program that ensured long life for equipment while incorporating functional and safety improvements.

And there would be the Toronto District School Board itself, cash-strapped and in chaos in 2002 due to provincial education policy (“12 MORE SCHOOLS FACE SHUTDOWN,” a headline in the Star read on April 17th. “Funding falls short, board says”). Hints of apologies and acknowledgements of haste and misjudgement had appeared during the debate. “I am personally sorry for the situation we are in,” a pressured Gary Parkinson, an executive officer with the board, told one parent council in September, 2000, but “the board is still ripping out playgrounds,” it was reported the next day.

Meanwhile, dissent had grown among trustees after the fall, 2000, elections. David Moll, the trustee who had introduced the motion to tear down equipment deemed unsafe under the voluntary C.S.A. standards, was off the board. The curmudgeonly Sheila Cary-Meagher, an assertive, leftist, pro-playground former trustee, was returned in the dust of the tear down. But ultimately, most of the incumbents survived and administrators and a majority of trustees dug in their heels. Because of playground injuries, “There were lawsuits, claims against our board and other boards,” trustee Judi Codd, from suburban Willowdale, would say in 2002. “It gave us an opportunity to make some changes where there should be changes.”

So, was it a triumph of courage in the face of misinformed public censure and in defence of children’s broader interest? Or a moment of infamy when public officials chose to hide haste and misjudgement and waste by exploiting, all out of proportion, unassailable values—the safety of young citizens?

The absolute truth wasn’t clear, but telling was the fact that—Orde Street students’ drawings notwithstanding—the most absent voices from the discussion would be those of children themselves. There were surely reasons for this—techniques of public protest and cross-examination of official statements and decisions were not in the kids’ curriculum. “They’re not like the high-school kids,” said Caz Zyvatkauskas, “who can go to city hall and advocate for the [swimming] pools.”

Another reason the kids weren’t heard from might have been that, had they been able, they might have delivered a message few would have wanted to hear.

It would likely have been a profound point, about growing up and managing risk, accepting responsibility, learning independence, and exercising judgement. These were all essential life skills, but for a generation youngsters had been increasingly protected from discovering them through experience. The playground had been conceived as a place to become wise to the world—where limits could be tested in relative safety, but where nonetheless there could be consequences. It was this challenge that was playgrounds’ essential ingredient, their draw, and their method of teaching—and it was this edge that such events as the 2000 Toronto playground tear down sought to remove.

“It’s about how fast they can go, how sick they can get, and how scared they can feel,” Michelle Martindale, a teacher at the University of Toronto’s Institute for Child Studies, said about playgrounds in 1998. Her Grade 2 classroom was part of a small but real public school where the fabled institute founded by Dr. Blatz still evaluated techniques for broader application in the Canadian education system. In an informal but telling poll of students, merry-go-rounds—anecdotally the most hated piece of playground equipment in hospital emergency rooms—topped the list of most-desired bits of playground equipment.

“Do you like the danger? ” an interviewer asked pupil Shannon Curley, at the institute. “Yeah,” she said, summing up in a word the tension that underlay the tear down.

Toronto’s new school playgrounds would likely be splinter-free, plastic, rustproof, and low to the ground. Would the kids like them? Children were never too concerned with playground fashions, so perhaps. Would they learn from them? Nothing real, nothing useful, it increasingly seemed.

In this, the playground tear down might be seen as a caricature of the broader trends in education in Ontario at the millennium—the dumbing down and demolition of a once diverse, challenging, public institution in service of the safe, the dull, and the much cheaper.

But really, it was simpler than that. Toronto school children were the innocents sacrificed in a war—a war, like most, begun over misunderstanding, fed by stupidity, sustained by paranoia, and laced with incompetence.

It was a war that nobody won.